Dispensationalism 101: Part 1 - The Difference Between Dispensational & Covenantal Theology

Image

From Dispensational Publishing House; used with permission.

What is the difference between dispensational and covenantal theology? Furthermore, is the difference really that important? After all, there are believers on both sides of the discussion. Before entering into the conversation, there are a couple of understandings that need to be embraced.

Tension & Mystery

First and foremost, there is the need to recognize the tension—and mystery—which has characterized this and other theological discussions for centuries. There will probably never be a satisfactory answer or clarifying article that will settle the debate once and for all for both parties. There will be no end to the discussion until Jesus Christ returns (either in the rapture of His church or earthly millennial reign, in my estimation).

Man is limited in his ability to understand and articulate each nuance of theology. Not everything can be comprehended about God and His sovereign purposes. Scripture reminds repeatedly of the humbling fact that God is majestic, infinite and incomprehensible. His ways are inscrutable—He does not have to explain Himself. Passages such as Job 11:7 (NASB) ask great questions such as,

Can you discover the depths of God?

Can you discover the limits of the Almighty?

The Psalmist reminds us, “Your thoughts are very deep” (Ps. 92:5) and we “cannot attain” them (Ps. 139:6). Recall, as well, Isaiah’s record, that:

“My thoughts are not your thoughts,

Nor are your ways My ways,” declares the LORD. (Isa. 55:8)

Though there are scores of passages, one more is Paul’s doxology in Romans 11:33-34 in which he proclaims “the depth of” God’s “wisdom and knowledge,” with none to counsel Him. God transcends human comprehension, extends beyond human logic, and remains above man’s ability to reason and deduce. John Wesley was reported to have said, “Give me a worm that can understand a man, and I will give you a man who can understand God.”1 Surely “His greatness is unsearchable” (Ps. 145:3).

Bible-based, Christ-centered & God-honoring

Second, and equally important, is the need during this exchange to be Bible-based, Christ-centered and God-honoring. Though we are entitled to our own opinion, we are not entitled to our own truth. When speaking, the only basis for authority is the inspired, inerrant, authoritative and sufficient Word of God. The truth of the Bible is objective, propositional reality that is to be unpacked through cautious and diligent exegesis rather than hearsay and speculation.

Notice the third caveat here—God-honoring. When dialoging with fellow believers on opposing issues, we must be sober-minded and gracious. We cannot win the opposing side if we are being pejorative and unkind. We have no entitlement for condescending comments or judgmental jabs. We want to develop a winsome case, rather than use mockery or suggestions that the differing side is engaging in heresy on this matter. Many times in the readings of Christian academic papers there can be much unchristian cajoling that does not honor Christ. Let us honor fellow servants of Christ rather than do what one well-known evangelical did while at a rival school on this issue, when he called their view goofy. We must practice Christian charity as we honor one another in Christ.

The intent of this series of articles is not to fully flesh out the views of either dispensational or covenant theology, but to show the clear distinctions between them and why—Biblically—dispensational theology is to be preferred.

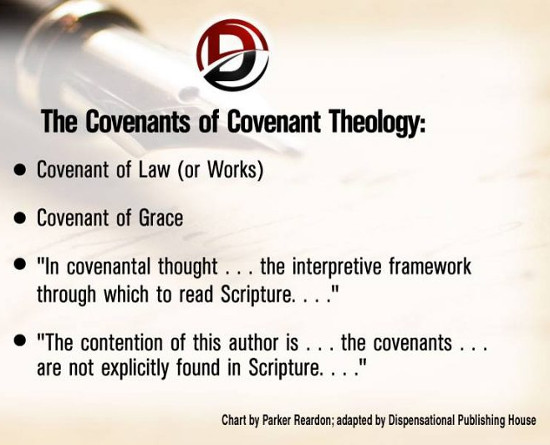

Covenantalism in a Nutshell

The terms covenantal and Reformed are often used interchangeably. There are dispensationalists who speak of being Reformed, yet the way they use the term Reformed is in respect to salvation, referring to the doctrines of grace. Another might refer to himself as a Calvinist-dispensationalist, but this is a rather awkward phrase, since Calvinism is typically used in the discipline of soteriology, not eschatology. This designation would be used to refer to men like John MacArthur and faculty from his school, The Master’s University,2 and others who have embraced the doctrines of grace and who apply a consistently literal hermeneutic, especially in the prophets, while not reading Jesus into every Old Testament verse or giving the New Testament priority.3

When trying to define a system and associate certain teachers with it, there are nuances that make such a feat difficult. For example, James Montgomery Boice was pretribulational4 and premillennial,5 yet he also practiced paedobaptism.6 Not all covenantalists are amillennial7 or postmillennial. And not all premillennialists are dispensationalists (e.g., Boice and George Eldon Ladd).

We will begin next time by thinking about the covenants in covenantal thought, using the chart below to illustrate the concepts that are involved.

Copyright © 2017 Dispensational Publishing House, Inc., used with permission.

Notes

1 Our Daily Bread, Sept.-Nov. 1997, page for Nov 6.

2 John F. MacArthur, Faith Works (Dallas: Word Publishing, 1993), p. 225.

3 More of these particulars will be augmented later in the series.

4 Pretribulationism teaches that God will remove His church from the Earth (John 14:1-3; 1 Thess. 4:13-18) before pouring out His righteous wrath on the unbelieving world during seven years of tribulation (Jer. 30:7; Dan. 9:27; 12:1; 2 Thess. 2:7-12; Rev. 16).

5 Premillenialism teaches that Jesus Christ will return to earth and rule with His saints for a thousand years. This is a time where He lifts the curse He placed on the earth and fulfills the promises given to Israel (Isa. 65:17-25; Ezek. 37:21-28; Zech. 8:1-17), including a restoration to the land they forfeited through disobedience (Deut. 28:15-68).

6 Paedobaptism is the practice of baptizing infants or children who are deemed not old enough to verbalize faith in Christ.

7 Amillennialism is the belief that the thousand years referenced by John in Revelation 20 are not a literal, specific time.

Parker Reardon Bio

Parker Reardon is a graduate of Word of Life Bible Institute, Pensacola Christian College and The Master’s Seminary, where he received a doctorate in expository preaching. He is currently serving as the main teaching elder/pastor at Applegate Community Church in Grants Pass, OR, and as adjunct professor of theology for Liberty University and adjunct professor of Bible and theology for Pacific Bible College.

- 259 views

Do we begin with our rules of hermeneutics before we open Scripture, or do we study Scripture to discover rules of hermeneutics used by Christ and the Apostles?

This seems to put you on the horns of a dilemma because we have to start with “our rules of hermeneutics” to even study the Scripture to find out “their rules of hermeneutics.” No one approaches any text or communication devoid of “rules of hermeneutics.” And most of the time, the rules come quite natural because we do it every day. (I still don’t know why people abandon it when we come to Scripture.) If we can’t trust our hermeneutics to understand the OT, how can we trust it to understand the NT to know what their “rules” were? What if we start with the presupposition that there is no conflict at all? That, to me, is the right place to start. But I don’t want to be repetitive.

More to the point, this is why Longenecker’s article and Walton’s article is important and helpful. We don’t really even know what the apostles did or what their hermeneutic was. When you see the variety of ways the the NT uses the OT, it seems that they don’t even know what they did. It does not appear to be a conscious method. Longenecker says, “There is little indication in the New Testament that the authors themselves were conscious of varieties of exegetical genre or of following particular modes of interpretation. At least they seem to make no sharp distinctions between what we would call historical-grammatical exegesis, illustration by way of analogy, midrash exegesis, pesher interpretation, allegorical treatment, and interpretation based on a ‘corporate solidarity’ understanding. All of these are employed in their writings in something of a blended and interwoven fashion.” (Longenecker, “Can We Reproduce the Exegesis of the New Testament”, p. 16). We are reading what they did, making assumptions about what they were trying to do, and then trying to make some sort of rules (or just “rely on the Spirit-leading” as someone put it). And evangelical scholars can’t even agree on what they did.

So if we don’t know what they did, how can we do it? The NT is not a manual for hermeneutics. I think Longenecker is correct that our responsibility to to reproduce their doctrine, not their hermeneutics.

It seems to me as well that you are underestimating inspiration as a source for their “interpretations” (which, again, are not always interpretations). To cite Walton again, ““The credibility of any interpretation is based on the verifiability of either one’s inspiration or one’s hermeneutics” (Walton 2002, 70). If we are not inspired, we are left with only the text that is inspired. And our burden must be to convince our hearers that the text says what we are saying, or to put it better, that we are saying what the text has already said. So the text must take center stage. I struggle to believe that God gave us all these words and sentences in the OT whose meaning cannot be determined by the analysis of the words and sentences together in their context.. Perhaps my dispensational education was different than yours, but I haven’t really come across this tension you seem to feel. Maybe I missed something along the way.

BTW, all four statements are quotations from Peter Enns. That’s why I said that you and others are very close to what Enns says about this. It’s almost identical to what Dennis Johnson says who is a more mainstream author than Enns. Again, my only point is that this is more prevalent than some are willing to admit.

A risky aside: I think there might be a case to be made that Enns ended up where he did on bibliology because he started down this road. It is not a necessary end to be sure, and I do not in any sense mean that you or anyone else will end up where Enns did. It would be interesting to think about it more. Perhaps once Enns gave up on the OT having real meaning in and of itself, there was no longer any reason to carry on the pretense that it was supernatural and accurate. I think Kaiser’s response to Enns in the Three Views book is pretty devastating. Bock’s is good as well.

It seems to me that if we want some recurring examples of how one NT author handled and interpreted the OT, we could examine the entire Book of Hebrews. That book cited more OT than anything else in the NT.

Tyler is a pastor in Olympia, WA and works in State government.

The book of Hebrews is a good place to begin understanding how NT authors handled OT Scripture.

G. N. Barkman

I completely agree Hebrews is a great example of the varied uses of the OT in the life of the church. Hebrews is probably the closest extended form of early preaching we have if Hebrews is a pastoral tract. That raises a lot of interesting questions and examples such as Melchizedek, or why the partial citation of the NC, or the use of Psa 110, and the like. I think Hebrews shows us that not all the NT uses of the OT are interpretations in the way we normally talk of it. It also shows us the role of inspiration that we don’t have.

But even if we understood the methods used in Hebrews, that wouldn’t be enough, would it? There would still be others.

An observations from Hebrews:

- The citation from Jer 31 about the New Covenant in Heb 8 is absolutely devastating for classical dispensationalism and that system’s understanding of the new covenant. To be more frank, it is a death blow. All classical DTs are left with is an appeal to Heb 8:13. This argument seems rather weak, given the entire point of Hebrews is that Christ’s new covenant is better, therefore the Jewish Christian audience shouldn’t go back to the synagogue. See Decker’s contribution to A Dispensational Understanding of the New Covenant.

Forgive me for painting with a broad brush, but I see two opposite hermeneutical approaches, both of which I believe are incorrect:

- To be so wedded to an Old Covenant hermeneutic that you refuse to recognize New Covenant revelation which complements and expands on the original promise, without negating it. An example of this would be some strands of hard-core classical dispensationalism, and that system’s perpetual confusion about what to do with the New Covenant.

- To be so wedded to a New Covenant hermeneutic that you refuse to recognize Old Covenant revelation which had to have meant something concrete and objective to the original audience - or else it would have been useless revelation. Covenant theology, broadly speaking, does this when it interprets the promises to Israel in so spiritual a fashion that the original audience would never have understood it that way.

Tyler is a pastor in Olympia, WA and works in State government.

Well said. Of course, Hebrews is written to…. Hebrew Christians????? I’ve always had trouble with that because of what to do with them warning passages and the distinctly OT prophetic flavor of the book. If you read Hebrews like a dispy might read Matthew 24 it is intriguing.

I agree that classic DT is a mess on the New covenant. What I call Biblical Covenantalism has no trouble with it. The New covenant (I think) is Christ (cf. Isa. 49:8). While I’m sounding crazy I may as well say that I’m crazy enough to believe that there is a triad of New covenant peoples - a three in one, in the New Creation. The covenants give the hermeneutic!

Dr. Paul Henebury

I am Founder of Telos Ministries, and Senior Pastor at Agape Bible Church in N. Ca.

I need to take some time to look at who the audience is a bit more. I’ve been meaning to do that for awhile. There isn’t enough time in the day. When I preach through it again, I’ll give it a good look.

Tyler is a pastor in Olympia, WA and works in State government.

The citation from Jer 31 about the New Covenant in Heb 8 is absolutely devastating for classical dispensationalism and that system’s understanding of the new covenant.

How so? I have never understood this argument and I have never had trouble with the NC is Heb 8. Perhaps you can make sense of it for me and tell me why I am supposed to have problems. Given the number of traditional dispensationalists who have no problem with the NC in Hebrews 8, it seems you have overstated your case at the very least. I find Bruce Compton’s handling of this to be clear and convincing.

What is the NC citation doing in Hebrews 8?

And why does the author cite only part of the NC rather than all of it?

Classical dispensationalism generally holds that the church has absolutely NO relationship to the NC. This is why, for example, Chafer believed there were actually two NCs, one for Israel and one for the church. That isn’t Compton’s position. I’m only referring to DTs who believe the church has no relationship to the NC.

Tyler is a pastor in Olympia, WA and works in State government.

Thanks Tyler. So you are not referring to traditional dispensationalists, but only to a certain segment of them, correct? I agree that many people (on all sides) have made a jumbled mess of the NC, mostly, IMO because they don’t actually read it and believe what it says. But therein lies the issue, correct?

How would you address the two questions above about the role of the NC in Hebrews 8 and the partial citation of it?

Correct. I’m referring to the old-school, classical dispensationalists who believe the church has no connection to the NC whatsoever.

As for the NC, I believe the church is a full and complete participant in it now, and “all Israel” will be, later. I preached through Hebrews a while back, then afterward came across Decker’s contribution to A Dispensational Understanding of the New Covenant, and found myself in complete agreement with him. If you want to know my position on the church and the NC, Decker pretty much sums it up.

More could be said, but I’m at work and this really isn’t the topic of this thread. My point in brining up Hebrews and the NC is that some flavors of DT seem (to me) to employ transparently desperate hermeneutics to support their system. My main point was the two poles in interpretation both sides should probably avoid, which I’ll repeat here:

- First hermeneutical mistake: To be so wedded to an Old Covenant-centric hermeneutic that you refuse to recognize New Covenant revelation which complements and expands on the original promise, without negating it. An example of this would be some strands of hard-core classical dispensationalism, and that system’s perpetual confusion about what to do with the New Covenant.

- Second hermeneutical mistake: To be so wedded to a New Covenant-centric hermeneutic that you refuse to recognize Old Covenant revelation which had to have meant something concrete and objective to the original audience - or else it would have been useless revelation. Covenant theology, broadly speaking, does this when it interprets the promises to Israel in so spiritual a fashion that the original audience would never have understood it that way.

My NT and Greek professor from Seminary believes the church has absolutely no relationship to the NC. We’ve spoken about this a bit, and he and I plan to correspond this Summer on this a lot more. I just can’t get there. Maybe I’ll change my mind … :)

Tyler is a pastor in Olympia, WA and works in State government.

Thanks Tyler. Here’s my brief response:

1. How can the church be a “full and complete participant now” in something that is not even full and complete at this point? That’s my question about about why the partial citation of Jer 31. I think there’s a reason why it is a partial citation and, in the flow of the book of Hebrews, the point of the partial citation is different than most make. The partial citation is because he is expressly not including the church in the whole NC. He is actually making quite a different point—that the OC has gone away.

2. the OC-centric and NC-centric hermeneutics still doesn’t make a lot of sense to me. Hermeneutics is hermeneutics. I know of no basis to have a different one for the OT than the NT. It’s the same one we use here and every where else we communicate. The only thing I can figure is that you are referring to something Kaiser addressed about which direction we read the Bible. Some (such as yourself it seems) want to read it backwards. It is better, IMO, to read it forward. But again, the hermeneutic is the same. You do the same thing with the words, the sentences, the paragraphs, the grammar, etc no matter which testament you are in. I still don’t know why you would trust your reading of the NT if you don’t trust your reading of the OT. The OT was written to a group of people who were supposed to understand it and believe or act in particular ways because of it. To me, that is significant because it indicates that the OT has intelligible meaning for which readers are responsible quite apart from the OT, and remember, Jesus condemns those who do not believe the OT on its own terms.

Thanks again.

Somehow, we’re completely missing each other. I’m a dispensationalist. I don’t read the Bible backward. You wrote:

I still don’t know why you would trust your reading of the NT if you don’t trust your reading of the OT. The OT was written to a group of people who were supposed to understand it and believe or act in particular ways because of it. To me, that is significant because it indicates that the OT has intelligible meaning for which readers are responsible quite apart from the OT, and remember, Jesus condemns those who do not believe the OT on its own terms.

I agree. I wrote the same thing on another thread.

Tyler is a pastor in Olympia, WA and works in State government.

Tyler, My apologies. There are several people involved in this conversation and I am apparently confusing who said what. I think the bulk of the two points I made remain relevant. Again, my apologies for confusing you with whoever said that.

I understand! I think there are about four different discussions going on right now about the same topic … :)

Tyler is a pastor in Olympia, WA and works in State government.

Discussion