Christians Shouldn’t Be Dismissive of Scientific Modeling

Image

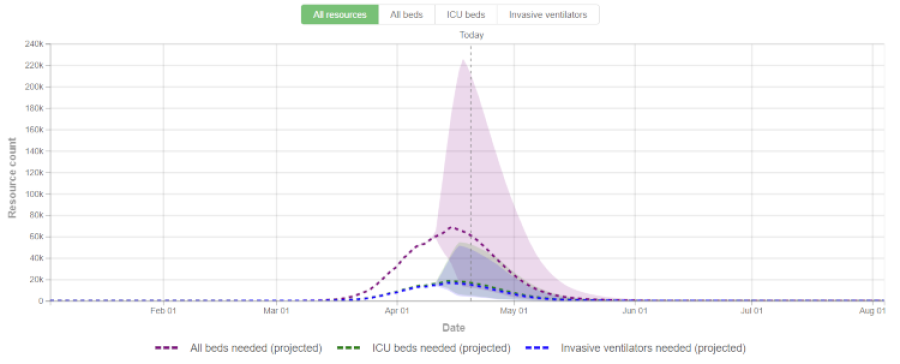

Projections from an IHME model.

Over the last several weeks I’ve encountered a range of negative views toward the models epidemiologists have been using in the struggle against COVID-19. Skepticism is a healthy thing. But rejecting models entirely isn’t skepticism. Latching onto fringe theories isn’t skepticism. Rejecting the flattening-the-curve strategy because it’s allegedly model-based isn’t skepticism either.

These responses are mostly misunderstandings of what models are and of how flattening-the-curve came to be.

I’m not claiming expertise in scientific modeling. Most of this is high school level science class stuff. But for a lot of us, high school science was a long time ago, or wasn’t very good—or we weren’t paying attention.

What do models really do?

Those tasked with explaining science to us non-scientists define and classify scientific models in a variety of ways.

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, for example, describes at least 8 varieties of models, along with a good bit of historical and philosophical background. They’ve got about 18,000 words on it.

A much simpler summary comes from the Science Learning Hub, a Science-education project in New Zealand. Helpfully, SLH doesn’t assume readers have a lot of background.

In science, a model is a representation of an idea, an object or even a process or a system that is used to describe and explain phenomena that cannot be experienced directly. Models are central to what scientists do, both in their research as well as when communicating their explanations. (Scientific Modeling)

Noteworthy here: models are primarily descriptive, not predictive. Prediction based on a model is estimating how an observed pattern probably extends into what has not been observed, whether past, present, or future.

Encyclopedia Britannica classifies models as physical, conceptual, or mathematical. It’s the mathematical models that tend to stir up the most distrust and controversy, partly because the math is way beyond most of us. We don’t know what a “parametrized Gaussian error function” is (health service utilization forecasting team, p.4; see also Gaussian, Error and Complementary Error function).

But Christians should be the last people to categorically dismiss models. Any high school science teacher trained in a Christian university can tell you why. I’ve been reminded why most recently in books by Nancy Pearcy, Alvin Plantinga, William Lane Craig, and Samuel Gregg: Whether scientists acknowledge it or not, the work of science is only possible at all because God created an orderly world in which phenomena occur according to patterns in predictable ways. For Christians, scientific study—including the use of models to better understand the created order—is study of the glory of God through what He has made (Psalm 19:1).

Most of us aren’t scientists, but that’s no excuse for scoffing at one of the best tools we have for grasping the orderliness of creation.

Should we wreck our economy based on models?

The “models vs. the economy” take on our current situation doesn’t fit reality very well. Truth? The economy is also managed using models. A few examples:

- Calculating the unemployment rate

- Unemployment forecasting (also this)

- Business forecasting

- Cost Modeling

Beyond economics, modeling is used all the time for everything from air traffic predictions to vehicle fire research, to predictive policing (no, it isn’t like “Minority Report”).

Models are used extensively in all sorts of engineering. We probably don’t even get dressed in the morning without using products that are partly the result of modeling—even predictive modeling—in the design process.

Christians should view models as tools used by countless professionals—many of whom are believers—in order to try to make life better for people. Pastors have books and word processors. Plumbers have propane torches. Engineers and scientists have models. They’re all trying to help people and fulfill their vocations.

(An excellent use of predictive mathematical modeling…)

Why are models often “wrong”?

An aphorism about firearms says, “Guns don’t kill people; people kill people.” Implications aside, it’s a true statement. It’s also true that math is never wrong; people are wrong. Why? Math is just an aspect of reality. In response to mathematical reality, humans can misunderstand, miscalculate, and misuse, but reality continues to be what it is, regardless.

The fact that the area of a circle is always its radius squared times an irrational (unending) number we call “pi” (π) remains true, no matter how many times I misremember the formula, plug the wrong value in for π, botch the multiplication, or incorrectly measure the radius.

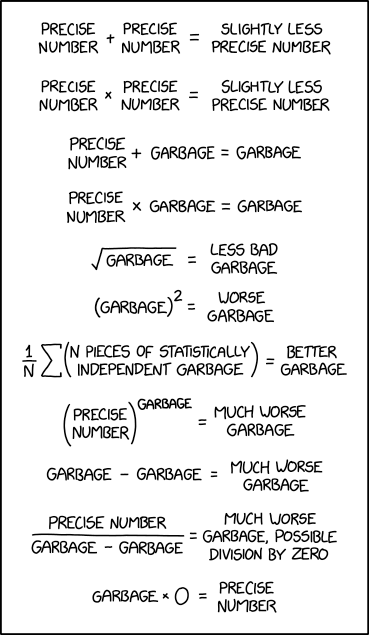

The point is that models, as complex representations of how variables relate to each other and to constants, are just math. In that sense, models are also never “wrong”—just badly executed or badly used by humans. That said, a model is usually developed for a particular purpose and can be useless or misleading for the intended purpose, so, in that sense, “wrong.”

When it comes to using models to find patterns and predict future events, much of the trouble comes from unrealistic expectations. It helps to keep these points in mind:

- Using models involves inductive reasoning: data from many individual observations is used in an effort to generalize.

- Inductive reasoning always results in probability, never certainty.

- The more data a model is fed, and the higher the quality of that data, the more probable its projections will be.

- When data is missing for parts of the model, assumptions have to be made.

- Changes in a model’s predictions are not really evidence of “failure.” As the quantity and quality of data changes, and assumptions are replaced with facts, good models change their predictions.

- True professionals, whether scientists or other kinds of analysts, know that models of complex data are only best guesses—and they don’t claim otherwise.

- The professionals that develop and use models in research are far more tentative and restrained in their conclusions than people who popularize the findings (e.g., the media).

In the case of COVID-19, one of the most influential models has been one of IHME’s (Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation). Regarding that model, an excellent Kaiser Family Foundation article notes:

Models often present “best guess” or median forecasts/projections, along with a range of uncertainty. Sometimes, these uncertainty ranges can be very large. Looking at the IHME model again, on April 13, the model projected that there would be a 1,648 deaths from COVID-19 in the U.S. on April 20, but that the number of deaths could range from 362 to 4,989.

Poor design and misuse have done some damage to modeling’s reputation. Some famous global-warming scandals come to mind. But in the “Climategate” controversy, for example, raw data itself was apparently falsified. The infamous hockey stick graph appears to have involved both manipulated raw data and misrepresentation of what the model showed. Modeling itself was not the problem.

(XKD isn’t completely wrong … there is such a thing as “better garbage”)

Why bother with models?

Given the uncertainty built into predictive mathematical models, why bother to use them? Usually, the answer is “because we don’t have anything better.” Models are about providing decision-makers, who don’t have the luxury of waiting for certainty, with evidence so they don’t have to rely completely on gut instinct. It’s not evidence that stands alone. It’s not incontrovertible evidence. It’s an effort to use real-world data to detect patterns and anticipate what might happen next.

As for COVID-19, the idea that too many sick at once would overwhelm hospitals and ICUs, and that distancing can help slow the infection rate and avoid that disaster, isn’t a matter of inductive-reasoning from advanced statistical models. It’s mostly ordinary deduction (see LiveScience and U of M). If cars enter a parking lot much faster than other cars exit, you eventually get a nasty traffic jam. You don’t need a model to figure that out.

You do need one if you want to anticipate when a traffic jam will happen, how severe it might be, how long it might last, and the timing of steps that might help reduce or avoid it.

Leaders of cities, counties, states, and nations have to manage large quantities of resources and plan for future outcomes. To do that, they have to make educated guesses about what steps to take now to be ready for what might happen next week, next month, and next year. It’s models that make those guesses educated ones rather than random ones.

Highly technical work performed by exceptionally smart fellow human beings is a gift from God. Christians should recognize that. Because we’ve been blessed with these people and their abilities (and their models) COVID-19 isn’t killing us on anywhere near the scale that the Spanish Flu did in 1918 (Gottlieb is interesting on this). That’s divine mercy!

(Note to those hung up on the topic of “the mainstream media”: none of the sources I linked to here for support are “mainstream media.” Top image: IHME.)

Aaron Blumer 2016 Bio

Aaron Blumer is a Michigan native and graduate of Bob Jones University and Central Baptist Theological Seminary (Plymouth, MN). He and his family live in small-town western Wisconsin, not far from where he pastored for thirteen years. In his full time job, he is content manager for a law-enforcement digital library service. (Views expressed are the author's own and not his employer's, church's, etc.)

- 186 views

I never suggested any conspiracy. My question was about power and the limits of seeking it. The bottom line is that we all know that people will go to great lengths to get power and will stop at almost nothing on the road there. That doesn’t require a conspiracy theory. It simply requires understanding people, power, and politics.

However, as I said elsewhere, perhaps the great conspiracy theory is that so many people believe that there are no conspiracies. The idea that people in power won’t use public policy and the power of office is a idea so silly it is hard to imagine anyone believes it. That’s not to say that’s true of all people in public office. It is surely true of some.

We can safely say that there have been enough bad decisions made during this time that might not reasonably be attributed to good will or even stupidity. Sometimes, the easiest and most apparent answer is the actual answer.

[Larry]I never suggested any conspiracy. My question was about power and the limits of seeking it. The bottom line is that we all know that people will go to great lengths to get power and will stop at almost nothing on the road there. That doesn’t require a conspiracy theory. It simply requires understanding people, power, and politics.

However, as I said elsewhere, perhaps the great conspiracy theory is that so many people believe that there are no conspiracies. The idea that people in power won’t use public policy and the power of office is a idea so silly it is hard to imagine anyone believes it. That’s not to say that’s true of all people in public office. It is surely true of some.

We can safely say that there have been enough bad decisions made during this time that might not reasonably be attributed to good will or even stupidity. Sometimes, the easiest and most apparent answer is the actual answer.

Who said there are no conspiracies? Who is saying that people won’t use public policy and office to stay in power? What I am saying, and I believe some others would agree, is that the type of thing that is being suggested is too grand, too difficult to pull off, and beyond the scope of being reasonable. I had a friend who was a truther. The arguments he used were eerily similar: People in power will do anything to stay there, there are some who would even kill for more power, “they” are all working together, etc. Personally, I don’t have any more hope for the GOP than I do the Democrat party although I do appreciate their pro-life stance. I think when it starts to be suggested that the GOP is the pro-God party (!) and the Democrats will stop at nothing, including destroying the economy, to attack God’s people (the GOP) through the misuse of modeling (which may have also been nefariously constructed) we are in conspiracy territory. You may not be saying that Larry but many are.

Josh, I think you are having a conversation I am not having.

A video called “PlanDemic” makes the case that people in high places are involved in a conspiracy concerning this present virus crisis. If you choose to watch this video, use your own critical thinking skills to decide for yourself what to make of it.

That video, and others like, are peddling in the paranoid stupidity too many Christians fall for. Please stop.

Tyler is a pastor in Olympia, WA and works in State government.

[RajeshG]If you choose to watch the video PlanDemic, you should also carefully and thoroughly scrutinize this critique of it that seeks to rebut it:A video called “PlanDemic” makes the case that people in high places are involved in a conspiracy concerning this present virus crisis. If you choose to watch this video, use your own critical thinking skills to decide for yourself what to make of it.

The anti-vaxx agenda of The Plandemic

My point is pretty simple as I stated earlier: people can be so desperate for power that they will engage in certain behaviors to increase the chances of gaining that power, even if those behaviors are significantly damaging to others. Those who ignore that as a possible reason for things are ignoring a rather obvious reason.

I don’t know “the type of thing being suggested” that you referring to and I haven’t heard anyone say that the GOP is God’s Own People aside from those joking about it. So I may well agree with you about that. My point is bigger.

[Larry]My point is pretty simple as I stated earlier: people can be so desperate for power that they will engage in certain behaviors to increase the chances of gaining that power, even if those behaviors are significantly damaging to others. Those who ignore that as a possible reason for things are ignoring a rather obvious reason.

I don’t know “the type of thing being suggested” that you referring to and I haven’t heard anyone say that the GOP is God’s Own People aside from those joking about it. So I may well agree with you about that. My point is bigger.

Some in this thread have suggested that this is all an anti-God agenda from unbelieving scientists and Democrats. I certainly agree with the bolded section and I think everyone here does. I really don’t think anyone here is disagreeing with that. Just wondering what exactly you think that includes in this situation. Maybe I’m misunderstanding you brother but it seems like you are rebutting by asking the question. In which case I am simply wondering how you see that working in this situation.

My take: Many Christians have a crazy gene. I see this in my own church

Aaron,

I wonder if you might consider responding to people individually rather than en masse. It makes it appear that you are responding to one person and it’s confusing. IMO, it would be better to split it out so as not to appear to attribute views or positions to people who don’t hold them and to make it easier to follow.

I also wonder if there is any level of evidence or argument that you would accept that perhaps you are missing something and that there is another legitimate side of the argument. You have talked about those who don’t understand models. Where did you get your expertise? I understand what you are saying but I wondering why we should trust you over all the people who are saying differently? What do you say to all the experts with the degrees and reputation who disagree with you?

On to a few specifics of your response to me.

These sentences don’t go together. If a model is fed poor data and the projections don’t turn to “come true,” there is no defect in the model. This is a data problem.

You said “These sentences don’t go together,” then said the exact same thing I said, and then you proceed to say, “Please learn about how models work.” I don’t understand what you mean. Why don’t the sentences go together and what do I need to learn that you apparently also need to learn?

In any case, as I’ve already explained, predictive models project a range of possibilities with varying levels of probability. They don’t say “this will happen” or “this will not happen.” There are always lots of “ifs” and “probablys” and “possiblys.”

Of course. I think we all know this.

If a model’s predictions to do not change significantly as assumptions are replaced with facts and data improves, that would be evidence of a defective model. For this kind of data—an unfolding pandemic that we knew zero about at the beginning—predictions staying the same = bad model. I don’t know how to make it any simpler.

Yes, and I think this is the point that many are making. The question here is whether or not the right data is being used and whether it is being rightly used. There appear to be reasons to doubt both.

This is not correct and I’ve already explained why and how. Feel free to reread. I don’t have anything new to say about that.

I am not sure what is not correct here. I have read all you have said here. Are you saying it is wrong to suggest that we need not to attribute ill intent or motive? Or that it is wrong to consider? I can’t imagine you are saying that it is not correct to say that models are to give reasonable depictions of things. Nobody thinks models are perfect. But nobody should think that models are completely open-ended. The depiction that models give is intended to be reasonable., isn’t it? Does anyone really dispute that?

What good is a model that says the rain totals in the Midwest US this summer will be between 2 inches and 49,000,000 inches? Is that helpful to anyone for anything? I would say think it needs no argument to say that models need to be reasonable depictions of things.

My take: Many Christians have a crazy gene. I see this in my own church

That’s hardly a Christian thing.

[TylerR]I was referring to people who believe all Democrats, particularly Democratic Governors, are each engaged in a united effort to destroy this country so they can impose socialist control. Conspiracy theories and general irresponsibility appear to be endemic on the right, particular the Religious Right. I’m not sure why.

As someone who has worked in government my entire life, I can safely say this - government cannot pull off a massive conspiracy! Yet, the simplistic statements (“they’re trying to take control,” etc.) we see everywhere by irresponsible fools on the Right make it clear that some of these people are simply not rational human beings. Their followers who parrot their lines and share their YouTube videos are being irresponsible.

“Don’t let a good crisis go to waste,” indeed! Many people in the Religious Right Industrial Complex are taking that to heart, and are whipping up gullible people (including too many Christians) into a frenzy of foolishness.

The pastor I mentioned, above, who called for civil disobedience was Jeff Durbin. His sermon has now been watched over 30,000 times on Facebook.

Yeah, I thought about watching Durbin’s message the other day, but I couldn’t bring myself to care enough about what he had to say. :-)

Thanks for sharing the gist of it and sparing me an hour.

As someone who has worked in government my entire life, I can safely say this - government cannot pull off a massive conspiracy!

As you say this, there is a lot of evidence coming out about the Russia investigation and particularly the situation with Michael Flynn. One might reasonably differ on the import of this and whether or not it can be called a conspiracy, but the idea that there was a lot going on behind the scenes that was supposed to stay behind the scenes is indisputable.

The pastor I mentioned, above, who called for civil disobedience

I haven’t watched this sermon and have no intention of doing so, but at what point would you call for civil disobedience regarding the assembling of the church?

[Mark_Smith]like chem-trails or tin foil hats or illuminati and lizard men.

I am shocked you would compare reasonable objections to how models are being used to that.

Mark, we’ve been seeing plenty of the same kind of irrationality… Including gaslighting: where someone quotes a (still unaddressed) rational argument I’ve made and accuses me of desperation… all while completely missing (or choosing to ignore) my actual point. This is what people do when they don’t really have a rational counterargument… when they’re dedicated to a position that is not based on facts and reasoning. … lots of strawmanning, distraction to irrelevant topics, quoting out of context.

If people are going to abandon reason, they might as well reach for the foil hats. Why not?

For my part, the abundance of sheer nuttiness I’m seeing and hearing from people I have long thought were mature and rational humans has been pretty close to overwhelming lately. I’ve had to do some serious reflecting on how I’m going to live with it. How to be at peace and not be robbed of joy. I’ve come to some conclusions.

- This is an intense time and some normally rational people are going to tip over for a while. It happens to all of us under the right (wrong?) conditions. Lots of folks are going to come to their senses on their own over the coming months when they get their equilibrium back (it might be a lot of months).

- What is, is. If I’m going to be intellectually lonelier going forward, then I am. Time to accept it and go from there.

- When you bump into something repeatedly, it’s easy to leap to the conclusion that “it’s everywhere!” But more objective measurements are pretty clear that most Americans are concerned about both the economy and going back to work too soon; most believe the disease is deadly serious and the overall response we’ve taken in the U.S. (the same as that of the entire world) has been the best one we could, with the information we have; and an increasing number of evangelicals are no longer impressed with Trump (this may seem like changing the subject, but it really is related, at a deeper “thinking style” level).

- I’m not the sort of person to ignore off-the-wall thinking in my own circles, but I can’t respond to everything and can’t straighten everybody out and shouldn’t try. Nobody should try. So… the challenge is balance. There’s a new nutty story on Facebook every couple of hours. And there’s a new batty Tweet from someone I used to look up to a couple of times a week. So I have to learn to take a deep breath and walk away from most of these, if I can’t avoid seeing them at all. … then occasionally select something more widespread to confront in some way.

- I think there are deeper problems that fuel all this, and probably those who care about the Christian mind should focus on these deeper theological and philosophical issues… populism, obscurantism, anti-intellectualism, anti-scientism, and lots of gaps in biblical anthropology along with emotional stuff. There’s plenty of it. Always has been, I’m sure. None of this is new, it’s just that the times have exposed more of it than usual all at once.

- It’s important to remember that every human is a mixed bag. Almost nobody is completely lacking in redeeming qualities (not “redeeming” in the soterological sense). We’re all uneven, so that guy I used to respect who is now spreading absurd nonsense all over Facebook and Twitter still has his redeeming qualities, though they’re a lot harder to see right now. I don’t want to be guilty of the same kind of binary thinking I’m trying to fight: the sort that classes everybody as Us or Them based on the shibboleth of the moment.

Views expressed are always my own and not my employer's, my church's, my family's, my neighbors', or my pets'. The house plants have authorized me to speak for them, however, and they always agree with me.

Discussion