Does Ecclesiastes Teach Epicureanism?

This article originally appeared at SI July 7, ‘06.

This article originally appeared at SI July 7, ‘06.

Does Ecclesiastes teach Epicureanism? In a word, no. Despite certain passages in Ecclesiastes that “sound” Epicurean, if we take the message of Solomon as a whole and the message of Epicurus as a whole, we discover that the two views of life under the sun are quite at odds with one another. The philosopher known for “vanity of vanities,” in the final analysis, is life-affirming, and the philosopher known for “eat, drink, and be merry” actually sucks the joy out of life.

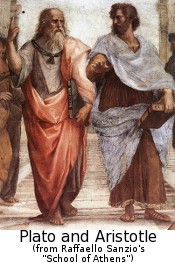

I would like first to correct what is probably a popular misconception of Epicureanism. Then I would like to lay out four contrasting points between the two views: their views of God (or the gods), of death, of humanity and human desire, and of the summum bonum–that is, the greatest good.

First, a word of clarification. Epicureanism has somehow earned a false reputation for reckless and dissipated hedonism. Actually, it is ascetic hedonism. The original Epicurus pursued maximum pleasure and minimum pain, but his strategy was anything but the “party till you drop” lifestyle that the word Epicurean brings to mind nowadays. Some parties bring pain, Epicurus observed. His strategy was actually one of detaching oneself from the cares and concerns of this world, to keep one’s mind free from turmoil (a state he called, in Greek, ataraxia). Instead of trying to fulfill all one’s fantastic desires, one should instead concentrate on keeping one’s desires simple, thus achieving a higher satisfaction rate. Why desire much and fail, since this is a lot of work and discomfort only to be disappointed?

What kind of worldview supported such a policy? This leads to the points of contrast.

Discussion