Jewish Roots Evidence for a Futurist Interpretation of the Book of Revelation

Introduction

I am a believer in the concept of biblical patterns and double or even multiple fulfillments of prophecy. The destruction of the Temple on the 9th of Av, 586 BC and again on the 9th of Av, AD 70 evidence the pattern-like nature of God’s dealings.

Still, prophecies usually have one “more literal” fulfillment (e.g., Isaiah 7:14). So it is possible to examine a verse, see how it was fulfilled somewhat near to the prophecy, but then see a fuller fulfillment in the future. Thus the Book of Revelation can have several fulfillments, one that is past, one that is ideological and not tied to particular dates, and one that is somewhat more literal, sequential, and tied to the End Times. Thus the “Futurist” approach to Revelation is not necessarily mutually exclusive, but is, I believe, primary.

Does Jewish literature leave us an example, a clue for interpreting Revelation 4-19 in particular? Although many of us tie this period to Daniel’s 70th seven (Daniel 9:25ff), others see it otherwise. So what evidence is there—outside of the Bible proper—that suggests understanding Revelation 4-19 as an expansion and detailed account of the coming seven-year world tribulation? Glad you asked.

Discussion

Book Review and Giveaway Reminder - The Gospel Story Bible

The Second Coming of Christ

I thought I was a member of a writing group on this site, or perhaps that was on another website forum. Anyways I would like feedback on my latest article just as long as feedback is only on this article and not on something else that I wrote (which would be off topic). Also I am not interested in theological debates as my audience and intended reader is dispensationalist, and I have no plan or purpose to try and persuade Reformed and others of a different persuasion.

Discussion

"Only God is Great"

The Protestant Reformation of the sixteenth century triggered a fresh wave of bloody conflict in Medieval Europe—a tract of real estate across which evolving nations had suffered tumultuous relations for many dark centuries. Protestant regions broke up Rome’s monopoly on authority in Europe. Neutralizing an authority is one thing; replacing it is quite another matter, and Europe tumbled into near-anarchy. Nation warred against nation and region against region in an all-out scramble to gain control of the rudder of Europe’s destiny.

Out of the context of these chaotic and violent times sprouted a philosophy of governance known as “Monarchial Absolutism.” Absolutist political theory held that Europe’s only hope for avoiding anarchy was for monarchs of the emerging European nations to wield unrestrained power. The cohesive influence Rome had once supplied Europe could be recovered, so it was proposed, by monarchs willing to impose their will with absolute sovereignty over their subjects. (One may detect a less than ideal environment for the human rights of dissenters under such a system. The half of that tragic subplot has never been told.)

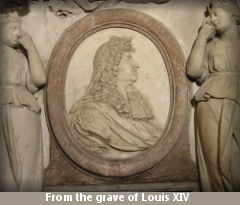

Historians generally recognize Louis XIV of France (1638-1715) as the quintessential absolutist monarch. Crowned at age five (a monarchial absolutist pre-schooler—you fill in the blanks!), Louis reigned in earnest from 1660 until his death. That translates into fifty-five years of absolute sovereignty over every aspect of French life. Every citizen, of what was at that time the most powerful nation on the continent, was expected to conform to Louis’ every belief, obey his every demand, and honor his every decision. Imagine!

Discussion

Is it possible to be saved and have little or no interest in the Word?

Poll Results

Is it possible to be saved and have little or no interest in the Word?

Yes, it is very possible and common Votes: 1

Possible but not probable Votes: 5

No, except in unusual circumstances (e.g., mentally handicapped, under heavy medication, etc.) Votes: 6

No Votes: 1

Other Votes: 1

Discussion

People of God: Eternity

Read the series so far.

Read the series so far.

As previous essays have shown, a biblical people is a nation, and a biblical nation is an ethnic unit. A people of God is a nation devoted to the worship of Jehovah. Until the constitution of Israel, no people of God existed anywhere. From the moment of its creation as a nation, however, Israel was called out from among the nations to be a chosen people, a peculiar treasure to the Lord, a kingdom of priests. Israel was the first, and for many centuries the only, people of God.

Nevertheless, even within the Old Testament, God revealed a purpose that extended to other peoples. Passages such as Psalm 67 and the miniature Psalm 117 made it clear that God wanted many nations to devote themselves to His worship. In what has to be a millennial reference, Isaiah 19:18-25 indicates that both Egypt and Assyria will someday join Israel, standing side-by-side as peoples of God. Every indication is that God always meant to have multiple peoples to call His own. And why not? If, in individual salvation, God displays the abundance of His grace by extending salvation to many (Rom. 5:15), then why, in national calling, should God’s exhibition of grace be restricted to one?

During the millennium, the pluriform grace of God will be exhibited through the calling of many peoples. Many nations will offer their worship to God through Israel’s messiah. While Israel will retain a unique position (Zech. 8:20-23), many peoples and mighty nations will come to seek Jehovah Tsabaoth and to entreat His favor.

Discussion