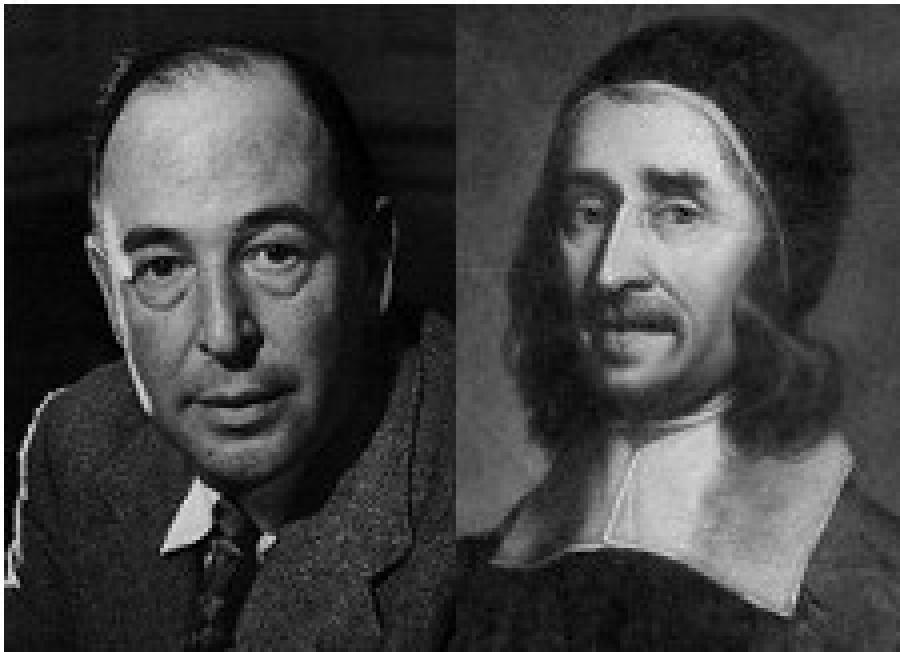

Mere Christianity: An Examination of the Concept in Richard Baxter & C. S. Lewis (Part 3)

Image

From Detroit Baptist Seminary Journal (DBSJ), with permission. Read Part 1 and Part 2.

C. S. Lewis and Mere Christianity

N. H. Keeble, speaking about the connection between Baxter and Lewis, wrote, “[There is] a pervasive coincidence of idea and emphasis between the work of the most popular and influential Christian evangelist and apologist of the seventeenth century and that of his counterpart in the twentieth.”1 Indeed, a similarity of thought should be expected, since Lewis borrowed a central phrase from Baxter’s thought. But we will also find that there are some striking differences. This section will develop Lewis’s conception of MC. The reader is encouraged to look for the subtle differences in thought between the two great Christian thinkers. The next section will make the differences as well as the commonalities explicit, allowing us to examine how the Christian apologist should incorporate MC into his defense of the faith.

Lewis’s Historical Situation

Lewis’s life was spent in a post-Christian Europe ravaged and demystified by two world wars. Many of the remnants of Christianity remained throughout the European world; however, the substance of Christianity had faded at least a generation before. As a result, Christianity was coming under attack on two fronts. First, many were seeking to abolish religion in light of the “modern advances.” Science was offered as an explanation for everything, including the origin of life through Darwin’s theory of evolution. Second, Scripture was being understood as a work of historical fiction to be handled by the sociologists. The consequence was the humanizing of Scripture, which allowed man to control biblical revelation. Both of these challenges—modernism and liberalism—were substantial in Lewis’s day and became significant obstacles to Christian belief in the European world.2

Faced with such unbelief, Lewis determined that the age-old battle between Catholics and Protestants was distracting to the Christian cause. Both groups should have a united front to face what Lewis believed was the greater challenge of unbelief.3 The essentials of Christianity, Lewis believed, were shared between Catholics and Protestants, and while their disagreements were significant, they paled in light of the unity provided by the essential theological beliefs they shared. In the preface to Mere Christianity, Lewis writes that the agreements between Christians—including Catholics and Protestants—“turns out to be something not only positive but pungent; divided from all non-Christian beliefs by a chasm to which the worst divisions inside Christendom are not really comparable at all.”4

Lewis and Ecumenical Spirit

Why did Lewis present MC as opposed to his own denominational stance as an Anglican? Lewis gives three reasons in the Introduction to Mere Christianity.5 First, Lewis believed that only the experts should speak to matters of deep theology. As a layman, he believed he ought not trespass into the dangerous territory of theological argumentation.6

Lying behind this statement was Lewis’s personal belief that the Christian gospel was simple and easily understood by the common man. Second, Lewis believed that more talented (and theologically astute) writers were devoting their time to controversial theological truths. In sum, to write an apologetic treatise for the Anglican Church would have been fruitless since he was not as qualified as other writers, and it would not have filled a needed void. Instead, Lewis believed he ought to write to the simple man about the simple Christian message. Lewis felt adequate in that field, since any believer is qualified to speak on the essentials of Christianity. He felt further justified in that there appeared to be a void in this field: “That part of the line where I thought I could serve best was also the part that seemed to be the thinnest. And to it I naturally went.”7

Another substantial reason Lewis gave in Mere Christianity for writing on MC rather than Anglicanism concerns the need of unregenerate men. Lewis believed that arguing over theological peculiarities hindered unbelievers from accepting the truth of the Christian gospel: “I think we must admit that the discussion of these disputed points has no tendency at all to bring an outsider into the Christian fold. So long as we write and talk about them we are much more likely to deter him from entering any Christian communion than to draw him into our own.”8 The great unity of the Christian faith, Lewis believed, was a substantial argument for its validity. Yet the argumentation Lewis found in most religious books spoke past unbelievers to established Christians. Consequently, the message communicated to unbelievers betrayed an internal war within the Christian camp. For this reason, Lewis sought to fill the gap. He wanted to write to the exponentially growing post-Christian world about the validity of the Christian message. In order to do this, Lewis felt it was imperative to shed the husk and teach the core.

A final reason Lewis chose to write on MC can be gathered from his other works. Namely, Lewis’s apologetic ideology was grounded in his belief that there was much more that united Christians than divided them. In 1933, nineteen years before the publication of Mere Christianity, Lewis was asked to enter a debate on the merits of Anglicanism and Catholicism. Lewis responded, “When all is said…about the divisions of Christendom, there remains, by God’s mercy, an enormous common ground.”9 Thus, when Mere Christianity was originally published, the content was the product of mature reflection on denominational differences.10

The apologetic value of a unified Christian witness was personal to Lewis. Even before he was a Christian, Lewis was impressed with the unity of Christianity:

When I still hated Christianity, I learned to recognize like some all too familiar smell, that almost unvarying something which met me, now in Puritan Bunyan, now in Anglican Hooker, now in Thomist Dante. It was there…in Francois de Sales;…in Spenser and Walton;…in Pascal and Johnson…in the urban sobriety of the eighteenth century one was not safe—Law and Butler were two lions in the path…. It was, of course, varied; and yet—after all—so unmistakably the same; recognizable, not to be evaded, the odour which is death to us until we allow it to become life…. We are all rightly distressed and ashamed also, at the divisions of Christendom. But those who have always lived within the Christian fold may be too easily dispirited by them. They are bad, but such people do not know what it looks like from without. Seen from there, what is left intact despite all the divisions, still appears (as it truly is) an immensely formidable unity. I know, for I saw it; and well our enemies know it.11

Thus, Lewis believed that the unity of the Christian faith—despite what it may look like from the believer’s viewpoint—is a strong argument for the validity of the Christian message. If Christians were intent on living this reality, Lewis was convinced that Christian apologetics would be greatly advanced.

In summary, Lewis’s reasons for writing on MC are evangelistic and apologetic in principle. No doubt he also wanted to bring healing to the divided church, but his overriding purpose was to present Christ in simplicity to his post-Christian generation.12

Notes

1 Keeble, “C. S. Lewis, Richard Baxter,” 27.

2 N. H. Keeble notes the striking continuity between the two great Christian apologists: “Each man was confronted by a significant break with the Christian tradition of the past and a consequent weakening of the authority and influence of the church. Baxter had to face the divisiveness and contentiousness consequent upon England’s protracted and uncertain Reformation, Lewis the disillusion and apostasy which followed the two world wars” (ibid., 28).

3 Michael H. Macdonald and Mark P. Shea, “Saving Sinners and Reconciling Churches,” in The Pilgrim’s Guide: C. S. Lewis and the Art of Witness, ed. David Mills (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1998), 47–48.

4 Lewis, Mere Christianity, xi.

5 Ibid., viii-ix.

6 “I am a very ordinary layman of the church of England, not especially ‘high,’ nor especially ‘low,’ nor especially anything else” (ibid., viii).

7 Ibid., ix.

8 Ibid., viii.

9 Walter Hooper, C. S. Lewis: A Companion & Guide (San Francisco: Harper, 1996), 295–96.

10 Actually, it was first broadcast as a radio publication, then later developed into a book.

11 C. S. Lewis, “Introduction,” in St. Athanasius: The Incarnation of the Word of God (Bedford, NY: Fig Press, 2012), 4.

12 Lewis, Mere Christianity, ix. Ibid.

Tim Miller Bio

Dr. Tim Miller is Assistant Professor of Systematic Theology and Apologetics at Detroit Baptist Theological Seminary. He received his M.A. from Maranatha Baptist University, his M.Div. from Calvary Baptist Theological Seminary, and his Ph.D. in historical theology from Westminster Theological Seminary.

- 16 views

Discussion