Christians Shouldn’t Be Dismissive of Scientific Modeling

Image

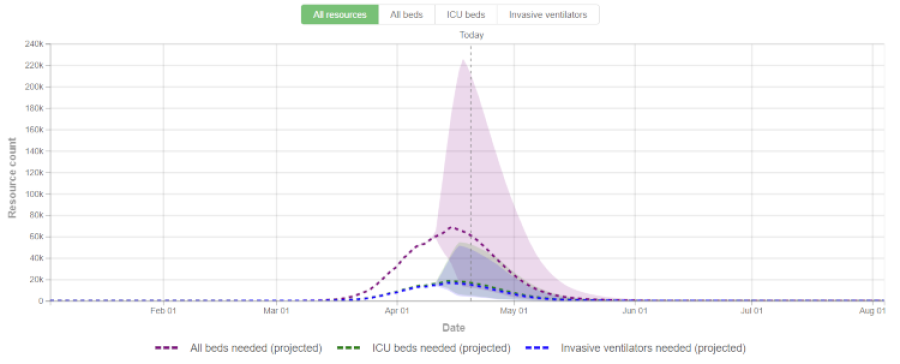

Projections from an IHME model.

Over the last several weeks I’ve encountered a range of negative views toward the models epidemiologists have been using in the struggle against COVID-19. Skepticism is a healthy thing. But rejecting models entirely isn’t skepticism. Latching onto fringe theories isn’t skepticism. Rejecting the flattening-the-curve strategy because it’s allegedly model-based isn’t skepticism either.

These responses are mostly misunderstandings of what models are and of how flattening-the-curve came to be.

I’m not claiming expertise in scientific modeling. Most of this is high school level science class stuff. But for a lot of us, high school science was a long time ago, or wasn’t very good—or we weren’t paying attention.

What do models really do?

Those tasked with explaining science to us non-scientists define and classify scientific models in a variety of ways.

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, for example, describes at least 8 varieties of models, along with a good bit of historical and philosophical background. They’ve got about 18,000 words on it.

A much simpler summary comes from the Science Learning Hub, a Science-education project in New Zealand. Helpfully, SLH doesn’t assume readers have a lot of background.

In science, a model is a representation of an idea, an object or even a process or a system that is used to describe and explain phenomena that cannot be experienced directly. Models are central to what scientists do, both in their research as well as when communicating their explanations. (Scientific Modeling)

Noteworthy here: models are primarily descriptive, not predictive. Prediction based on a model is estimating how an observed pattern probably extends into what has not been observed, whether past, present, or future.

Encyclopedia Britannica classifies models as physical, conceptual, or mathematical. It’s the mathematical models that tend to stir up the most distrust and controversy, partly because the math is way beyond most of us. We don’t know what a “parametrized Gaussian error function” is (health service utilization forecasting team, p.4; see also Gaussian, Error and Complementary Error function).

But Christians should be the last people to categorically dismiss models. Any high school science teacher trained in a Christian university can tell you why. I’ve been reminded why most recently in books by Nancy Pearcy, Alvin Plantinga, William Lane Craig, and Samuel Gregg: Whether scientists acknowledge it or not, the work of science is only possible at all because God created an orderly world in which phenomena occur according to patterns in predictable ways. For Christians, scientific study—including the use of models to better understand the created order—is study of the glory of God through what He has made (Psalm 19:1).

Most of us aren’t scientists, but that’s no excuse for scoffing at one of the best tools we have for grasping the orderliness of creation.

Should we wreck our economy based on models?

The “models vs. the economy” take on our current situation doesn’t fit reality very well. Truth? The economy is also managed using models. A few examples:

- Calculating the unemployment rate

- Unemployment forecasting (also this)

- Business forecasting

- Cost Modeling

Beyond economics, modeling is used all the time for everything from air traffic predictions to vehicle fire research, to predictive policing (no, it isn’t like “Minority Report”).

Models are used extensively in all sorts of engineering. We probably don’t even get dressed in the morning without using products that are partly the result of modeling—even predictive modeling—in the design process.

Christians should view models as tools used by countless professionals—many of whom are believers—in order to try to make life better for people. Pastors have books and word processors. Plumbers have propane torches. Engineers and scientists have models. They’re all trying to help people and fulfill their vocations.

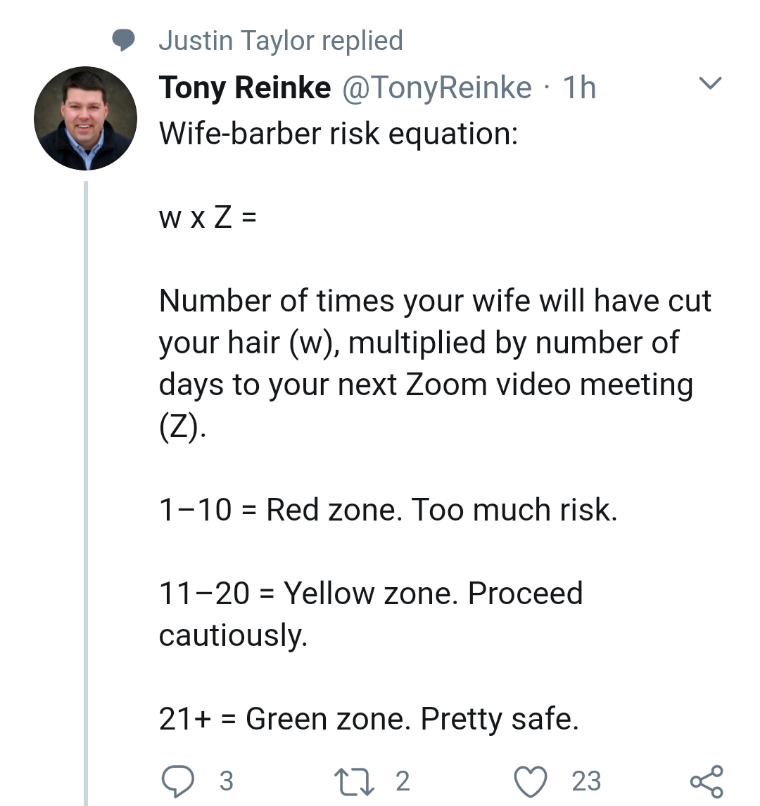

(An excellent use of predictive mathematical modeling…)

Why are models often “wrong”?

An aphorism about firearms says, “Guns don’t kill people; people kill people.” Implications aside, it’s a true statement. It’s also true that math is never wrong; people are wrong. Why? Math is just an aspect of reality. In response to mathematical reality, humans can misunderstand, miscalculate, and misuse, but reality continues to be what it is, regardless.

The fact that the area of a circle is always its radius squared times an irrational (unending) number we call “pi” (π) remains true, no matter how many times I misremember the formula, plug the wrong value in for π, botch the multiplication, or incorrectly measure the radius.

The point is that models, as complex representations of how variables relate to each other and to constants, are just math. In that sense, models are also never “wrong”—just badly executed or badly used by humans. That said, a model is usually developed for a particular purpose and can be useless or misleading for the intended purpose, so, in that sense, “wrong.”

When it comes to using models to find patterns and predict future events, much of the trouble comes from unrealistic expectations. It helps to keep these points in mind:

- Using models involves inductive reasoning: data from many individual observations is used in an effort to generalize.

- Inductive reasoning always results in probability, never certainty.

- The more data a model is fed, and the higher the quality of that data, the more probable its projections will be.

- When data is missing for parts of the model, assumptions have to be made.

- Changes in a model’s predictions are not really evidence of “failure.” As the quantity and quality of data changes, and assumptions are replaced with facts, good models change their predictions.

- True professionals, whether scientists or other kinds of analysts, know that models of complex data are only best guesses—and they don’t claim otherwise.

- The professionals that develop and use models in research are far more tentative and restrained in their conclusions than people who popularize the findings (e.g., the media).

In the case of COVID-19, one of the most influential models has been one of IHME’s (Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation). Regarding that model, an excellent Kaiser Family Foundation article notes:

Models often present “best guess” or median forecasts/projections, along with a range of uncertainty. Sometimes, these uncertainty ranges can be very large. Looking at the IHME model again, on April 13, the model projected that there would be a 1,648 deaths from COVID-19 in the U.S. on April 20, but that the number of deaths could range from 362 to 4,989.

Poor design and misuse have done some damage to modeling’s reputation. Some famous global-warming scandals come to mind. But in the “Climategate” controversy, for example, raw data itself was apparently falsified. The infamous hockey stick graph appears to have involved both manipulated raw data and misrepresentation of what the model showed. Modeling itself was not the problem.

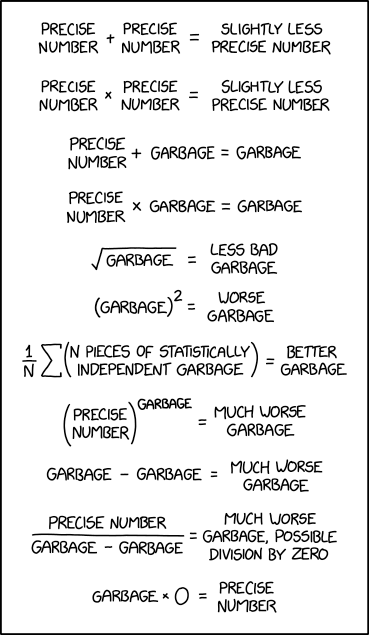

(XKD isn’t completely wrong … there is such a thing as “better garbage”)

Why bother with models?

Given the uncertainty built into predictive mathematical models, why bother to use them? Usually, the answer is “because we don’t have anything better.” Models are about providing decision-makers, who don’t have the luxury of waiting for certainty, with evidence so they don’t have to rely completely on gut instinct. It’s not evidence that stands alone. It’s not incontrovertible evidence. It’s an effort to use real-world data to detect patterns and anticipate what might happen next.

As for COVID-19, the idea that too many sick at once would overwhelm hospitals and ICUs, and that distancing can help slow the infection rate and avoid that disaster, isn’t a matter of inductive-reasoning from advanced statistical models. It’s mostly ordinary deduction (see LiveScience and U of M). If cars enter a parking lot much faster than other cars exit, you eventually get a nasty traffic jam. You don’t need a model to figure that out.

You do need one if you want to anticipate when a traffic jam will happen, how severe it might be, how long it might last, and the timing of steps that might help reduce or avoid it.

Leaders of cities, counties, states, and nations have to manage large quantities of resources and plan for future outcomes. To do that, they have to make educated guesses about what steps to take now to be ready for what might happen next week, next month, and next year. It’s models that make those guesses educated ones rather than random ones.

Highly technical work performed by exceptionally smart fellow human beings is a gift from God. Christians should recognize that. Because we’ve been blessed with these people and their abilities (and their models) COVID-19 isn’t killing us on anywhere near the scale that the Spanish Flu did in 1918 (Gottlieb is interesting on this). That’s divine mercy!

(Note to those hung up on the topic of “the mainstream media”: none of the sources I linked to here for support are “mainstream media.” Top image: IHME.)

Aaron Blumer 2016 Bio

Aaron Blumer is a Michigan native and graduate of Bob Jones University and Central Baptist Theological Seminary (Plymouth, MN). He and his family live in small-town western Wisconsin, not far from where he pastored for thirteen years. In his full time job, he is content manager for a law-enforcement digital library service. (Views expressed are the author's own and not his employer's, church's, etc.)

- 186 views

I thought the biggest risk was getting a few kids killed in the process, but whatever.

Aspiring to be a stick in the mud.

Here’s an article (from MSN, no less) claiming that the coding behind the Imperial College model was unreliable and a “buggy mess.”:

https://www.msn.com/en-gb/news/coronavirus/coding-that-led-to-lockdown-…

This is not particularly surprising to me, if true. It was pretty obvious that the predictions were so far off as to call into question either the assumptions, data, or model itself. Looks like it may be the last of those. One does not have to be a conspiracy theorist or science denier to have a healthy does of skepticism about what is being fed to us these days. Even more so when the models produced by this author in the past have also provided wildly inaccurate results.

Dave Barnhart

And then this kind of stuff happens.

Let’s stop trusting science (and models) and stick with trusting God.

https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2020/05/cdc-and-states-are-m…

Ashamed of Jesus! of that Friend On whom for heaven my hopes depend! It must not be! be this my shame, That I no more revere His name. -Joseph Grigg (1720-1768)

Fortunately for all of us, this is a completely false disjunction.

We all know God uses means, otherwise you’d have to sit down for dinner and say “let’s stop trusting silverware and stick with trusting God.” Of course, the food wouldn’t be there in the first place since, even when God provided manna, they had to use their own brains to figure out how much to gather and on what day… as well as their own muscles to do the work.

That’s how it’s always worked. God didn’t name the animals for Adam.

Yes, scientists make mistakes. In the case of the linked article at the Atlantic (wait… mainstream media; aren’t we supposed to reflexively reject everything they say?), it isn’t a failure of science. It’s a failure to actually do science. There’s nothing scientific about humans being dumb. That’s not science. It’s the opposite of science. … it’s sloppy handling of data.

Which, if it proves anything, proves we need more science at CDC. But it’s really not that either. It’s humans making bad decisions. (Most likely, it’s politics!)

Please note this: science is not special when it comes to human error.

- Referees at sporting events make errors

- Athletes make errors

- Preachers make errors in sermons

- Truck drivers make delivery errors

- Judges and juries make errors in judgments

- Politicians make decision-making errors

- Bankers and accountants make calculation errors

Do I need to list more? Well, yes, scientists also make errors.

Does the fact that all these folks make mistakes show that they’re completley useless? Should we trust God instead of truckers, preachers, judges, politicians, bankers and accountants? No, not “instead of.” We trust God quite differently.

All human trust is limited in both quality and scope. Always. I don’t trust a barber to fix my teeth. I don’t trust a banker to do surgery on me. I don’t trust a scientist to tell me the meaning of life. I don’t trust any human to be correct all the time, good all the time, wise all the time, and righteous all the time. For that, of course, there is only God who is worthy of trust. We don’t trust God or all these human beings and their work. We trust God and all these human beings and their work. The trust of God has a profoundly different quality and scope, but they do co-exist. … and we know this. We affirm it every time we tell someone, “I trust you.” It’s not idolatry.

(I hope this doesn’t sound like an angry rant. I’m not actually angry… but there are few things I am more passionate about than the unity of truth and the high calling of all the disciplines, including science…. so it does really get me going! :-) )

Views expressed are always my own and not my employer's, my church's, my family's, my neighbors', or my pets'. The house plants have authorized me to speak for them, however, and they always agree with me.

[Aaron Blumer]Fortunately for all of us, this is a completely false disjunction.

I had a feeling I’d get your dander up on this one, and it serves to prove my point that you are completely unwilling to accept that your article is an opinion piece. I’m not sure if you have some sort of skin in the game that is clouding your judgment, but it certainly appears that way.

How many times do we need to find out that really important people, really smart people, in really important positions, have made really big errors, for you to admit that we should not blindingly follow what the so-called experts are telling us? I am not saying Christians should refuse to listen to the modelers or outright dismiss them, but I am saying we should not simply accept what they say and follow their conclusions because they’re the experts and are all personally motivated by their desire to do what is best for everyone. They and all of the other scientists are wrong too often, and, in this case, they have been shown wrong many, many times. And this should not surprise us: there is no living scientist on the planet who has ever experienced anything even remotely resembling this pandemic.

–

Overall, I’m still puzzled about the post. It has practically nothing to do with Sharper Iron, unless you were just trying to generate traffic to keep the business viable. The best that SI does is in causing Christians to exercise their minds theologically. Your article is a blog post, not something worthy of being posted on SI. The post has one scripture reference - hardly the kind of thing that will sharpen our theological senses. There is one possible unintended consequence: to help Christians understand that it is okay for each of us to have a different perspective, and we all need to love one another despite our differing opinions. Today, as pastors across the country are trying to figure out how to re-open their churches, they are faced with a multitude of opinions from their members, and they still need to make decisions knowing some will not only mildly disagree but even vehemently disagree. But if I can encourage you in one way, it is in calling you out on your insistence that your way, according to the article, is the only way, is the right way, and those who disagree are clearly wrong. This is not Christian love, it is pride. You are demanding other Christians to agree with your opinion, and you create division and strife among brothers in doing so. I have loved many of your posts over the years and have shared them with many others. I respect your opinion on this post, but your insistence on its right-ness is wrong.

Ashamed of Jesus! of that Friend On whom for heaven my hopes depend! It must not be! be this my shame, That I no more revere His name. -Joseph Grigg (1720-1768)

Discussion