Theology Thursday - Ernest Pickering on "New Evangelicalism"

Image

Donald Pfaffe, "Views Of New Evangelicalism," CENQ 02:2 (Summer 1959)

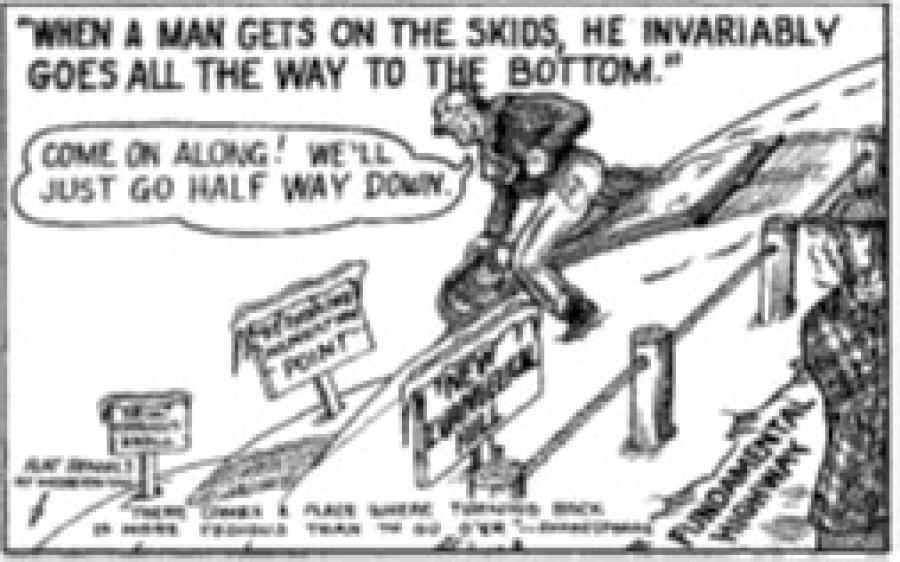

In the spring of 1959, Ernest Pickering wrote an article for the Central Bible Quarterly entitled “The Present Status of the New Evangelicalism.”1 This was only one of the first in an eventual avalanche of articles written by passionate and articulate fundamentalists, beginning in the late 1950s, as the breach between the “New Evangelicalism” and “Fundamentalism” became, for many men, a bridge too far.

Elsewhere, Robert Ketchum wrote to GARBC churches and pleaded with them to not participate in Billy Graham’s crusades. To do so, he warned, would be “the same in principle as going back into the [American Baptist] Convention for a season.”2

In the summer of 1959, William Ashbrook (also writing for the Central Bible Quarterly) solemnly warned his readers about the “New Evangelicalism.” He thundered forth, “First, it is a movement born of compromise. Second, it is a movement nurtured on pride of intellect. Third, it is a movement growing on appeasement of evil. And finally, it is a movement doomed by the judgment of God’s holy Word.”3

This isn’t the language of diplomacy! The gauntlet had been thrown down, and Pickering’s article was one of the opening salvos fundamentalists launched to warn its constituents about this insidious threat.

One of the most significant theological movements of this generation is exercising an increasingly large influence in American church life. It has arisen out of the soil of American fundamentalism. The distinguished character and ability of its leaders and the wide-spread exposition of its principles are combining to assure it a ready hearing among many conservative ministers and laymen today.

By common usage this movement has come to be known as the “new evangelicalism.” Basically, it is an attempt to find a meeting place between liberalism (with its more modern expression, new-orthodoxy) and fundamentalism. It is unwilling to espouse all the tenets of liberalism, but is anxious to escape some of the reproach attached to fundamentalism.

Probably several factors have contributed to the rise of this new approach. Apparently one of the most basic of such factors is a long-cherished desire to exert more influence and receive more recognition from the contemporary secular and religious society. A hint of this is given in this statement by one of its advocates:

And we have not always been granted even that measure of civilized respect which our competitors seem willing to accord each other in the world of scholarship and learning. Too often our best reception has been an amused indulgence…” (Christianity Today, March 4, 1957).

Some evangelicals have for years chafed at the bit because their classification as fundamentalist precluded any serious consideration of their thought and writings by the masses of our country. The bitter pill of reproach, isolation, and derision because of their theological position has been a difficult one to swallow. They have longed for acceptance as bona fide religious leaders among the recognized religious groups of the day. This driving motive has compelled them to change their approach in order to better conform to the pattern of the day, and so seek to make themselves acceptable.

Coupled with this has been an unwillingness to continue in a constant, vigorous defense of the faith. New evangelicals express impatience and disdain with those who expose the sin and error of apostasy and long to forget the whole fundamentalist-modernist controversy and move on to something more “constructive.” They have grown weary in the battle, and have decided that the advice of the old frontiersman is wise, “If you can’t lick ‘em, jine ‘em.”

The Principles of The New Evangelicalism

The new evangelicalism is a very recent movement, an emerging movement, and hence it does not as yet present itself in any highly organized form nor have its principles been all thoroughly crystallized. However, it is not too difficult to discover their major premises by a perusal of various articles which are appearing in defense of their cause.

Friendliness to liberalism and neo-orthodoxy.

This new evangelicalism approaches the liberal bear with a bit of honey instead of a gun. It expresses the feeling that liberalism is on the wane and that conservatism is growing in many of the major denominations. So, Donald Grey Barnhouse, in a letter of apology to the Presbyterian Church for his uncooperative spirit in the past, states that, “there has been a change of circumstances and of theological emphasis within our denomination,” (Monday Morning, Dec. 20, 1954). He declares in another place that “the movement in the theological world today is definitely toward the conservative position,” (Eternity, Sept., 1957).

Feeling that theological liberals are increasingly “repentant” and are seeking Bible truth, the new evangelicals are advocating a rapprochement with them, and one editor has noted “a growing willingness of evangelical theologians to converse with liberal theologians.” This feeling has expressed itself in many ways — cooperative evangelism, acceptance of speaking engagements in liberal institutions, and in other ways. Specifically, this tenet of evangelicalism is gradually bringing its proponents into a closer relationship with the leaders of the ecumenical movement— the National and World Council of Churches.

Alva McClain, President of Grace Theological Seminary, has very aptly and forcibly put his finger upon the fallacy of this reasoning.

Does anyone really think that we might “profitably engage in an exchange of ideas” with blasphemers who suggest that our only Lord and Master was begotten in the womb of a fallen mother by a German mercenary and that the God of the Old Testament is a dirty bully? Basically, the problem here is ethical rather than theological. We must never for one instant forget that they are deadly enemies with whom there can be neither truce nor compromise, (King’s Business, January, 1957).

Disavowal of fundamentalism and hostility toward separation

The adoption of the title “evangelicalism” is in itself an expression of rebellion against fundamentalism. The statement has been made by one leading figure that “God has bypassed extreme fundamentalism.” A number of journals have produced articles severely castigating the fundamentalists for their “divisiveness,” “bitterness,” and a host of other evils. The temper of the new evangelicalism is definitely one of strong criticism of fundamentalism as a movement.

This is accompanied by a hostility to separatists, those who hold that severance from denominational apostasy is the only Scriptural course to follow. Harold Ockenga, first president of Fuller Seminary, stated at the inception of that seminary that it intended to train young men to go back into the established denominations and that it was not a separatist institution. Donald Grey Barnhouse, for the past few years, has severely reprimanded anyone who separated from an ecclesiastical organization on doctrinal grounds.

Theological elasticity

New evangelicals view fundamentalism as impossibly rigid in its theological expression. In an article setting forth some of their major beliefs it was suggested that the “whole subject of biblical inspiration needs reinvestigation,” (Christian Life, March, 1956) … In fact, they resist the use of the phrase, “verbal inspiration,” because they feel that it antagonizes liberal theologians.

This contemporary brand of evangelicalism is very broad in doctrinal inclusivism. It opposes the preciseness of dispensationalism and registers an impartiality which borders on indifference when faced with the great prophetic questions. It is cordial to Pentecostal and holiness theology, “advocating great latitude on the doctrine of the Holy Spirit. In short, it tries to embrace as wide a constituency as possible by removing as many theological obstacles as it can. This results of course in an undefined evangelicalism which bypasses many important doctrines.

Emphasis on social problems

One of the leaders of the new evangelicalism was requested by reporters to define its nature. He replied that the new evangelicalism “differs from fundamentalism in its willingness to handle the social problems which the fundamentalists evaded,” (Associated Press, Dec. 8, 1957). Vernon Grounds declares, “We must … make evangelicalism more relevant to the political and sociological realities of our times,” (Christian Life, March, 1956).

The problem the evangelicals face at this point is the rather clear fact that nowhere in Scripture is the church commissioned to agitate for better social conditions or to attempt to solve current social problems. While it is the duty of every believer to conduct himself as a good citizen and vote for whatever measures seem right, it is not the responsibility of the church of Christ to remedy all the social evils of its day. Paul never organized a “Society for the Abolition of Slavery.” He simply admonished slaves to be good slaves for Christ’s sake.

The New Testament does not reveal any divine plan for a church-sponsored social program. History teaches that preoccupation with this eventually leads to the ruin of the church.

A positivism without negativism

New evangelicals wish to avoid as much controversy as possible. The leading editorial spokesman for the position seeks a ministry which is “positive and constructive rather than negative and destructive,” (Christianity Today, March 4, 1957). The clear implication is that negativism is not constructive.

For this reason the new evangelicalism does not clearly and consistently expose the machinations and error of religious apostasy. It feels that to engage in such ministry would be to alienate the liberals and render their hopes of winning them void. To bolster their program of positivism evangelicals have branded fundamentalists as too “negative” and “reactionary.” Doctrinal controversy has been described as unfortunate and divisive.

However, John F. Walvoord answers this charge. “Fundamentalists have inevitably been controversialists, since historically they have fought the tide of liberal theology. Those who dislike controversy naturally turn away from fundamentalism,” (Eternity, June, 1957, p. 35).

An obedient church must contend with error as well as propagate truth.

The Impact of The New Evangelicalism

Compromising theologies are not new in the Christian church … The two extremes of liberalism and fundamentalism are bound eventually to bring forth a mediating effort such as the new evangelicalism. Very rapidly the new evangelicalism is cohering into a definite theological movement. It already can lay claim to its own leaders, its schools, and its magazines. It has become a force which cannot be ignored in Protestantism today.

For any honest observer it is obvious that the new evangelicalism is dividing the conservative camp. Many conservatives are being swayed by the large-scale scholarly and popular presentation of the new evangelicalism. Possibly the single greatest asset to their cause is the ecumenical evangelistic technique which in metropolitan centers of the world is uniting liberals and fundamentalists and thereby subtly gaining the objective of evangelicalism — a synthesis.

On the other hand, many fundamentalists of various denominational allegiances are standing fast against the inroads of this evangelicalism and not without great opposition.

The effect of this entire movement will have to be decision. Decision on the part of all those who have in the past been identified with what is known as the fundamentalist movement. The interdenominational schools of our country are facing a decision. Will they stand for fundamentalism or will they abdicate to the new evangelicalism? For most of them it is not an easy decision for their interdenominational character relates them to leaders on both sides of the issue.

The same decision will face interdenominational missionary agencies. Many of them are reluctant to take sides in any doctrinal or ecclesiastical controversy for fear of alienating some of their supporters. However, the very nature of the new evangelicalism will demand a decision.

The new evangelicalism, while propagated by sincere and able men, is not worthy of the support of Christians. It lacks moral courage in the face of the great conflict with apostasy. It lacks doctrinal clarity in important areas of theology. It makes unwarranted concessions to the enemies of the cross of Christ. Christians everywhere should resist it steadfastly in the faith.

Notes

1 Ernest Pickering, “The Present Status of the New Evangelicalism,” Central Bible Quarterly, CENQ 02:1 (Spring 1959).

2 Robert T. Ketchum, “Special Information Bulletin #5,” GARBC, (n.d.), 4.

3 William Ashbrook, “The New Evangelism - The New Neutralism,” in Central Bible Quarterly, CENQ 02:2 (Summer 1959), 31.

Tyler Robbins 2016 v2

Tyler Robbins is a bi-vocational pastor at Sleater Kinney Road Baptist Church, in Olympia WA. He also works in State government. He blogs as the Eccentric Fundamentalist.

- 203 views

[KD Merrill]I posted this on another thread, but it certainly deserves to be mentioned again here. Pastor Carlton Helgerson was once an influential player in Neo-Evangelicalism in its fledgling days and God delivered him from it. He provides a first-hand account in his booklet titled The Challenge of a New Religion and includes a thorough definition, description and exposé of its doctrine.

Some notable quotes:

Much has been written in opposition to the questionable practices of neo-evangelicalism. Books have also appeared in defense of such practices. Yet few seem to understand what this movement really is. Something needs to be said that will explain the nature of this movement, especially for the benefit of any who might assume that our aversion is limited to its methods.

As one who was deeply involved in the movement in its beginnings and who has since watched and studied its development, I can testify with knowledge.

Neo-evangelicalism is a slanted way of thinking which, like a virus, has infected many of us to some degree. I beseech my brethren to recognize the seriousness. To what extent has this virus entered our thinking? We should let judgment begin in our own hearts lest we criticize in others what we unwittingly nurture in our own minds.

Since both proponents and opponents recognize that mixture and compromise characterize the movement, it is not unreasonable to caption it as a new religion.

An obvious departure from Biblical fundamentalism is the assumption that some parts of the Bible are less important than others. This fallacy, which too many believers already take for granted, has done much damage in not a few Bible churches.

Neo-evangelicalism professes to be most anxious to propagate the gospel. It claims that the chief purpose of God is the salvation of man. This is an error.

Because of its ingrained philosophy and slanted theology, it employs unscriptural methods. It believes that the end justifies the means. Being wrong about God’s message, it follows that neo-evangelicalism will not pay attention to God’s method.

These passages contain no indication of what theological problems are actually inherent in neo-evangelical theology. Not a bit. These quotes are, really, great examples of the kind of “scholarship” that guys like Ed Carnell were eager to get away from.

Regarding the claim that it’s “indisputable” that reputation was the driving force for neo-evangelicals, that’s false, and really betrays a chicken/egg confusion. Reality is that, whether they were right or wrong, neo-evangelicals saw their fundamental brothers as needlessly isolated (see Ron Bean’s comment on hurricane relief; the isolation continues in places), and they wanted to end that isolation and re-enter the arena of ideas. (which is, Larry, not just getting degrees, as any number of guys with a sheepskin doing manual labor can tell you)

So the goal was to re-enter the arena of ideas with the hope of bringing the Gospel into that discussion. Their distress over the mockery and rejections they got are not simply at not getting acclaim, but rather represented sadness that they had not successfully entered the arena of ideas.

Over the long haul, though, I’d argue that they succeeded, and even corrected in large part the major criticism leveled against them; weakness on inerrancy. In terms of academic quality, they’ve got really a two decade head start over fundamental institutions at least. Let’s be blunt about the matter; evangelicals of various stripes far outnumber fundamentalists, and while they won’t be seen as FBFI-style fundamentalists, their theology is largely orthodox. They’ve absorbed the lesson Christ taught “he who is not against you is for you” of Luke 9:50, the lesson that Paul refers to in Philippians 1:18.

Aspiring to be a stick in the mud.

It had been years since I read Helgerson’s book. I remember when it was new. As I read the passage I was reminded again of the tactic of creating and an unnamed, shadowy, undefined, unnamed foe by describing the foe in generalities. At the time, for me anyway, it created a distrust and suspicion of anyone outside our camp. Occasionally the “Mark and Avoid” group would call out someone by name: Graham, Palau, and later Falwell; but generally the foe remained unidentified.

"Some things are of that nature as to make one's fancy chuckle, while his heart doth ache." John Bunyan

Despite all Bro. Johnson’s well-meaning attempts (yes, I do mean that) to actually define who “convergents” are, I feel that is but the latest example of “the invisible foe” Ron is talking about. Evangelicals often want to be too inclusive, in the name of Christian love. That can be a problem, obviously. Fundamentalists often tend to be overly exclusivistic and breed a fortress, “righteous remnant” mentality (e.g. “The Village”). That, too, can be a problem

Tyler is a pastor in Olympia, WA and works in State government.

Yes, a lot of us do judge motives, but that doesn’t make it a smart thing to do. As a rule, it ends up as a “straw man” argument (I’d argue McCune’s book falls into this category) because there are usually multiple reasons that a person could have done something. It also falls into the general category of “ad hominem”; because Ed Carnell was motivated by a desire to exert more influence and receive more recognition, we can safely ignore his arguments.

I would have to guess that the clear violations of Ephesians 4:32 inherent in ad hominem and straw man attacks on neo-evangelicals most likely made them less likely to pay attention to whatever substantive criticisms fundamentalists had at the time.

Aspiring to be a stick in the mud.

[Bert Perry]These passages contain no indication of what theological problems are actually inherent in neo-evangelical theology. Not a bit. These quotes are, really, great examples of the kind of “scholarship” that guys like Ed Carnell were eager to get away from.

Regarding the claim that it’s “indisputable” that reputation was the driving force for neo-evangelicals, that’s false, and really betrays a chicken/egg confusion. Reality is that, whether they were right or wrong, neo-evangelicals saw their fundamental brothers as needlessly isolated (see Ron Bean’s comment on hurricane relief; the isolation continues in places), and they wanted to end that isolation and re-enter the arena of ideas. (which is, Larry, not just getting degrees, as any number of guys with a sheepskin doing manual labor can tell you)

So the goal was to re-enter the arena of ideas with the hope of bringing the Gospel into that discussion. Their distress over the mockery and rejections they got are not simply at not getting acclaim, but rather represented sadness that they had not successfully entered the arena of ideas.

Over the long haul, though, I’d argue that they succeeded, and even corrected in large part the major criticism leveled against them; weakness on inerrancy. In terms of academic quality, they’ve got really a two decade head start over fundamental institutions at least. Let’s be blunt about the matter; evangelicals of various stripes far outnumber fundamentalists, and while they won’t be seen as FBFI-style fundamentalists, their theology is largely orthodox. They’ve absorbed the lesson Christ taught “he who is not against you is for you” of Luke 9:50, the lesson that Paul refers to in Philippians 1:18.

With the exception of the Southern Baptists (And the return of Westminster Seminary to a more historic position), where has the Evangelical world corrected weakness on inerrancy? If anything, evangelicals are shedding or redefining inerrancy at an alarming rate.

With something like 15 million members, isn’t an official SBC position on inerrancy pretty significant? That’s a full 20% of all fundagelicals if I remember correctly. There are also denominations—e.g. EFCA and PCA—that have never wavered in this to my knowledge. So while there were neo-evangelicals who introduced weaker versions of inerrancy, and while there are churches and even denominations that pursue this, weakened inerrancy is not, as far as I can tell, that prevalent among evangelicals.

Another good sign was a few years back—Steve Davis commented on this one—about Converge (the old Baptist General Conference) eschewing open theism.

To be certain, there are places where I (or you) might differ with the applications of inerrancy some churches/denominations make—the hermeneutic might appear different—but all in all, evangelicalism does not appear to be in a headlong rush to theological liberalism.

Aspiring to be a stick in the mud.

Inerrancy is perhaps the clearest example of people talking out of both sides of their mouth, depending on who the audience is. It is also one area where “evangelicals” are weak. I think the statements from the full 1978 Chicago Statement are a very good introduction to this issue, and are very helpful. People should read them. I posted the entire statement over the period of a few weeks for Theology Thursday a few months back.

I need to read the “multiple views” book that Mohler contributed to again. Mohler was the only one who didn’t tap-dance.

Tyler is a pastor in Olympia, WA and works in State government.

Unfortunately, Bird made a far better defense of inerrancy in that book than Mohler made. But if you look at some of the recent multiple views books (Inerrancy, historicity of Genesis, Adam), the Evangelical left is winning the debate/discussion from an intellectual/writing level. Vanhoozer and Enns make a better argument than Mohler made - even though I agree with Mohler. Mohler wrote his chapter like a theological politician. Enns wrote his like a liberal OT guy, and Vanhoozer wrote his like a philosopher.

I would draw a distinction between the churches, especially the rural churches and the city churches/academic institutions. Converge/CBA/Free churches in the rural areas are much more conservative than their city counterparts. I’m not certain of any Baptist in MN who would call Bethel seminary a “conservative” institution theologically - and Bethel is really the school for Converge students (Northwestern U of St. Paul is a more conservative school).

I am less familiar with the PCA, but it is only a matter of time for the EFCA to head towards a less-conservative position - if TEDS is still considered the “E-Free” institution. Vanhoozer? Thinks that someone has an “epistemological right” to believe in the historicity of the fall of Jericho “until proven otherwise” (still claims that such a position is friendly to inerrancy). Hoffmeier? Stumbles over the Exodus in places, and falls flat in his defense of the “why” of the historicity of the early chapters of Genesis. And the number of “conservative” scholars and theologians who accept some form of evolution or scientism is increasing, not decreasing.

In other words, on a popular level - the people seem far more theologically conservative than the academicians. But as we learned a hundred years ago with the Fundamentalist-Modernist controversy, as go the institutions, so go some of the churches. On a local church level, I think that the larger issues that we will have to deal with will be inerrancy, sexuality, and origins.

[CAWatson]Unfortunately, Bird made a far better defense of inerrancy in that book than Mohler made. But if you look at some of the recent multiple views books (Inerrancy, historicity of Genesis, Adam), the Evangelical left is winning the debate/discussion from an intellectual/writing level. Vanhoozer and Enns make a better argument than Mohler made - even though I agree with Mohler. Mohler wrote his chapter like a theological politician. Enns wrote his like a liberal OT guy, and Vanhoozer wrote his like a philosopher.

I would draw a distinction between the churches, especially the rural churches and the city churches/academic institutions. Converge/CBA/Free churches in the rural areas are much more conservative than their city counterparts. I’m not certain of any Baptist in MN who would call Bethel seminary a “conservative” institution theologically - and Bethel is really the school for Converge students (Northwestern U of St. Paul is a more conservative school).

I am less familiar with the PCA, but it is only a matter of time for the EFCA to head towards a less-conservative position - if TEDS is still considered the “E-Free” institution. Vanhoozer? Thinks that someone has an “epistemological right” to believe in the historicity of the fall of Jericho “until proven otherwise” (still claims that such a position is friendly to inerrancy). Hoffmeier? Stumbles over the Exodus in places, and falls flat in his defense of the “why” of the historicity of the early chapters of Genesis. And the number of “conservative” scholars and theologians who accept some form of evolution or scientism is increasing, not decreasing.

In other words, on a popular level - the people seem far more theologically conservative than the academicians. But as we learned a hundred years ago with the Fundamentalist-Modernist controversy, as go the institutions, so go some of the churches. On a local church level, I think that the larger issues that we will have to deal with will be inerrancy, sexuality, and origins.

When it comes to Bethel and its relationship to Converge, although they are a Converge school, the converge churches (except for Minnesota) get more of their pastors and especially church planters from more conservative schools such as Grand Rapids Theological Seminary and Bethlehem Seminary.

(which is, Larry, not just getting degrees, as any number of guys with a sheepskin doing manual labor can tell you)

What does this have to do with me? Or were you talking to the other Larry? I didn’t say anything about just getting degrees. the new evangelicals wanted more than degrees. They wanted respectability and acceptance in the realm of ideas. You brought up the inability to get advanced degrees in fundamentalist circles.

it ends up as a “straw man(link is external)” argument (I’d argue McCune’s book falls into this category)

Are you saying that McCune’s book is a straw man argument? Have you read it? It is very well written with copious notes for someone who lived through much of it. You might call it a lot of things, but a straw man is one one of them. It is well documented for those who want to dig deeper.

[CAWatson]I would draw a distinction between the churches, especially the rural churches and the city churches/academic institutions. Converge/CBA/Free churches in the rural areas are much more conservative than their city counterparts. I’m not certain of any Baptist in MN who would call Bethel seminary a “conservative” institution theologically - and Bethel is really the school for Converge students (Northwestern U of St. Paul is a more conservative school).

––––––––––––

[Joel Shaffer]When it comes to Bethel and its relationship to Converge, although they are a Converge school, the converge churches (except for Minnesota) get more of their pastors and especially church planters from more conservative schools such as Grand Rapids Theological Seminary and Bethlehem Seminary.

Being a member for the past 17 years (following 28 years in IFB churches) of a large (and growing) conservative evangelical Converge church in the Minneapolis/St. Paul metro area, I’m not unfamiliar with Bethel and its relationship to Converge/the Baptist General Conference.

I believe we have ten men on staff who have (at least) an M.Div degree. Of those ten, only one is a Bethel Seminary graduate. Our senior pastor has his M.Div (2003) and Ph.D (2008) from SBTS. Some attended fundamentalist schools, including a pastor (now retired) who was a graduate of Central Seminary (from the Doc Clearwaters years).

Among the congregation, we have a large number of people who are either Bethel College/University or University of Northwestern (St. Paul) alumni (or other evangelical colleges). It may surprise some here that those folks attend services faithfully, attend ABFs, lead or attend small groups and/or Bible studies, volunteer, teach, tithe/give generously, pray, witness to their friends, co-workers, family members, and neighbors, read their Bibles, and otherwise do everything else that faithful members of fundamentalist churches may be known to do.

We also have a large number of people who have fundamentalist roots (such as me). Being within an hour’s drive of Owatonna, MN, we have a large number of Pillsbury graduates. Also graduates of Northland, Maranatha, FBBC (Ankeny) and other IFB schools. Fun fact: our most talented vocalist (imo) in our contemporary services (we have both traditional and contemporary) is a recent (within the past few years) graduate of FBBC.

And those are just the portion of the congregation who went to Christian colleges. I’d guess the majority went to secular schools.

And I’d say that easily half of the congregation has either a Roman Catholic or mainline (think “ELCA”) Lutheran background (this is Minnesota, after all). We also have many folks with thoroughly-unchurched backgrounds, and some former Mormons, Buddhists, Muslims, JW’s, and others…..

Larry, here’s where you confuse doing academic level work with getting a degree.

The idea that NEs were concerned about academic reputation is really indisputable, but I don’t think it was about the inability to get a degree in fundamental circles, as you seem to suggest. Have you read Promise Unfulfilled by Dr. McCune? He talks about the academic/intellectual issue on pp. 37-45 and then returns to it later I believe. That would be worth your to understand a bit more about this issue.

9:08 on Saturday. Yes, you did confuse getting degrees with the desire to do real academic work. And yes, I’m saying McCune’s argument is a straw man for the simple reason that it confuses the desire of doing real academic level work—competing in the arena of ideas—and reduces it to a simple clamoring for respect.

Way too much of this everywhere, and most sadly in my view in “my own tribe.” There are plenty of valid criticisms of neo-evangelicalism out there, so I really don’t even know why we would bother, even if it were indisputably true.

Aspiring to be a stick in the mud.

Here’s where the rubber meets the road - is there anybody here who would hesitate to sign the Nashville Statement, released today (I believe) by the Council on Biblical Manhood & Womanhood, out of fear it would be “cooperating” with “new evangelicals?”

For the Nashville Statement thread, see here. Please comment below if you have an opinion on the propriety of “cooperation” with new evangelicals by signing the statement.

Tyler is a pastor in Olympia, WA and works in State government.

Tyler asked:

Here’s where the rubber meets the road - is there anybody here who would hesitate to sign the Nashville Statement(link is external), released today (I believe) by the Council on Biblical Manhood & Womanhood, out of fear it would be “cooperating” with “new evangelicals.

If I apply the separation rules I learned when I was younger I would say yes because it would mean signing with Mohler who signed the Manhattan paper. I’m expecting to hear crickets.

"Some things are of that nature as to make one's fancy chuckle, while his heart doth ache." John Bunyan

Concerning the Nashville Statement: At the moment, the signatures outside of the cover page are not public. I signed it (all it wanted was my name/e-mail - not position) because:

1. I’m a pastor

2. I agree with the statement

3. I’m already on public record (I wrote for the local paper on a similar issue)

Discussion