What do you think about the increasing use of the word "Worldview" within Fundamentalism?

Poll Results

What do you think about the increasing use of the word “Worldview” within Fundamentalism?

It is good. Votes: 5

It is bad. Votes: 2

It is neither good nor bad. Votes: 1

Haven’t seen increased use of “Worldview” within Fundamentalism Votes: 2

Discussion

Directions in Evangelicalism (Fifth in Series)

This essay’s first appearance at SharperIron was in January of 2009. Previous installments in the series: 1, 2, 3, and 4.

This essay’s first appearance at SharperIron was in January of 2009. Previous installments in the series: 1, 2, 3, and 4.

The Gospel According to Walt

We have examined the vision of the gospel that is being propagated by Scot McKnight of North Park Seminary and by Timothy Gombis of Cedarville University. They are certainly not unique in the evangelical world. Indeed, their understanding of the gospel has become influential among an increasing number of evangelicals.

The theory, however, is not new. As an example, consider Walt. Like Scot and Tim, Walt did not wish to abandon the gospel of personal salvation. Also like Scot and Tim, he yearned for a gospel that could deal with problems that he deemed larger and more important. Here is what Walt said:

Discussion

Should NIU separate from BJU?

Using their theology of separation, when are fundamentalist leaders going to separate from BJU?

Discussion

Skirts on Men

Discussion

Proud Fundamentalist

Lots of people claim to be fundamentalists. Far more are labeled “fundamentalist” by media outlets or Christian leaders who wish to distance themselves from more traditional—or just more feisty—brethren. Those who want to use “fundamentalist” in a historic sense can only avoid confusion by using the term with qualifiers and explanations—in other words, by including context.

So when I say, “I am a proud fundamentalist,” I mean “fundamentalist” in the historic sense. Two statements from one of SharperIron’s “About” pages sum up the concept:

In a religious sense, the term “fundamentalist” was first used in 1922 in reference to a group of Baptists who were seeking to establish doctrinal limits in the Northern Baptist Convention. Their goal was to uphold the Bible and rid the convention of the philosophy of Modernism, which denied the infallibility of Scripture, rejected miracles, and gutted the Christian faith of defining principles such as the substitutionary atonement of Jesus Christ. In short, the fundamentalists thought the Northern Baptist Convention ought to at least be genuinely Christian.

…

At SharperIron we’re still clinging to the term in its historic sense. Here, a fundamentalist is someone who believes in the foundational principles of the Christian faith and also believes in separation from apostasy. Opinions vary as to the degree of separation, the process and the methods. But we are committed to the principle.

Discussion

The Danger of Defining Yourself by What You Are Against

Discussion

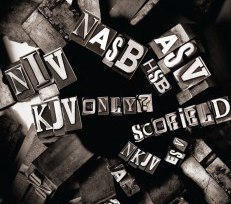

KJV Only? How a Translation Became a Litmus Test for Orthodoxy

Republished with permission from Baptist Bulletin July/Aug 2011. All rights reserved. This article is condensed from a paper presented at a Baylor University conference. A full version will be published in the Detroit Baptist Seminary Journal.

Republished with permission from Baptist Bulletin July/Aug 2011. All rights reserved. This article is condensed from a paper presented at a Baylor University conference. A full version will be published in the Detroit Baptist Seminary Journal.

This year marks the 400th anniversary of one of the most important pieces of English literature ever released. Arguably, no other book has had the widespread influence and lasting significance of the King James Version (KJV or AV) of the English Bible. Its American title is derived from King James (Stuart) the First of England (James VI of Scotland). His initial idea was for a new common Bible version, but there is no evidence that he ever authorized it for use in all English churches. Given the prevailing politics, with the Puritans agitating for religious freedom, it is unlikely that he would have attempted a formal declaration. Nevertheless, the new translation became the dominant English version and held that position for most of the next three centuries.

But with its celebrity status comes some interesting history. In the late 19th century, John William Burgon and some of his associates argued for the KJV against the Revised Version—not because the KJV was a superior English translation but because the underlying Greek text was a better Greek text than the RV used (the Westcott and Hort text).

Since the 1960s, some Christians have been debating the continued usefulness of the Authorized Version and the underlying Greek text for regular use in the life of the church. The battle over Bible versions in general, and the battle for the KJV in particular, has been a significant issue within some segments of American Protestantism. At the worst, some have come to regard American Christian fundamentalism as closely associated with the “KJV 1611.” The debate has reached the point where non-fundamentalists think the movement is cultish, and some laypeople within fundamentalism itself think that God is the One Who personally “authorized” the KJV as the Bible for the English-speaking world.

The defense of the KJV takes two approaches. Some argue that the KJV 1611 is the most accurate rendering of the original manuscripts for the English-speaking world, a position still held by some GARBC pastors. Other advocates (called KJV-only in this article) are more dogmatic, with many colorful figures advocating a range of peculiar views, for example, that the KJV is the perfect Word of God, able even to correct Greek and Hebrew manuscripts themselves. Both of these views will be examined in this article.

Discussion