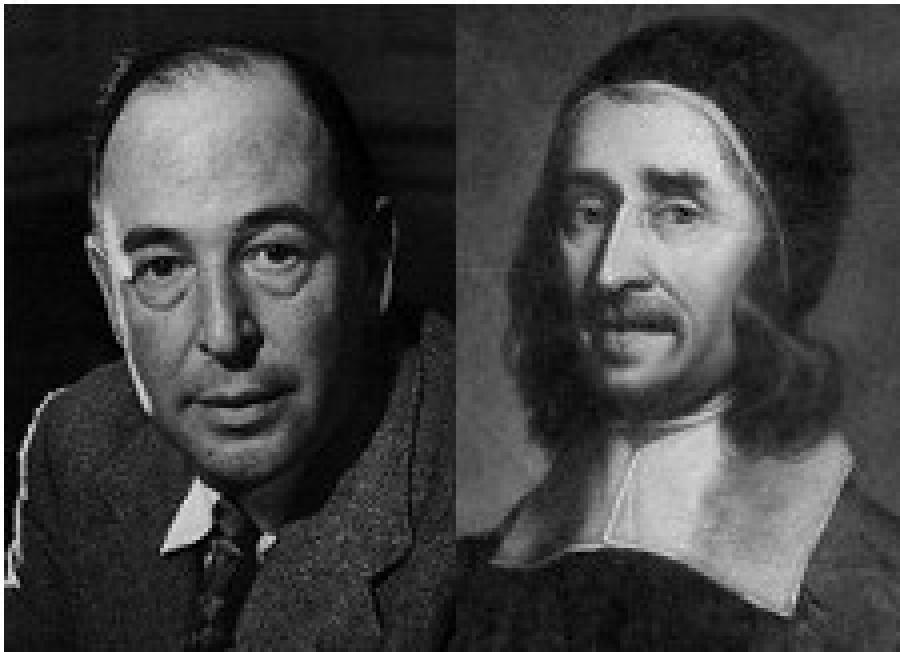

Mere Christianity: An Examination of the Concept in Richard Baxter & C. S. Lewis (Part 6)

Image

From Detroit Baptist Seminary Journal (DBSJ), with permission. Read the entire series.

Essential Beliefs of Mere Christians

Neither Baxter nor Lewis was as explicit as he could have been concerning the content of MC. However, we saw that Baxter was much more thorough than Lewis. What is immediately obvious is that both Lewis and Baxter speak highly of tradition. As they look into the tomes of church history they find a continuity of belief and doctrine from the apostles to their own day. They believe that Christ passed the truth to his people and the truth was never lost to the ages. Thus, they share a common conviction of the holistic unity of the church. Both men also gave Scripture priority over tradition. In sum, Baxter and Lewis essentially have much the same criteria for determining the content of MC.

But if this is the case, then why is there such a discrepancy of belief concerning the Roman Catholic Church? Lewis has sometimes been hailed as a defender of Roman Catholic doctrine. For instance, Peter Milward notes, “Not a few Catholics, on reading his books about Christianity, have formed the impression that there was no difference in doctrine between him and themselves.”1 On the other hand, Catholics lament the fact that Lewis chose to use a term from Baxter, an anti-Catholic Puritan.2 Why, if they held to similar beliefs about MC did they differ so greatly on the matter of the Roman Catholic Church?

Perhaps Baxter was merely a product of his own time and circumstances. He was born in anti-papal England only a few generations after the great tumult with Rome. But the same argument can be turned against Lewis. Could it be that Lewis was also a product of his time and circumstances? Many of his close associates were Roman Catholic, including many in the Inkling literature group.3 Further, many would say that the denominational characteristics of the Anglican Church mirrored closely that of the Roman Catholic Church, so that Lewis might have been blinded to the real differences between the two religious establishments.

Overall, the difference between the men should not be explained solely in terms of environment. Instead, it will be argued that Baxter’s final requirement of a Mere Christian—undiluting addition—makes the significant difference. Again, that requirement argued that extra beliefs one holds should not bring the essential beliefs into question. Baxter argued for the invalidity of Roman Catholicism this way:

Since faction and tyranny, pride and covetousness, became the matters of the religion of too many, vice and selfish interest hath commanded them to change the rule of faith by their additions, and to make so much necessary to salvation, as is necessary to their affected universal dominion, and to their carnal ends…. He is the true catholic Christian that hath but one, even the Christian religion: and this is the case of the Protestants, who, casting off the additions of popery, adhere to the primitive simplicity and unity: if Papists, or any others, corrupt this religion with human additions and innovations, the great danger of these corruptions is, lest they draw them from the sound belief and serious practice of that ancient Christianity which we are all agreed in…. For he that truly believes all things that are essential to Christianity, and lives accordingly with serious diligence, hath the promise of salvation: and it is certain, that whatever error that man holds, it is either not inconsistent with true Christianity, or not practically, but notionally held, and so not inconsistent as held by him: for how can that be inconsistent which actually doth consist with it?4

Thus, the problem with Roman Catholicism is not that they did not hold to the doctrines of Christ, grace, or any number of other Christian beliefs; their problem is that their additions to Christianity bring the foundations into question. For this reason, Baxter believed that Roman Catholics could be true believers only in spite of Rome and not because of Rome.5

A second factor that divided Baxter and Lewis on the merits of the Roman Catholic Church concerned the priority of tradition to revelation. Baxter said of Scripture, “We take the Word of God for the Rule of our Faith, and the Law of the Church, sufficiently determining of all that is Standing, Universal Necessity or Duty, in order to Salvation.”6 Baxter’s overriding concern for the teaching of Scripture is evident in his distaste for creeds. He spoke of the “vanity, yea the sinfulness of men’s undertaking to determine by canons what God thought not fit to determine in his Laws.”7 While Lewis would have agreed with Baxter concerning the priority of Scripture,8 Lewis seems to have a greater and deeper concern for tradition than Baxter. Joseph Pearce, a Roman Catholic, recognized that Lewis’s “conception of ‘mere Christianity’ was far more ‘Catholic,’ in its sacramentalism and in its defence of ecclesiastical tradition, than would be tolerable to the typical Presbyterian or low-church Calvinist.”9

Overall, it appears that Lewis was not willing to critically evaluate the theology of Roman Catholicism. No doubt, Lewis’s relationships with those in the Roman Catholic Church partly explain this phenomenon. Further, the commonalities between Catholicism and an evangelical protestant Christianity are replete, and Lewis’s appreciation for the argument from the unity of the faith may have prevented him from seeing the implications of Roman Catholic doctrine for the historic Christian faith.10 Essentially, however, the problem is much deeper than these previous two points. Lewis failed to recognize the chasm between those whose primary trust is in tradition and those whose primary trust is in Scripture. Since he believed the chasm to be only a minor fault line,11 Lewis proposed that Catholics and Protestants could join together and fight the common enemy of unbelief. He underestimated the potential that Roman Catholic doctrine could itself be a form of unbelief.

Lewis’s failure to present a harmony between Catholics and Evangelicals is not only evident from the Evangelical side. Roman Catholic writers have likewise noted that his attempt was faulty:

It is … a little ironic that [Lewis’s] ‘mere Christianity’ intended as a via media or centre ground of traditional Christianity, is embraced by two such diverse theological traditions [i.e. Catholics and Evangelical Protestants]. It is clear that Protestants have to reach beyond their own beliefs if they are to embrace fully the beliefs of Lewis … . Catholics, on the other hand, are faced with the absence in Lewis’s ‘mere Christianity’ of certain doctrines that are central to the faith as taught by the Church. In other words, for a faithful Catholic, Lewis’s ‘mere Christianity’ is deficient; it is less Christian than the Church.12

Joseph Pearce recognizes in Lewis’s MC that, in seeking middle ground, Lewis has abandoned his only ground. In the end, one must choose which is primary—tradition or Scripture. The Roman Catholic Church for its part has chosen tradition. The Evangelical Church has chosen Scripture. There is no middle ground. Baxter saw this, but Lewis appears to have missed it.

Mere Christianity and Christian Apologetics

We can be thankful for the gospel work of the two Christian apologists C. S. Lewis and Richard Baxter. And the best we can do for their memory is to learn from their work, and if possible, improve on it. In that light, Lewis and Baxter provide for us a few lessons about the intersection of MC and Christian apologetics.

First, modern apologists should emphasize the unity of the gospel in Christ. Both Baxter and Lewis recognized unity as a powerful argument for Christianity, and they recognized disunity as a potential argument against Christianity. If we are to emphasize unity, those who seek to advance the gospel of Christ in our generation need to be able to clearly distinguish the doctrinal essentials that divide those within God’s flock from those who remain outside the flock. Because there will be unregenerate members within orthodox congregations, it is not possible to definitively know the elect from the non-elect. Here it is merely suggested that the apologist should know the theological boundaries of Christian orthodoxy.13

The second lesson we can learn is uniquely drawn from Lewis. He argued that Christian denominationalism will not be extinguished this side of eternity. Members of God’s church must not remain in the welcoming hallway; instead, they must move to a room. The rooms are where doctrinal commitments are made and where fellowship centered on a shared understanding of God and his Word resides. Of course, the key is to recognize which rooms are attached to the welcoming hallway. Only those rooms that share the commonality of the gospel as presented in the Word of God have a right to the hall.

Third, in order to provide solid theological boundaries, a more robust delineation of the qualifications of a Mere Christian is required. This lesson is Baxter’s unique contribution to MC and Christian apologetics. Lewis is faulted for finding too much commonality where the differences were significant. Baxter, due to his focus on the Word of God as the primary authority, was able to establish a more specific standard.14 Further, Baxter’s principle of undiluting addition is exceedingly important. If one’s doctrine brings the essential elements of the Christian message into question, his belief in the essentials must be questioned. The advantage of this principle for Christian apologetics is manifest, for if the standard of belief is firmly established, then the enemy of unbelief can be recognized—whatever form it takes.

Baxter’s contribution provides us with a tension, however. While there are clear boundaries for orthodox Christianity, there are not clear boundaries for discerning what additional beliefs dilute or do not dilute the foundational beliefs. That is, how do we determine whether an additional belief brings the foundational beliefs into question? For instance, does belief in one’s entrance into the covenant community by pedobaptism challenge the gospel of grace? Does the doctrine of baptismal regeneration serve as a dilution to the doctrine of conversion, a central aspect of the gospel?15 Does belief in dispensationalism embrace multiple paths to salvation, challenging the uniqueness of Christ?16 Does openness to modern prophetic utterance challenge the finished Scriptures and therefore the basis of the fundamental Christian doctrines?17 Lewis never saw this tension because he did not fully consider the role of additional beliefs. Baxter never sought to solve the dilemma. Instead, while he declared Roman Catholic doctrine as a dilution of the essentials of the Christian message, he did not present an exhaustive method on how one could determine whether a belief dilutes the essential beliefs.

Where does this leave us? Both Lewis and Baxter argued that the existence of the common hall is a powerful apologetic argument for Christianity. But Lewis has shown us that because of important differences, the hallway cannot be the church. And Baxter showed us that we must be careful to discern who is actually in the common hall. Ultimately, Lewis and Baxter agreed that there is a common hall, but they did not agree with who was in the common hall. This ultimately shows the difficulty of the concept of MC. Many agree that there is such a thing as MC, but not all agree concerning the content of the concept. Can we move forward towards a fully defined MC? If two thousand years of church history has failed to reach a consensus, there may be little hope this side of eternity.

In conclusion, with the historical background we have just established let us look more broadly at the intersection of MC and Christian apologetics. There are two reasons to question how much MC can aid Christian apologetics. First, as noted above, Christians disagree about the content of MC. If we are to hinge our apologetic on defending this concept, we must have a more secure definition of what it includes and what it excludes. Our second concern is more foundational. The ultimate goal of the apologist is not merely the communication of the essentials; it must also include discipleship (Matt 28:18–20).18 The danger of Lewis’s approach is that those who hear only the essentials may subsequently embrace positions that bring those essentials into question.19 Further, Jesus charged his disciples to teach all things not only the basic things. Lewis noted his own apologetic goal in Mere Christianity: “If I can bring anyone into the hall I have done what I attempted.” Nevertheless, Lewis maintains, “it is in the rooms, not in the hall, that there are fires and chairs and meals.”20 But if so, the goal of the apologist-disciple should be to bring the unbeliever both into the hall and into the right room.

Notes

1 Peter Milward, A Challenge to C. S. Lewis (Madison-Teaneck, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1995), 60.

2 Ibid.

3 J. R. R. Tolkien, Robert Havard, James Dundas-Grant, George Sayer, Gervase Mathew, and Christopher Tolkien were all part of the Inklings and were Roman Catholic. See Pearce, C. S. Lewis and the Catholic Church, 68, 132.

4 West, “Richard Baxter and the Origin of ‘Mere Christianity,’” emphasis added.

5 Baxter believed there were at least two ways a Christian could also be a Roman Catholic. First, he begrudgingly held the outward appearance, while his heart and mind held to true Christianity. Second, he could also hold Roman Catholic beliefs but not in his heart. Baxter calls this a notionally held belief. In either case, the Roman Catholic was no longer a Roman Catholic. See Richard Baxter, A Christian Directory, Or, A Body of Practical Divinity and Cases of Conscience: Christian Politics (or Duties to Our Rulers and Neighbours) (London: Richard Edwards, 1825), 263–65.

6 Quoted in Keeble, Richard Baxter, 25.

7 Ibid.

8 While it is beyond the scope of this paper to examine Lewis’s view of divine revelation, it is important to note that Lewis did not hold to a classically orthodox understanding of Scripture. The role this played in his overall view of MC is fascinating, but cannot be investigated here. For more information on his view of Scripture see, Philip Ryken, “Inerrancy and the Patron Saint of Evangelicalism: C. S. Lewis on Holy Scripture,” in The Romantic Rationalist: God, Life, and Imagination in the Work of C. S. Lewis, ed. John Piper and David Mahtis (Wheaton: Crossway, 2014), 39–64.

9 Pearce, C. S. Lewis and the Catholic Church, 63.

10 For instance, see his introduction to the French translation of The Problem of Pain in Hooper, C. S. Lewis, 296–97.

11 Lewis suggested that his fifteen-minute time limitation (on air radio presentation) was the only reason he could not present MC in a way that every Christian (including Protestants and Catholics) would agree to (see ibid., 306).

12 Pearce, C. S. Lewis and the Catholic Church, 168.

13 While some elect may be involved in non-orthodox religious groups (e.g., Baxter’s example of nominal Roman Catholic believers), they should be excluded from consideration of the breadth of orthodox Christian unity. This is because their inclusion would blur the boundaries for those with whom the Christian engages apologetically.

14 Much more needs to be said about the qualifications of a MC. However, Baxter’s dependence on Scripture as the basis of MC is undoubtedly the place to start. To develop the qualifications more thoroughly is beyond the scope of this paper.

15 See D. Patrick Ramsey, “Baptismal Regeneration and the Westminster Confession of Faith,” Confessional Presbyterian 4 (January 1, 2008): 183–91, an article dealing with the theology of the Westminster Confession of Faith and baptismal regeneration. The author suggests that while some hold to baptismal regeneration on the basis of the confession, the theology of the document does not support it.

16 While dispensationalists have consistently refuted this claim, it continues to be offered as a critique. For instance, in a 2012 interview, Sinclair Ferguson mentioned, “There are dispensationalists who seem to believe that God has operated with different ways of salvation throughout biblical history” (“Theology Night with Sinclair Ferguson & R. C. Sproul,” 20 February 2012, accessed 21 March 2015, http://www.ligonier.org/learn/conferences/ligonier_webcast_archive/jan_2…).

17 Bruce Compton, “The Continuation of New Testament Prophecy and a Closed Canon: A Critique of Wayne Grudem’s Two Levels of New Testament Prophecy” (presented at the 64th meeting of the Evangelical Theological Society, Baltimore, 2013).

18 While apologetics is designed to remove obstacles from the unbeliever hearing the gospel, the ultimate aim is conversion to Christian discipleship. Scripture provides no unique role to an apologist who merely converts people to a watered-down message. Instead, an apologist may intentionally train in the skill of removing those barriers, but this does not relieve him or her from the Great Commission obligation to disciple and teach all things God has communicated through his Word.

19 For example, Mormons and Jehovah Witnesses claim to have the same hallway, and it is imperative that unbelievers be steered away from these sects.

20 Lewis, Mere Christianity, xv.

Tim Miller Bio

Dr. Tim Miller is Assistant Professor of Systematic Theology and Apologetics at Detroit Baptist Theological Seminary. He received his M.A. from Maranatha Baptist University, his M.Div. from Calvary Baptist Theological Seminary, and his Ph.D. in historical theology from Westminster Theological Seminary.

- 43 views

Discussion