Why Do (Some) Seminaries Still Require the Biblical Languages?

The following is reprinted with permission from Paraklesis, a publication of Baptist Bible Seminary. The article first appeared in the Summer ‘09 issue.

The following is reprinted with permission from Paraklesis, a publication of Baptist Bible Seminary. The article first appeared in the Summer ‘09 issue.

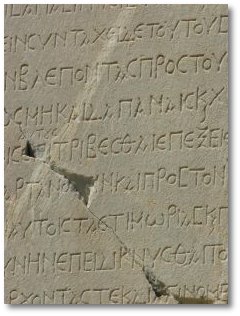

Why learn Hebrew and Greek?

I want to address just one facet of the question in this essay. The primary purpose of Baptist Bible Seminary is to train pastors. We have made a deliberate choice to focus on only one narrow slice of graduate-level biblical-theological education. I am thinking first and foremost of the pastor when I think of the place of the biblical languages in the curriculum. In its biblical portrait, the central focus in pastoral ministry is the public proclamation of the Word of God. There are certainly other aspects of pastoral ministry, but it can be no less than preaching if it is to be a biblical pastoral ministry.

How does preaching relate to the biblical languages?

I have some serious concerns about the state of the pulpit these days. My concern could be stated fairly well by adapting the wording of 1 Sam. 3:1 and suggesting that biblical preaching is rare in our day, and a word from God is infrequently heard from our pulpits. Some of today’s best known preachers echo the same sentiment. John Stott, for example, says that “true Christian preaching…is extremely rare in today’s Church.”1

As those who stand in the pulpit and open the Word of God to a local congregation, pastors have the same charge as that with which Paul charged Timothy: “Preach the Word” (2 Tim 4:2). That is an awesome responsibility. The apostle Peter reminds us that “if anyone speaks, he should do it as one speaking the very words of God” (1 Pet 4:11).

The Word of God is a most precious treasure—equal to our very salvation in worth, for if we had no Bible we would know nothing of God’s Son, the forgiveness that His cross-work provided, and the new covenant relationship which that work inaugurated.

Although the Word of God has been given for all, the pastor is entrusted with the Word of God in a special sense due to his primary responsibility of proclaiming that Word to a congregation. Handling the Word of God correctly is an enormous responsibility. As James exhorted his hearers, “Not many of you should presume to be teachers, my brothers, because you know that we who teach will be judged more strictly” (James 3:1).

There ought to be a very real sense in which the pastor recognizes and acknowledges his inadequacy for such a great task. Richard Baxter, the famous 17th century preacher, reminds us that “it is no small matter to stand up in the face of a congregation and deliver a message of salvation or condemnation, as from the living God, in the name of our Redeemer.”2

Preaching is directly influenced by our theology. If we really believe, not just as a matter of academic statement, but as genuine convictions, that the Bible is God’s revealed truth, inspired and inerrant in the originals, then our preaching and teaching of that revelatory corpus must, of necessity, be based on our careful study of the text in the original languages.

There is no other way to have the immediate confidence necessary to undergird our proclamation of “thus says the Lord.” If you cannot read the Old Testament in Hebrew and the New Testament in Greek, you will always be at the mercy of those who claim to to be able to do so. The pastor may never become a scholar in the languages, but he absolutely must learn to understand the text as God saw fit to have it written. He must learn to read the text, use a lexicon, and evaluate and profit from the commentaries and grammars. He cannot depend on software to do this for him.

Yes, any of the decent language-based software tools will parse every word for you, but if you don’t know what to do with that information, what good is it? There is a world of difference between pieces, even mountains, of data and comprehension.

Works Cited

1 Between Two Worlds: The Art of Preaching in the Twentieth Century (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1982), 15.

2 The Reformed Pastor, edited and abridged by Jay Green (Grand Rapids: Sovereign Grace, 1971), 17.

Dr. Rodney Decker has served as Professor of Greek and New Testament at Baptist Bible Seminary since 1996. He has published several books and scholarly articles. He also edits and maintains NTResources.com and has created several specialized TrueType fonts for Greek.

- 541 views

[Jay C.]Swiss. Switzerland is divided into two main sections, one French-speaking, the other German-speaking. (Actually, most Swiss probably speak both to some extent.) German-speaking Swiss theologians, I think, are often confused with Germans.

BTW, are Balthusar and Barth German or Swiss? For some reason, I had it in my head that they were German, but Wikipedia (not always the most reliable source of info) said that they were Swiss, not German.

My Blog: http://dearreaderblog.com

Cor meum tibi offero Domine prompte et sincere. ~ John Calvin

(I cheated and used a webpage to translate for me ;) ).

"Our task today is to tell people — who no longer know what sin is...no longer see themselves as sinners, and no longer have room for these categories — that Christ died for sins of which they do not think they’re guilty." - David Wells

[Charlie]I’ll bet this confusion would mostly only happen to Americans, since we are so language insensitive! I speak German, and I can tell you that Swiss German sounds so different, it’s very hard to understand for those who are only used to Hochdeutsch (the main German dialect), and at least in conversation, some of the expressions are different. However, I’ve never read any works by German-speaking Swiss, and they may read very similarly to regular German, or so much the same you couldn’t really tell unless you are a native.

Swiss. Switzerland is divided into two main sections, one French-speaking, the other German-speaking. (Actually, most Swiss probably speak both to some extent.) German-speaking Swiss theologians, I think, are often confused with Germans.

Many Swiss really amaze me though. In addition to the French and German sections, they also have a (smaller) Italian one. The first time I visted Europe, I started in Switzerland, and on the train, the conductors had no trouble speaking all 3 of those languages, plus English! I didn’t speak any German at the time, but if their command of the other languages was as good as their command of English, then they are completely fluent in all of them. My education certainly felt inadequate!

Dave Barnhart

[Charlie] German-speaking Swiss theologians, I think, are often confused with Germans.Only until the Germans listen to them speak! :bigsmile:

Jay C. I would highly recommend True discipleship (GEr. “Nachfolge”) by Bonhoeffer. You get the idea, when reading it, that he is somewhat like a zealous youth pastor who has only been saved a few years (which was actually the case. He came to living faith about four years before he wrote it). His book, “Life Together” is also good. His theological works have some awful things in them - but he wrote them before he came to know Christ, and before he had ever done much Bible reading. Remember when you are reading True Discipleship too, that his concept of the church is the Lutheran Volkskirche, filled mostly by baptized people who had never received Christ in their hearts, and thus had no concept of discipleship, or why it is even necessary. I would enjoy hearing what you think, after you have read it.

Jeff Brown

IOW, as an English language only preacher I can get enough to feed my flock and keep them healthy. If I had a few more language tools in my tool box, I could feed them a richer and more varied diet. Sorry, brethren, I’m spoiled by having David Innes as my senior pastor at Hamilton Square Baptist Church.

[Rodney Decker][Rob Fall]That’s a great analogy for illustrating the value of the languages rather than depending on good, but secondhand tools. Thanks. (I’m going to quote that on [URL=http://ntresources.com/blog/?p=892] my blog[/URL].)

As a Californian, I understand that you can only get so much gold from panning. You need different tools to mine out a vein of gold.

Hoping to shed more light than heat..

With this discussion of German higher criticism, I have found the testimony of Eta Linnemann to be very interesting. Her book “IS THERE A SYNOPTIC PROBLEM ?,” Baker, 1992 may be of value to any wondering about the esteemed scholarship that has come from some in the European Universities. She was a renowned NT higher critical scholar who was converted and rejected her prior academic viewpoint.

In my prior post I stated:

Many European Universities have no or minimal Greek and Hebrew requirements in their Doctoral programs. It depends on your research area. It is all about research and your contribution to general theological or biblical subjects through your research as seen in the dissertation.

Please note I said many not all and that it depends on your research area.

My understanding is somewhat confirmed by others with a more first hand knowledge. This is important for our understanding of the state of some American theological schools. Some have faculty that have a B.A, in a secular subject, a two year MA in biblical or theological subjects (or a 3 year M.Div.), and then a European PHD. This can often represent one having not had the full courses in good conservative theology and biblical subjects (including languages) expected of a conservative graduate level professor. He may be teaching without having been adequately taught. Also, it is important to see where the Masters was earned, and if they would have been mentored in sound conservative theology and biblical subjects before flying off to Europe where they may study that which is adversarial to their faith.

In my opinion, the PHD or THD from a good Fundamentalist or conservative evangelical seminary today represents a much better education than the European education. One needs to learn from others on how to read a theological map before entering into the Forrest of a European research degree. The European Universities have experienced many changes beginning with WWI and then after WWII. This may especially be true of the German Universities. Jeff Brown could speak to this more knowledgeably than I. But that is my understanding from studying history and historical theology. I do believe Jeff Brown returned to the Arctic circle and Central Baptist Seminary to earn his PHD. Perhaps he can confirm that. If that is so, congratulations for the completion of a long academic journey.

Some go to Europe for the prestige of a European degree. However, that prestige that remains may not be representative of present day academic reality.

For those advocating Latin: DULCE QUOD UTILE

Your point about European universities is exactly backwards, at least in part. Mark Noll, in “In Between Faith and Criticism,” notes that going to do a resarch PhD ( say at Cambridge of Oxford - still very common amongst conversative evangelicals/Reformed) was a way many conservatives avoided having to confront coursework in higher criticism. In other words, the “advantage” of the British PhD for many American Christians is that you can avoid having to do work that challenges your assumptions. Anyone familiar with the British PhD (and I know many people in British doctoral programs) knows how narrow the focus and simple the process are compared to a US PhD: You literally just write a prospectus, send it to the person you want to work with, and if they like it you come over and spend three years writing it.

Americans are often ill-prepared for this because our undergraduate work is nowhere near as specialized as a traditional British undergraduate degree (three years of highly specialized coursework that normally assumes advanced - i.e., A levels - preparation in the field), which is why American either do a masters first (Cambridge strongly encourages this) or have a substantial graduate coursework in the field (e.g. which you could get in a M.Div/Th.M depending on the program.)

So, what is far more challenging for a conservative in biblical studies is going to a prestigious American doctoral program.

What I’m saying is confirmed by critics, too. I can’t remember where, but I am sure I remember reading someone criticizing guys like Pete Enns, Kenton Sparks, et al. as being the “fruit” of prestigious but liberal Ivy programs, etc.

That’s another topic, of course, but I just use it as an example.

I don’t think there can be any serious question, however, that if what one is considering is simple academic quality and not theological orthodoxy, many prestigious schools are prestigious for a good reason: the students are better, the program more demanding, etc. What Christians’ strategy should be with respect to doctoral education is also another discussion, one that interests me but which I’ll leave alone for now.

[Joseph] Bob,

Your point about European universities is exactly backwards, at least in part. Mark Noll, in “In Between Faith and Criticism,” notes that going to do a resarch PhD ( say at Cambridge of Oxford - still very common amongst conversative evangelicals/Reformed) was a way many conservatives avoided having to confront coursework in higher criticism. In other words, the “advantage” of the British PhD for many American Christians is that you can avoid having to do work that challenges your assumptions.

SNIP.

Hoping to shed more light than heat..

I have tried twice to link to Eta Linneman’s testimony and failed. Just Google her name and it will be the first item.

As she affirms, higher criticism is more philosophy than historical research. Most involved in this methodology have the assumption that the Bible is the result of man’s philosophy and reject the supernatural. Much has been written by conservatives refuting these arguments. Today, reading higher critical theories is like reading last centuries newspapers. It is old, rehashed, and empty headed reasoning. Most conservatives may not want to waste the time studying under such dead faith purveyors of bad reasoning. We can read their theories and refute them without wasting valuable time studying with them.

Joseph, you appear to give too much value to pursuing that which is of little value. Once you get through with your BA at Liberty U. you should pursue a degree at a Fundamental or Conservative Seminary. After that you may be in a position to better evaluate graduate theological education. Forget the prestige of academia as defined by a liberal unbelieving academic world. It is like seeking to satisfy your sweet tooth with cotton candy.

Edit: fixed link above

I nor my teacher would say that those who do not know the original languages cannot see Scripture for all it is worth. However, once you have learned the languages you are able to see what others cannot. Things that are embedded within the structure of the given language due to its linguistical characteristics.

Another benefit to the original languages is that will help you wade through the commentaries and hopefully cut down your technical prep-time as you can do more of it yourself and be able to spend less time in the commentaries.

Just some thoughts that are not meant to be exhaustive.

2 Tim. 2:15

“advantage”… you can avoid having to do work that challenges your assumptions.Just want to point out, FWIW, that assumptions will go unchallenged either way. It’s just a question of which ones. The assumption that more rigorous is better, for example is not challenged at the Ivy League schools—nor should it be, but I’m just illustrating. I think they also do not challenge the assumption that assumptions should be challenged.

My point is just that the pursuit of knowledge—whether via academics or some other route—is always carried on with some convictions already in place and treated as givens. I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say that what Christianity is all about is taking the central doctrines of the faith—i.e., taking what God has told us—as givens.

(That said, I’m glad many true believers pursue a thorough knowledge of many of the bigger errors that have shaped our times. They enable us all to better recognize and combat these ideas. But this is not quite the same thing as having your

Views expressed are always my own and not my employer's, my church's, my family's, my neighbors', or my pets'. The house plants have authorized me to speak for them, however, and they always agree with me.

I have read two of Eta Linnemann’s books. She was invited by Campus Crusade to the U of Erlangen for a series of lectures about 10 years ago. I got to attend them all. She was quite controversial. Her points were all correct. The only negative point was that she got rather involved in one of her lectures and lost just about everybody, I think. Her conversion, both spiritual and theological, was rather thorough. When she realized her error in following Higher Criticism, she threw out all the works that she had written advocating it. I think that was because she came to such a stark realization that she had a real sin problem, and that Liberal Theology was completely powerless to help her. People with a simple Bible belief had the answers for her that helped her out of her crisis. The fact that she had grown up in a Pietist family, I think, also gave her truth to begin with, so that she could make the turn.

Most historical studies of Liberal and Contemporary Theology will confirm what Linnemann argues. Higher Criticism was created by subordinating theology and textual research to current philosophy (e.g. the Tendenzcriticism of the Tübingen school was based on Hegelian Philosophy; Bultmann used Existential Philosophy as the grid for NT interpretation). The Enlightenment changed everything in Theology, but only because theologians decided to subordinate theology and Bible research to the principles of the philosophs of the Enlightenment. Prior to 1600, theology determined what direction philosophy would go. It is one thing to interact with secular reasoning. This must be done if the Gospel is to make progress. But subordinating your faith and theology to the dictates of secular philosophy is quite a different matter.

Jeff Brown

If I had addressed it at all, I would have said: there is no hard and fast rule. Some people would simply have their faith destroyed, given their background, knowledge, analytic capacities, etc. from going to such a school. Others would be able to work through their studies to a deeper faith that is necessary for being a witness to those who see all of the issues and problems that those studies draw attention to and, often, create. But not everybody can or should be the person to address those problems, and only a fool would suggest otherwise - I have never done so. One has to know one’s limits, gifting, etc.

But the grenade lobbing from outside of a discipline, in this case historical-critical studies, is not convincing to anyone in the discipline (incidentally, I am familiar with Linneman). That’s fine - one may simply want to show some non-scholar why they should not be perturbed by something a Jesus Seminar person is spouting on the History Channell. But the scholar will have a huge set of detailed reasons for his position, and if you want to engage him on his turf you’ll have to be a scholar too, which is why I’m grateful for guys like N.T. Wright, Simon Gathercole, Richard Bauckham and a host of others (mostly Brits) who do recognized and respected scholarship that is, to greater and lesser degrees, critical of certain widely held positions (e.g. Gathercole published a book making a strong argument, by methods any scholar would accept, that the synoptics have pre-existent Christologies)

Moreover, the philosophical and theological underpinnings of a discipline change as the discipline changes, and knowing about nineteenth-century German theological developments, which is very useful (and, indeed, essential for any profound knowledge of most twentieth century problems), does not make one competent to address all of the discipline-specific problems a practioner in the discipline is concerned about. Most biblical scholars are not “big idea” people anyway; biblical studies attracts detail people because you have to being able to do detail work (e.g. an INTJ, like me, would not want to write a monograph on some aspect of Greek verbal aspect, unless somehow it related to a broader issue that he was concerned with). I can’t address some of the biblical scholars I know on their own terms; I have to appeal to meta-level justifications of my own positions that are ,very sensibly, not terribly convincing to them - to be persuasive to someone who’s immersed in the data of their discipline, as I said, I would also need to be a scholar in their discipline.

Finally, issues like the relation of Form criticism to Bultmannian assumptions about x, y, and z are obviously quite important (Bauckham provides a devasting critique of Form criticism in Jesus and the Eyewitnesses, one that would valuable for those that would be put off by Linneman’s more extreme and polemic critique, as many non-evangelical scholars would), but that does not get to the heart of the historical-critical method. The issue there is fundamentally whether the Bible, whatever else one may regard as (in our case the inerrant Word of God in the original manuscripts), should be read as a historical document and thus placed into its historical context, etc.

I think good biblical scholars are in a very tough position, and I’m glad to be a philosophical/theological student relative to them; but the issues they are dealing with are important and can’t be shirked by intellectually inclined Christians but nor can they be taken up, or even understood, by all Christians (intellectually inclined or not).

Discussion