Standard of Living?

One of the most telling characteristics of our culture is how we collectively determine an individual’s standard of living. The concept of a “standard of living” is something like a high-jump bar by which we gauge the quality of our daily lives. Some people cannot clear the bar and we say they experience a “low standard of living.” Others clear the bar with considerable room to spare and we declare that they enjoy a comparatively “high standard of living.” Those who fall between these two sub-sets keep jumping, but never seem quite sure if they clear the bar or not.

Irrespective of how high we are able to jump, one thing is certain: our culture naturally defines standard of living in terms of economic prosperity. The bar by which we gauge standard of living is hoisted to its current height by prevailing economic conditions and expectations and then we orient ourselves toward attaining that height—and then some.

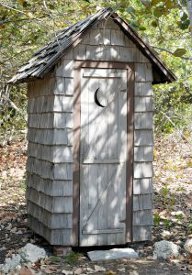

It is interesting to observe that the bar which distinguishes between high and the low standards of living has been steadily elevated throughout the latter half of this century. As case in point, I recently enjoyed an evening meal with my extended family. It was one of those summer time delights—grilled chicken breast, calico bean dish, corn on the cob, fresh baked rolls, potato salad and iced tea. Wow! The conversation among the elders at the table turned (as only an intimate family can turn it) to middle-of-the-winter trips to the outhouse. This topic veered off ever so naturally into a discussion of the history of toilet paper, when, on cue, my mother divulged her recurring account of the days her family could not afford said fibrous luxury. As the account always goes, she reminded us of the qualities of various alternative sources of “paper” that were used for this daily duty. (It seems that the wrapping on summer peaches was the paper of choice. My mother still speaks as if peach season were Nirvana.) I went home that night very thankful that the standard of living in America has improved so dramatically.

It is certainly not just toilet paper that has improved our living standard over the course of the twentieth century. Add to the list almost anything: from houses and cars to communication systems and the myriad of technological advances over previous generations.

Yes, in almost every way our standard of living has dramatically improved; if, that is, we blindly accept the prevailing criterion by which that standard is determined. I would like to propose that we should not so readily accept this criterion.

Discussion

Thinking Biblically about Poverty, Part 1: What is Poverty?

Why are the poor poor?

It seems few are asking this question anymore—just when we need most to be asking it, just when interest in helping the poor has apparently reached an all time high.

I don’t recall ever hearing and seeing so many radio and TV ads for charitable causes, donation displays at retailers’ cash registers, or businesses prominently displaying how they’re helping the needy (or how they’re saving the world from environmental catastrophe—or both).

Evangelicals seem to be giving poverty more attention as well—in increasingly passionate terms and from quarters not historically known for that emphasis. Witness this observation from Southern Baptist, David Platt:

Meanwhile, the poor man is outside our gate. And he is hungry…. We certainly wouldn’t ignore our kids while we sang songs and entertained ourselves, but we are content with ignoring other parents’ kids. Many of them are our spiritual brothers and sisters in developing nations. They are suffering from malnutrition, deformed bodies and brains, and preventable diseases. At most, we are throwing our scraps to them while we indulge in our pleasures here….

This is not what the people of God do. Regardless of what we say or sing or study on Sunday morning, rich people who neglect the poor are not the people of God. (Radical: Taking Back Your Faith from the American Dream, p.115)

Discussion