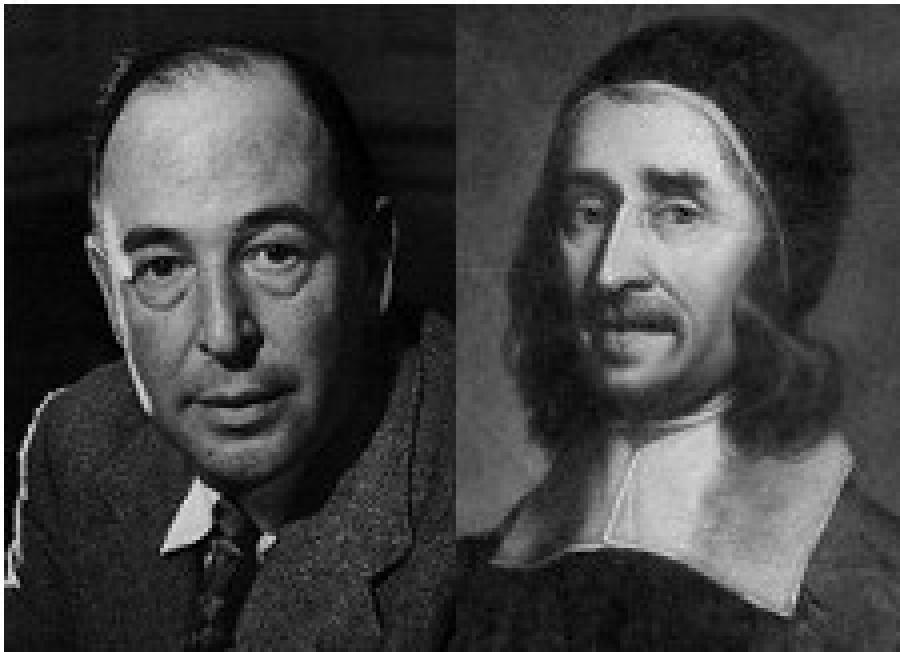

Mere Christianity: An Examination of the Concept in Richard Baxter & C. S. Lewis (Part 1)

Image

From Detroit Baptist Seminary Journal (DBSJ), with permission.

By Timothy E. Miller1

Introduction

C. S. Lewis has been hailed as one of the most influential Christians of the twentieth century. A great measure of his success was due to his appeal to large segments of the “Christian” religious community. Duncan Sprague commented on this phenomenon: “I am amazed the extreme positions within Christendom that claim Lewis as [their] champion and defender…liberals and the fundamentalists; the Roman Catholics and the evangelical Protestants…the most conservative Baptists to the most charismatic Pentecostals claiming Lewis as one of their own.”2 This led Walter Hooper, a prominent Lewis scholar, to brand Lewis as an “Everyman’s apologist.”3

A major portion of Lewis’s wide appeal should be attributed to his concept of Mere Christianity. When engaged in apologetics, Lewis believed he ought to avoid controversial issues that divided Christians.4 Instead, only the core of Christian doctrine should be advanced and defended to unbelievers. Consequently, since most of Lewis’s doctrinal comments are contained in apologetic works, it comes as no surprise that many—even strongly opposed movements—could claim him as their own.

Examining the spiritual heritage of Lewis’s works one would be led to believe that Mere Christianity (MC)5 was a huge success. Even today, Lewis’s works are being reprinted for and sold to an ever-increasing public. However, even successes have failures. The point of this paper, then, is to critically examine Lewis’s conception of MC, asking what the content of such a concept may be and whether it is ultimately helpful.

In order to fulfill our task, we will examine the historical foundations of Lewis’s concept. Namely, we will trace MC back to its origin in Richard Baxter. Having considered Baxter’s view of MC, we will compare it to Lewis’s conception. Finally, we will seek to show where Lewis and Baxter’s conceptions of MC were different and how a proper understanding of these differences should modify our understanding of the connection between MC and Christian apologetics.

Richard Baxter & Mere Christianity

Though popular opinion may ascribe the expression Mere Christianity to Lewis, the term dates back hundreds of years before Lewis to Richard Baxter, a seventeenth-century Puritan, who coined the phrase. Unfortunately, Baxter’s name is not well known in the modern world. In his day, however, Baxter was a prolific author, writing over 160 works.6 Samuel Johnson, a distinguished English author in his own right, answered a question as to which of Baxter’s works should be read by saying, “Read any of them; they are all good.”7 As a professor of English literature, it comes as no surprise that Lewis was familiar with Baxter’s work. The extent to which Lewis was familiar with Baxter must, unfortunately, remain uncertain. Nevertheless, it is clear that the concept of MC derives from Baxter.8 But did Lewis intend to further develop Baxter’s view of MC? Or did Lewis commandeer the term, empty it of Baxter’s meaning, and fill it with his own meaning? An examination of Baxter’s use of the term will lead us to embrace the latter position.9

Baxter’s Historical Context

In order to fully understand Baxter’s use of MC, we must understand the historical circumstances in which he lived. Religious rivalry was the norm of life throughout England during Baxter’s lifetime (1615–1691). Henry VIII’s break with Rome was only the beginning of the religious strife that would mark the country for many generations. As Baxter’s ministry matured, the religious battles were no longer being fought with the continent; rather, the battles were internal to England. The political lines were drawn alongside the religious lines. Due to the dictates of his conscience, Baxter found himself fighting with the Nonconformists under Cromwell. When the monarchy was re-established, Baxter was appointed to the royal chaplaincy.10 But, due to the Act of Uniformity (1662), his position was short lived.11 The act demanded that all pastors exclusively use the Book of Common Prayer and be ordained by the Anglican Church. Baxter was neither willing nor conscientiously able to obey the act.

Did Baxter leave his post because he was a Presbyterian? Some have claimed as much, but Baxter’s beliefs remained more elusive than a denominational name could identify.12 N. H. Keeble notes, “Baxter has proved an elusive figure. Modern scholars claim him both as Puritan and Anglican; as representative of the central moderate Puritan tradition and as its ‘stormy petrel’; as a rationalist and a mystic; as a Calvinist and an Arminian; as a fully integrated personality and as an ‘utterly self-divided man.’”13 When pressed to determine his religious affiliation Baxter wrote:

I am a CHRISTIAN, a MEER CHRISTIAN, of no other Religion; and the Church that I am of is the Christian Church…. I am against all Sects and dividing Parties: But if any will call Meer Christians by the name of a Party, because they take up with Meer Christianity, Creed, and Scripture, and will not be of any dividing or contentious Sect, I am of that Party which is so against Parties: If the Name CHRISTIAN be not enough, call me a CATHOLICK CHRISTIAN; not as that word signifieth an hereticating majority of Bishops, but as it signifieth one that hath no Religion, but that which by Christ and the Apostles was left to the Catholick Church, or the Body of Jesus Christ on Earth.14

Describing himself at a different time, Baxter said, “You could not (except a Catholick Christian) have trulier called me than a Episcopal-Presbyterian Independent.”15 Since the main options for Baxter at that point (save for Catholicism) were Presbyterianism, Anglicanism, and independence, Baxter identified himself with, paradoxically, all of them and none of them. He wanted to identify with none, but at the same time, he did not want to exclude any.

Baxter’s omni/non-position exasperated his opponents. Some of his contemporaries began calling his unique blend of Christianity Baxterianism—of which he despaired.16 He wanted no identifying adjective placed next to Christian. He did not want to be a Catholic, Presbyterian, Anglican, Independent, or any other Christian; he wanted to be a Christian. The adjective mere was not to become another faction within the church. In fact, the word mere was designed to indicate the lack of an adjective, not the replacement for an adjective.

Notes

1 Dr. Miller is Assistant Professor of Systematic Theology and Bible Exposition at Detroit Baptist Theological Seminary in Allen Park, MI.

2 Duncan Sprague, “The Unfundamental C. S. Lewis,” Mars Hill Review (1995): 53–63.

3 From an interview reported in Joseph Pearce, C. S. Lewis and the Catholic Church (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2003), 131.

4 C. S. Lewis, Mere Christianity (San Francisco: HarperCollins, 2001), ix.

5 MC will stand for the idea while Mere Christianity will be reserved for the title of the work by Lewis.

6 John G. West, “Richard Baxter and the Origin of ‘Mere Christianity,’” Discovery Institute, last modified 1996, accessed 29 July 2015, http://www.discovery.org/a/460.

7 Quoted in ibid.

8 Lewis cites Baxter as the source of the concept, but Lewis does not develop the connection between his use of the term and Baxter’s use of the term (Lewis, Mere Christianity, ix).

9 Of course, in light of what was said above, it is possible that Lewis misunderstood Baxter’s position. It is more likely, however, that Lewis embraced some elements of Baxter’s MC and appropriated other aspects on the basis of his own historical context.

10 Pearce, C. S. Lewis and the Catholic Church, 118.

11 Pearce doubts the depth of Baxter’s ecumenism because Baxter did not support the Act of Uniformity, which was designed to bring unity among Christians. How can Baxter pursue ecumenism and yet work against an act that would bring unity? The answer lies in Baxter’s strong position on the role of religious conscience. Baxter desired a church united without coercion. Since the Act of Uniformity demanded all preachers become Anglicans to preach, Baxter was obliged to leave his post. This was not in spite of Baxter’s ecumenism, but because of his ecumenism (ibid.).

12 See N. H. Keeble, “C. S. Lewis, Richard Baxter, and ‘Mere Christianity,’” Christianity and Literature 30 (1981): 10, 28.

13 N. H. Keeble, Richard Baxter, Puritan Man of Letters (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1982), 22.

14 Richard Baxter, Church-history of the Government of Bishops and their Councils (London: John Kidgell, 1680), xv, accessed 29 July 2015, https://archive.org/details/ churchhistoryofg00baxt.

15 Quoted in Keeble, “C. S. Lewis, Richard Baxter,” 29.

16 Keeble, Richard Baxter, 23.

Tim Miller Bio

Dr. Tim Miller is Assistant Professor of Systematic Theology and Apologetics at Detroit Baptist Theological Seminary. He received his M.A. from Maranatha Baptist University, his M.Div. from Calvary Baptist Theological Seminary, and his Ph.D. in historical theology from Westminster Theological Seminary.

- 209 views

I recently read Lewis’ The Great Divorce. I picked it up at a library paperback rack for $0.25. I need to read it again. I have serious questions about Lewis’ views on eternity after reading it. It was interesting, but kind of … weird, too.

Tyler is a pastor in Olympia, WA and works in State government.

Tyler,

Good to hear from you, friend.

Lewis fans would defend him on this point, indicating that he suggests the work is fictional. Nevertheless, it does seem to go in the direction of the trajectory of some of his other comments on hell. So even if it is fictional, it seems to represent the broad idea of what Lewis thought Hell would be like.

Discussion