In Which I Propose to Change Millennia of Church Tradition in 1500 Words

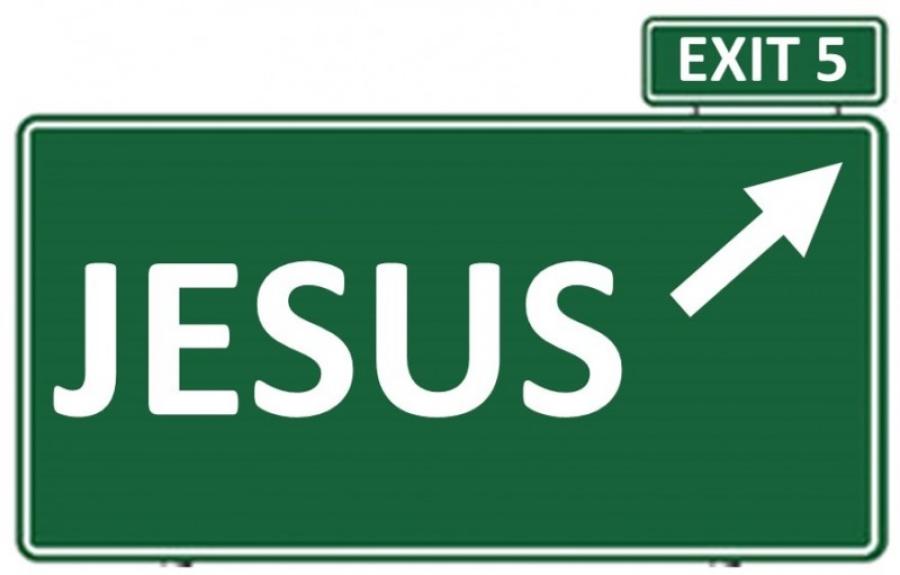

Image

Just yesterday, I preached about the New Covenant. Some church traditions celebrate Covenant Thursday on the day before Good Friday, which would be 09 April this year. I chose to hold our celebration before Palm Sunday, to kick off the Easter season. This way, before the Palm Sunday, Good Friday, and Easter services … we remind ourselves what’s so special about the New Covenant.

If you come from a dispensational tradition, the New Covenant may not be important in your church tradition. It wasn’t a focus in my own seminary training. Instead, Dr. Larry Oats organized his systematic theology lectures around the dispensations. This is fine; Maranatha Seminary is a dispensationalist school. I personally think the biblical covenants are a surer foundation to form a framework for understanding God’s plan.

I decided to tackle the subject in two parts; (1) the roadmap that leads us to the New Covenant, then (2) what’s “new” about this new covenant. This sermon was one of the harder one’s I’ve ever prepared. It’s a sermon based on systematic theology, not a passage. Even worse, it’s a really big area of systematic theology. Perhaps worse still, I’m a very mild dispensationalist who believes in Old Covenant regeneration1 and that the church is a full participant in the New Covenant, so many dispensationalist resources are of little use to me in this area.

This brings me to the point of this little article. I believe the names of the biblical covenants are very bad. Useless. They communicate nothing. We should drop them. We should change them. These covenant names are largely theological conventions; not inspired. We don’t have to stick with them. Instead of labeling the covenants by the immediate recipient, we should label them according to their purpose.

Let me explain. I’ll briefly discuss the Noahic, Abrahamic, Mosaic, Davidic and New covenants in turn.

The covenant of preservation (Noahic)

God didn’t make a covenant with Noah. He said, “I establish my covenant with you and your offspring after you,” (Gen 9:9). In fact, the covenant was with all living creatures on the earth (Gen 9:9-10). So, if we want to label covenants by immediate recipient, we should call it the “covenant with the world.”

But, even this isn’t good enough.

In this covenant, God promised to preserve the world and His creatures intact. He promised to withhold judgment, even though after the flood He acknowledged “the intention of man’s heart is evil from his youth,” (Gen 8:21-22; 9:9-11). This covenant is the basis for common grace and the reason why a people even existed for Jesus to save.2

God started over knowing it would end badly (cf. Gen 9-10), and promised to withhold similar judgment indefinitely so His grace and judgment would be known for all time. He did it so Jesus could come one day and save His people from their sins (Mt 1:21).

I suggest we can communicate better with our congregations if we call this the “covenant of preservation.”

The covenant with His people (Abrahamic)

After promising to preserve the world, God then promised to save it through a very special people – the Jewish people. Along with the first, this covenant is the fountainhead for all of God’s promises.

It’s true that God did establish a covenant with Abraham. But, it isn’t really about Abraham. The covenant marks out the Jewish people as His special people. They’re the vehicle that brings forth the Messiah, who will bless all the nations of the earth with His gospel (Gen 12:3). The Jewish people are the ones who will evangelize the world during the Millennium (Zech 8:20-23). This covenant is the basis for Mary’s hope (Lk 1:55), for Zechariah’s hope (Lk 1:72-75), and for God’s grace even as He foretold the failure of the next covenant (Lev 26:42).

This covenant is with Abraham, but it’s not about Abraham. It’s about choosing a special people to be the conduit for divine blessings upon the whole world. This is why we have a Jewish Messiah.

It should be called “the covenant with His people.”

The covenant of holy living (Mosaic)

After choosing His people, God tells them how to live holy lives while they wait for the promises to Abraham to come true. Like an airplane orbiting, waiting for permission to land, God’s people were in a holding pattern waiting for Jesus to come. So, God tells them how to live holy lives while they’re waiting.

This is a conditional covenant; “if you will indeed obey my voice and keep my covenant,” (Ex 19:5). Like an arrangement with a troubled teenage son, it established rules and boundaries. Breaking the laws, in and of themselves, did not get you kicked out of the family but disciplined within it.

This covenant taught people about themselves – they were sinful. It taught people about God – that He is holy and righteous and punishes sin. The ceremonial laws were object lessons to teach us about Christ. The civil laws were general principles of righteousness applied to a specific context. The moral law was a mirror to show us our true nature, a general restraint on sin, and a vehicle for nudging His people towards greater holiness.

This covenant taught God’s people how to live and love Him while they waited for the promises of the previous covenant to come true. Their failure is ours, because we’d do no better. It tells us we’re not good people. It tells us that, even given divine promises with evidence, we still won’t obey. It tells us we need a permanent solution to our criminal nature. We need a divine intervention in our lives to make this happen.

Jesus is the one who came to do this.

Labeling it “the Mosaic covenant” tells Christians nothing. It ought to be called “the covenant of holy living.”

The covenant of the king (Davidic)

While they waited for God’s covenant promises to be fulfilled, God gave His people a king to rule over them. He established a dynastic line through a boy named David. He said a man from this line would rule over His people and be His royal representative on earth.

God promised David He’d subdue all his enemies (1 Chr 17:9-10), but this never happened. But, Jesus (the “Son of David;” Mt 1:1) will do it (Ps 2, 110). He said He’d establish this dynasty through David (1 Chr 17:10), and this dynasty would last forever (1 Chr 17:11-12). But, the throne sits vacant. Jesus will fill it.

God said this king would be like a son to Him, and He’d be like a father to the king. There would be a familial closeness. Again, David’s throne is vacant and David committed many sins. His descendants were worse. Jesus is the “son of David” (Mt 1:1) who will fulfill this prophesy. Jesus isn’t God’s literal son; the “Father” and “Son” language expresses a closeness of relationship, not physical derivation.

This covenant isn’t about David. It’s about the promise of a good, perfect, eternal king descended from David who will be God’s perfect representative on earth for all eternity. That person is Jesus.

To call this the “Davidic covenant” is misleading. It’s really the “covenant of the king.”

Mile markers on the road to Jesus

In my sermon, I expressed these covenants as four, individual mile markers leading the Bible reader to Jesus of Nazareth. The fifth mile marker is Jesus.

- preservation: it didn’t solve the sin problem, but instead God preserved the world so He could solve it through His Son

- His people: God chose the Jewish people to be the vehicle for this new and permanent solution. Jesus is the descendant from Abraham who will bless people from all over the world, make it happen, and form a new family.

- holy living: God told His people how to hold the fort, love Him, live holy lives, and maintain relationship with Him through the priests and the sacrificial system until the new solution arrives. They failed; that’s why Jesus came to fulfill the terms of that covenant by being perfect for His people.

- king: God chose a dynasty to represent Him, love Him, and lead people to do the same. Jesus is that king.

This all leads to Jesus, who enacts a new and better covenant based on better promises (Heb 8:6). These “better promises” are summed up with one word; peace! In the New Covenant, Jesus (1) gives His people a new and better relationship with Him, (2) has a pure covenant membership, and (3) permanently blots out their sins.3

For these reasons, while the “new covenant” term is biblical language, perhaps it’s best to call it “the covenant of perfect peace.”

I believe these name changes communicate better. They focus on the covenant’s purpose, rather than the immediate recipient. In this way, the new names mean something. They teach the reader. They tell a story.

The old names … not so much.

Notes

1 But, then again, so did Rolland McCune (A Systematic Theology of Biblical Christianity, 3 vols. [Detroit: DBTS, 2006-2009], 2: 267-280). Heh, heh …

2 Robert Letham, Systematic Theology (Wheaton: Crossway, 2019), 442-443.

3 I am generally following F.F. Bruce here, while re-phrasing the first two points: “This new relationship would involve three things in particular: (a) the implanting of God’s law in their hearts; (b) the knowledge of God as a matter of personal experience; (c) the blotting out of their sins,” (Epistle to the Hebrews, rev. ed., in NICNT [Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1990; Kindle ed.], KL 2170 – 2171).

Tyler Robbins 2016 v2

Tyler Robbins is a bi-vocational pastor at Sleater Kinney Road Baptist Church, in Olympia WA. He also works in State government. He blogs as the Eccentric Fundamentalist.

- 34 views

Tyler, I really love this way of explaining the covenants. I will begin the section of Genesis on Noah in a couple of weeks and you have now given me exactly the right way to explain this covenant. Thank you!

[TylerR] For these reasons, while the “new covenant” term is biblical language, perhaps it’s best to call it “the covenant of perfect peace.”

Or, as Hebrews refers to it: “rest” (or κατάπαυσις).

THoward: I chose “peace” because that seems to sum up the point of Jesus as high priest. I thought it was the best term to do that and communicate something to the congregation. “Rest” does the same, though!

Ben:

All the best on your series on covenants!

I was worried about flattening out the covenant promises by this arrangement. But, I guess that’s the way it goes! This was only part of the sermon, not the whole thing, so I had to move quickly. But, it reflects my very mild dispensationalism in that it focuses on God’s overarching plan rather than some alleged dispensation + test, repeated seven times. My arrangement is almost “covenant of grace-ish” in its focus on Christ.

I think the distinction between Israel and the church remains in eternity, but are functionally meaningless in eternity, the same way one guy is from Seattle and another may be from Berlin. So, depending on how you want to interpret it, I fail to meet even the first of Ryrie’s sine qua non.

This means dispensationalists may be uncomfy with my naming suggestions. But, I made them up because I wanted to communicate better to the congregation. I think they do that!

Tyler is a pastor in Olympia, WA and works in State government.

I like the way the names of the covenants as you’ve titled them communicate meaning as opposed to simply being titled after the recipient. Nice work!

I think Ephesians 2 might also fit nicely into your theme of a covenant of perfect peace.

A nice teaching tool. I might use it!

Views expressed are always my own and not my employer's, my church's, my family's, my neighbors', or my pets'. The house plants have authorized me to speak for them, however, and they always agree with me.

One thing the covenant guys will immediately object to is the absence of the adamic covenant. What say you, Tyler? True covenant or made up covenant?

Made up.

Tyler is a pastor in Olympia, WA and works in State government.

Here is the sermon. Note: I made a terrible mistake by moving the camera four feet from it’s normal spot and lost about 75% of the lighting. I moved it back now. Sorry for the poor lighting:

Tyler is a pastor in Olympia, WA and works in State government.

Tyler, this is a helpful approach. (But good luck on changing centuries of traditional language!)

G. N. Barkman

[G. N. Barkman]Tyler, this is a helpful approach. (But good luck on changing centuries of traditional language!)

It only takes a spark–everyone now–to get a fire going…

Discussion