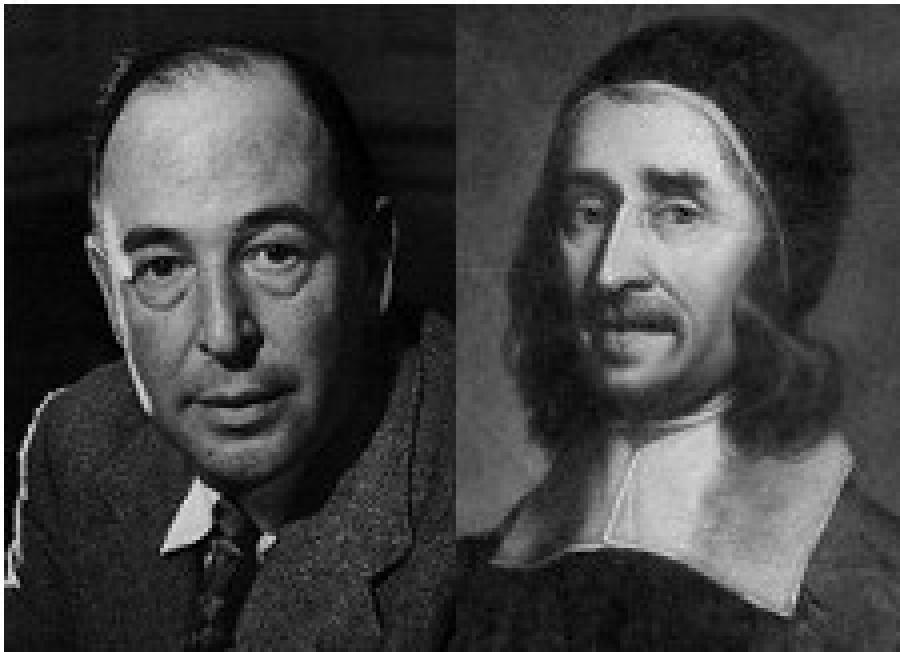

Mere Christianity: An Examination of the Concept in Richard Baxter & C. S. Lewis (Part 5)

Image

From Detroit Baptist Seminary Journal (DBSJ), with permission. Read the series so far.

Baxter Vs. Lewis

In seeking to find the relation between MC and Christian apologetics, we have noted two great historical figures. Both men were successful in their respective ages in spreading the gospel of Jesus Christ. However, their understandings of MC were not the same. Though they share commonalities, there are some differences as well. In this section of the paper, we will flesh out the commonalities as well as the distinctions to determine if anything can be gleaned for effective Christian apologetics today.

Points of Commonality

Historical Setting

Tumultuous historical circumstances thread together the lives of these two men. Lewis was fighting against the tide of naturalism, materialism, and liberalism that was sweeping through his country after two great World Wars. Baxter was fighting the onslaught of political factions, which were taking clerical garb. Each man’s unique situations brought the same problem: a weakening of religious conviction that threatened the integrity of Christ’s body.1 Both Lewis and Baxter found a way to present the gospel to the world in the midst of these difficult times, and for this God can be thanked.

Bond of Christianity

Another commonality between Baxter and Lewis can be gleaned from their respective house illustrations. Lewis believed that MC was the hallway of a house where the various rooms are connected. Though Christians find their fullest expression of Christian belief in the individual rooms, nevertheless, there was a common hall. Baxter’s house illustration is quite similar. Speaking to those who are

so solicitous to know which is the true church among all the parties in the world that pretend to it … you runne up and downe from room to room to find the house; and you ask, Is the Parlour it, or is the Hall it, or is the Kitchin, or the cole-house it? Why everyone is part of it, and all the rooms make up the house.2

A few lines later Baxter gives the interpretation:

Which is the Catholic church? Why, no part is the whole. Is it the Protestants, the Calvinists, or Lutherans, the papists, the Greeks, the Ethiopians? Or which is it? Why, it is never an one of them, but all together, that are truly Christians, good Lord!3

Thus, we find that both Baxter and Lewis held that there was a significant treasure of commonality among those who are denominationally divided Christians.

Points of Dissension

Denominationalism

Though both Baxter and Lewis viewed Christianity as a common house, what they believed should be done in the house is quite different. Lewis believed that the individual rooms were the places of rest. It is there that the tables and chairs exist and where men ought to migrate as quickly as they can. New converts should dedicate themselves to a particular denomination as soon as they could. Baxter, on the other hand, believed the rooms in the house should be boarded up.4 The tables, food, and chairs should be moved into the hallway, so that there would be no visible disunity amongst God’s people. Both men agreed that when the house was originally built there was only the common hall, and both agreed that it was through sin and human fault the rooms were individually built. However, their solutions to the problem were opposite one another.

John Frame, in Evangelical Reunion, suggests something close to Baxter’s ideal. Frame outlines a strategy for eliminating denominationalism and establishing a post-denominational phase in church history.5 Baxter’s and Frame’s ideas have always had poor reception in the church. The idea sounds attractive and is grounded in Scriptural commendation towards unity. However, the issues that divide denominations are not easily solved—especially since most of the issues are argued from the text of Scripture. For instance, how could baptism be administered in a post-denominational (PD) church? How would the church be led individually and universally? What place would tradition, Scripture, and spiritual gifts have in a PD church?6 These questions are not matters of unimportance, and many of them affect the way one views the essentials of the faith. It is for these reasons that various denominations exist in the first place, and without clear objective criteria for how the issues are to be resolved, PD Christianity will have to wait until Christ returns.

Lewis had determined denominationalism was a necessary evil. Presumably, Lewis recognized that the issues that divided Christians were significant enough to prevent complete union. If so, Lewis believed divisions were an unfortunate byproduct of current human limitation. Instead of warring over the differences, Lewis suggests that Christians accept them as differences. Christians should live in their own rooms; however they should gather often in the common hall to fight against the common enemy.

Overall, Lewis’s approach to the denominational question is superior to the approach of Baxter. First, Lewis accepts depravity and the consequence that even the saints will not be fully agreed on important matters of the faith. Second, Baxter’s conception leaves too many difficult issues unresolved. And finally, Baxter’s anti-denominational vision has never been shown to work. In Kidderminster, where Baxter ministered, he boasted, “I know not of an Anabaptist, or Socinian, or Arminian, or Quaker, or Separatist, or any such sect in the town where I live; except half a dozen Papists that never heard me.”7 Undoubtedly Baxter believed he had accomplished a PD type of community. However, others looked at his work and instead of identifying it as PD, they called it Baxterianism.8 Decisions in Kidderminster had to be made about church government, mode of baptism, and like issues. When those have been made, no matter the intention, a distinctive group of Christians has naturally arisen. Thus, PD Christianity is a noble goal, but it cannot be accomplished without a crystal-clear, objective means of determining all ecclesiastical questions.9

Notes

1 Keeble, “C. S. Lewis, Richard Baxter,” 27.

2 Baxter, The Practical Works, 4:736.

3 Ibid.

4 One might believe it is a leap to move from Baxter’s criticism of separation within the body of Christ to his view that denominations should be “boarded up.” Two aspects of what has been stated before lead the present author to this view. First, Baxter sought to establish a local church body as an ideal for how local churches should function. As indicated earlier, Kidderminster did not have denominations, and Baxter was clearly proud of the achievement. Second, Baxter’s criticism of creeds suggests that any distinguishing mark of a particular group (e.g., a denomination) was destructive to the church. Combined, these two facts suggest that Baxter’s ultimate vision was for a church without denominational divisions.

5 John M. Frame, Evangelical Reunion: Denominations and the One Body of Christ (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1991).

6 Frame seeks to answer many of these questions in his text. To critique his arguments here is beyond the scope of this paper (see ibid.).

7 Quoted from Nuttall, Richard Baxter, 64–65.

8 Keeble, “C. S. Lewis, Richard Baxter,” 30.

9 While the Scripture is certainly the objective authority on these issues, those who hold truly to the gospel of Christ disagree about its instruction. As long as man remains in this flesh, these questions will probably remain unresolved. If nearly two thousand years cannot resolve them, little hope is reserved for agreement this side of eternity.

Tim Miller Bio

Dr. Tim Miller is Assistant Professor of Systematic Theology and Apologetics at Detroit Baptist Theological Seminary. He received his M.A. from Maranatha Baptist University, his M.Div. from Calvary Baptist Theological Seminary, and his Ph.D. in historical theology from Westminster Theological Seminary.

- 8 views

It’s interesting to me that this series has received little attention relative to the “convergence” series since both deal with similar concerns.

Namely:

- Is it possible to define a minimum core belief system that can be used as a pass/fail litmus test for those who are brothers in Christ?

- What is to be done with people who claim Christ but do not in doctrine or personal belief pass the litmus test?

- What is to be done with the plethora of “divergent” doctrines and applications that still exist among believers after the initial litmus test?

The writings of Lewis and Baxter illustrate that these concerns are not unique to the present day.

Separatist fundamentalism has espoused the same response to the two sets of people identified in questions 2 and 3. It has sought to separate/isolate itself from interaction and dialogue with both. Because of its separatist stance, it has not been effective in interacting with error in either of the sets of people in questions 2 and 3. Separatist fundamentalism does view itself as militant, but it is really not, since it does not interact (Is an army that never fights truly militant?). Its expression can be aggressive, but that aggression is usually limited to its own congregations. My sensing is that within Christianity as a whole, separatist fundamentalism is losing favor as a strategy to deal with the issues of questions 2 and 3.

My belief is that Christianity needs a more truly militant fundamentalist strategy. It needs to be willing to engage and interact apologetically and with conviction in order to persuade both professing non-Christians and false Christians. There needs to be more of Titus 1:9 and less of II Cor. 6:17. Military engagement is difficult and cathartic. It forces its participants to be well prepared for combat, to be expertly trained in their weapons and defenses. It requires personal and organizational discipline. Military engagement requires detailed study of the enemy - of his strengths, weaknesses, and fighting philosophies. It requires strategies and tactics to change based on this intelligence. It also requires humility in both victory and defeat.

I propose that it is too simplistic to say that everyone who leaves separatist fundamentalist churches are doing so due to compromise of convictions and standards. Surely some are leaving so that they can be more effective militarily - not to compromise with the world, but to actually engage it and rebuke it.

John B. Lee

Discussion