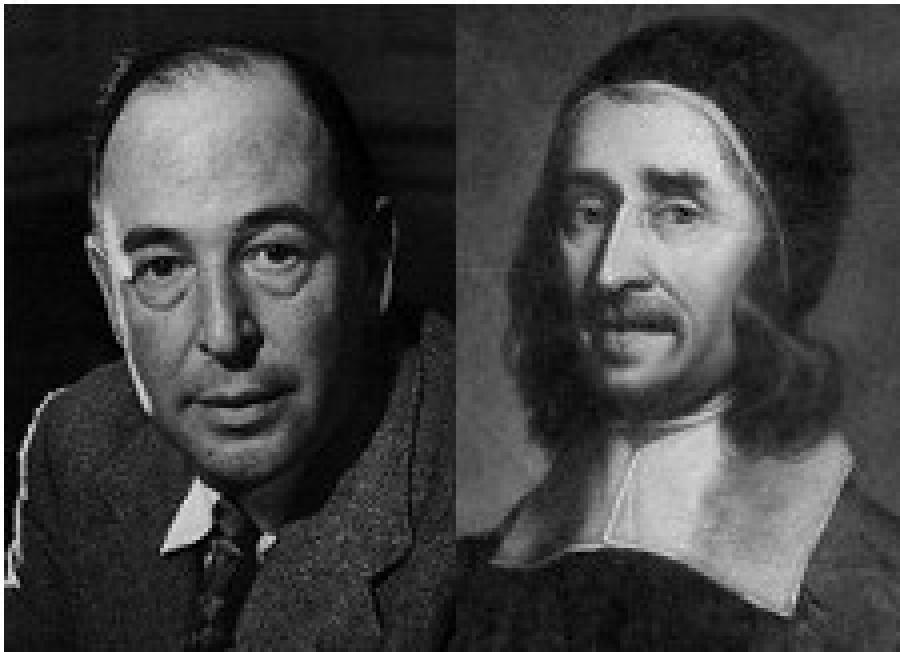

Mere Christianity: An Examination of the Concept in Richard Baxter & C. S. Lewis (Part 4)

Image

From Detroit Baptist Seminary Journal (DBSJ), with permission. This section continues to examine Lewis’ concept of mere Christianity. Read the series so far.

Lewis’s Conception of a Mere Christian

Nowhere in Mere Christianity does Lewis elucidate the fundamentals of a Mere Christian. In various places he gives hints of what may be included. For instance, he says that doctrinal differences should never be expressed in the presence of those who have not yet “come to believe that there is one God and that Jesus Christ is His only Son.”1 So we have at least two explicit essentials: first, Mere Christians are Monotheists, and second, they believe Jesus Christ is God’s Son.2 In another place, Lewis gives a second, more mystical definition: “It is at [the church’s] centre that each communion is really closest to every other in spirit, if not in doctrine. And this suggests that at the centre of each there is a something, or a Someone, who against all divergences of belief … speaks with the same voice.”3 How can one identify a MC congregation or denomination? They have the same spirit. Here, Lewis is suggesting that Mere Christians can recognize one another by an invisible and undeniable unity of spirit.

A much clearer picture of Lewis’s conception of MC comes from a speech Lewis gave on apologetics to Anglican priests and youth leaders. In that context, Lewis provided a two-dimensional definition, describing what it is and what it is not. Positively, a Mere Christian holds to “The faith preached by the Apostles, attested by the Martyrs, embodied in the Creeds, expounded by the Fathers.”4 Negatively, “[MC] must be clearly distinguished from the whole of what any one of us may think about God and man.”5 As for the negative definition, Lewis sought to divide what was commonly held from that which individuals believed. A Mere Christian necessarily held the beliefs necessary to MC, but they might also hold additional beliefs beyond the core of MC.

Developing the positive definition is more difficult. Lewis says that MC is contained in the faith preached by the apostles, but how can we access that preaching? The context does not say. His second source is the attestation of the martyrs; however he never speaks of which martyrs. “Embodied in the creeds” is likewise unhelpful since Lewis does not specify of which creeds he speaks. And finally, he gives no indication of which fathers are to be referenced.

Being fair to Lewis, it must be admitted that he was not seeking to be explicit in a delineation of MC in this context. And many of the people he was speaking to would have had common assumptions concerning which fathers, creeds, and martyrs he was referencing. However, it is certainly distressing that Lewis never (at least to my knowledge) explicitly stated what he believed constituted MC. This lack of clarity led Steven Mueller to conclude, “It may be simply that each reader has his or her own definition of MC through which he or she evaluates Lewis’s words.”6 Certainly Lewis never intended this result, but without being explicit could Lewis have avoided it?

While none of Lewis’s public works exhibit any sort of clarity about the content of MC, one personal letter does shed some limited light on how Lewis thought about the subject. In 1945, an Anglican layman, H. Lyman Stebbins, wrote to Lewis concerning the merits of Roman Catholicism. Apparently Stebbins had been presented with information that was compelling him to accept Roman Catholicism, so he wrote to Lewis asking for guidance. Lewis wrote back and said,

My position about the Churches can best be made plain by an imaginary example. Suppose I want to find out the correct interpretation of Plato’s teaching. What I am most confident in accepting is that interpretation which is common to all the Platonists down all the centuries: What Aristotle and the Renaissance scholars and Paul Elmer More agree on I take to be true Platonism. Any purely modern views which claim to have discovered for the first time what Plato meant, and say that everyone from Aristotle down has misunderstood him, I reject out of hand. But there is something else I would also reject. If there were an ancient Platonic Society still existing at Athens and claiming to be the exclusive trustees of Plato’s meaning, I should approach them with great respect. But if I found that their teaching was in many ways curiously unlike his actual text and unlike what ancient interpreters said, and in some cases could not be traced back to within 1,000 years of his time, I should reject their exclusive claims—while ready, of course, to take any particular thing they taught on its merits.7

In this imaginary example, Lewis indicates that he believes MC lies precisely in the doctrines that have been held by all Christians throughout all times. For this reason, theological novelty should be rejected. Further, and of incredible importance, Lewis believes one should examine beliefs in light of the text they claimed to follow. In this way, Lewis was indicating the importance of Scripture. If a group called itself Christian but their theology failed to accord with the Scriptures, Lewis would not allow their errant formulations into the criteria for MC.

In summary, it is evident that Lewis’s concept of MC relies heavily upon commonly shared beliefs among those who call themselves Christian. Lewis was impressed with the continuity of Christian belief through the centuries. As such, he believed these common beliefs were the bedrock of Christianity, or put otherwise, they were the core of MC. However, since Lewis was never quite clear about the requirements of MC, one is lost in speculation as to which groups are included and which are not. Unfortunately, both heresies and truth have been held for centuries. Does heresy perpetuated become a part of those truths inherent to MC? Is the mysterious unity of the Spirit clear enough to wall off faulty doctrine? What place should be given to exegetical concerns in light of historical doctrine and the mysterious work of the Spirit? These questions remain unanswered by Lewis.

Unfortunately, Lewis’s conception of MC must remain somewhat enigmatic. But perhaps that is the way he planned to leave it. He did not want to outline the role of tradition and Scripture in exact detail, for in doing so he would have flared up the sources of division. Lewis stated, “You cannot . . conclude from my silence on disputed points, either that I think them important or that I think them unimportant. For this is itself one of the disputed points. One of the things Christians are disagreed about is the importance of their disagreements.”8 Maybe Lewis avoided giving the exact details of the content of MC, since it would have caused division and rivalry—the very things he was seeking to overcome.

Lewis & Denominations

Lewis believed that any split of the body of Christ was against God’s will: “Divisions between Christians are a sin and a scandal, and Christians ought at all times to be making contributions towards reunion, if it is only by their prayers.”9 And though Lewis believed unity was the ultimate goal “as a logician,” Lewis would say, “I realize that when two churches affirm opposing positions, these cannot be reconciled.”10 So what should be done? Lewis believed that churches ought to work together in concord on those issues in which they agree. Thus, Christians of all sorts should join arms in fighting unbelief. In Mere Christianity he noted his wish that his text might be a sort of bridge connecting the isolated islands of Christianity.11 However grandiose the intentions, Lewis remained realistic in his assessment of the possibility of complete unity. Reunion was his hope and he sought to build bridges for its possible occurrence; however he could not conceive of how it could be accomplished.12 Macdonald and Shea summarize Lewis’s position succinctly: “He believed that the key for each Christian was to go to the heart of his own communion while simultaneously locking arms with other Christians to fight the real enemy of unbelief. Analogously, during World War II, the various Allies united to fight a common enemy. Yet the French remained the French and the English remained English.”13

Despite his misgivings about denominationalism, Lewis still sought to direct converts to various denominational local assemblies. His famous illustration is that of a hallway with many doors. The hallway represents MC and its essential tenets. The rooms branching from the hallway represent different denominations. Lewis maintained, “If I can bring anyone into the hall I have done what I attempted. But it is in the rooms, not in the hall, that there are fires and chairs and meals. The hall is a place to wait in, a place from which to try the various doors, not a place to live in.”14 Lewis never sought to establish a hallway church. Mere Christianity was not designed to establish a new community of saints united in Spirit and divided in doctrine.

How exactly does one determine which room (denomination) is right for him? Lewis believes the answer is that one must pray for direction and visit the rooms (i.e., the churches) until the Lord confirms his direction. As a test case, Susie listens to the broadcasts on BBC and is convinced of the truth. She determines to follow the Lord, so she prays that the Lord would lead her to the right church. Lewis warns that Susie should not pick the one with the nicest padded chairs or the one with the most expensive sound equipment. Susie should not ask, “Do I like that kind of service,” but she should ask “Are these doctrines true: Is there holiness there? Does my conscience move me towards this? Is my reluctance to knock at this door due to my pride, or my mere taste, or my personal dislike of this particular door-keeper?”15 Evidently, Lewis was not concerned with which denomination his readers (and listeners) joined. His concern was only that they entered through the main hall into one of the rooms.

Lewis’s carefree attitude towards denominational choice was grounded in his belief that denominations were groups of Mere Christians with additional beliefs. In the letter to H. Lyman Stebbins, Lewis stated, “In one sense, there is no such thing as Anglicanism.”16 Lewis’s basis for this startling admission is that men “are committed to believing … whatever can be proved from Scripture.”17 Since many different denominations share the one Scripture, and each seeks to expound its teachings, Lewis assumed that they were unified even as they were divided. One can speak of Anglicanism, Catholicism, and Protestantism but he must keep in mind that he is speaking of a unified entity at the same time he is speaking of the diversity. For this reason, Lewis is unconcerned which particular communion a believer chooses. In the conclusion to his letter to Stebbins, who was seeking arguments in favor of Anglicanism over Catholicism, Lewis states, “Whichever you decide, good wishes.”18 This statement may shock most Christians in the age of denominationalism; however, Lewis believed the unity of the Christian message surpassed the diversity found in its various expressions.

Notes

1 Ibid.

2 And though it is only implicit, Lewis appears to suggest that one must also believe that Jesus, as the Son of God, is God incarnate.

3 Lewis, Mere Christianity, xii.

4 This quotation does not come from Mere Christianity, nor does it mention the word mere; nevertheless, Lewis’s statement comes in a context where he is encouraging church leaders to defend the Christian faith. In that context, he tells them not to defend their peculiar beliefs, but to defend historic Christianity. In Mere Christianity he is following the advice he gave to these church leaders (C. S. Lewis, God in the Dock: Essays on Theology and Ethics Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1970], 90).

5 Ibid.

6 Steven P. Mueller, “Beyond Mere Christianity,” Christian Research Journal 27 (2004), accessed 29 July 2015, http://www.equip.org/articles/beyond-mere-christianity.

7 H. Lyman Stebbins, “Correspondence with C. S. Lewis,” Catholics Education Resource Center, last modified 1998, accessed 29 July 2015, http://www.catholiceducation.org/en/religion-and-philosophy/apologetics/…stebbins.html.

8 Lewis, Mere Christianity, xii.

9 Lewis, God in the Dock, 60.

10 Translated from the French introduction to the Problem of Pain in Hooper’s text (Hooper, C. S. Lewis, 296).

11 Lewis, Mere Christianity, xi.

12 Will Vaus, Mere Theology: A Guide to the Thought of C. S. Lewis (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2004), 171.

13 Macdonald and Shea, “Saving Sinners and Reconciling Churches,” 50.

14 Lewis, Mere Christianity, xv.

15 Ibid., xvi.

16 Stebbins, “Correspondence with C. S. Lewis.”

17 Ibid.

18 Ibid.

Tim Miller Bio

Dr. Tim Miller is Assistant Professor of Systematic Theology and Apologetics at Detroit Baptist Theological Seminary. He received his M.A. from Maranatha Baptist University, his M.Div. from Calvary Baptist Theological Seminary, and his Ph.D. in historical theology from Westminster Theological Seminary.

- 15 views

Discussion