Dispensationalism 101: Part 1 - The Difference Between Dispensational & Covenantal Theology

Image

From Dispensational Publishing House; used with permission.

What is the difference between dispensational and covenantal theology? Furthermore, is the difference really that important? After all, there are believers on both sides of the discussion. Before entering into the conversation, there are a couple of understandings that need to be embraced.

Tension & Mystery

First and foremost, there is the need to recognize the tension—and mystery—which has characterized this and other theological discussions for centuries. There will probably never be a satisfactory answer or clarifying article that will settle the debate once and for all for both parties. There will be no end to the discussion until Jesus Christ returns (either in the rapture of His church or earthly millennial reign, in my estimation).

Man is limited in his ability to understand and articulate each nuance of theology. Not everything can be comprehended about God and His sovereign purposes. Scripture reminds repeatedly of the humbling fact that God is majestic, infinite and incomprehensible. His ways are inscrutable—He does not have to explain Himself. Passages such as Job 11:7 (NASB) ask great questions such as,

Can you discover the depths of God?

Can you discover the limits of the Almighty?

The Psalmist reminds us, “Your thoughts are very deep” (Ps. 92:5) and we “cannot attain” them (Ps. 139:6). Recall, as well, Isaiah’s record, that:

“My thoughts are not your thoughts,

Nor are your ways My ways,” declares the LORD. (Isa. 55:8)

Though there are scores of passages, one more is Paul’s doxology in Romans 11:33-34 in which he proclaims “the depth of” God’s “wisdom and knowledge,” with none to counsel Him. God transcends human comprehension, extends beyond human logic, and remains above man’s ability to reason and deduce. John Wesley was reported to have said, “Give me a worm that can understand a man, and I will give you a man who can understand God.”1 Surely “His greatness is unsearchable” (Ps. 145:3).

Bible-based, Christ-centered & God-honoring

Second, and equally important, is the need during this exchange to be Bible-based, Christ-centered and God-honoring. Though we are entitled to our own opinion, we are not entitled to our own truth. When speaking, the only basis for authority is the inspired, inerrant, authoritative and sufficient Word of God. The truth of the Bible is objective, propositional reality that is to be unpacked through cautious and diligent exegesis rather than hearsay and speculation.

Notice the third caveat here—God-honoring. When dialoging with fellow believers on opposing issues, we must be sober-minded and gracious. We cannot win the opposing side if we are being pejorative and unkind. We have no entitlement for condescending comments or judgmental jabs. We want to develop a winsome case, rather than use mockery or suggestions that the differing side is engaging in heresy on this matter. Many times in the readings of Christian academic papers there can be much unchristian cajoling that does not honor Christ. Let us honor fellow servants of Christ rather than do what one well-known evangelical did while at a rival school on this issue, when he called their view goofy. We must practice Christian charity as we honor one another in Christ.

The intent of this series of articles is not to fully flesh out the views of either dispensational or covenant theology, but to show the clear distinctions between them and why—Biblically—dispensational theology is to be preferred.

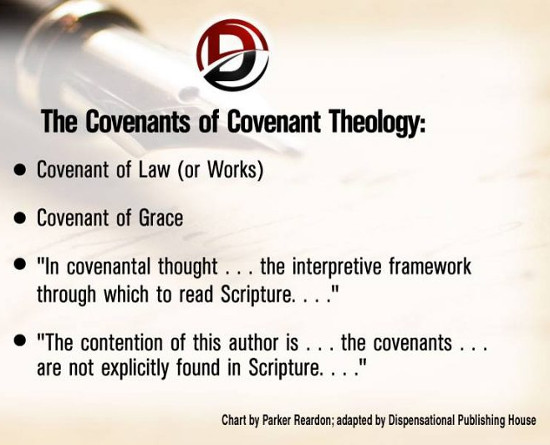

Covenantalism in a Nutshell

The terms covenantal and Reformed are often used interchangeably. There are dispensationalists who speak of being Reformed, yet the way they use the term Reformed is in respect to salvation, referring to the doctrines of grace. Another might refer to himself as a Calvinist-dispensationalist, but this is a rather awkward phrase, since Calvinism is typically used in the discipline of soteriology, not eschatology. This designation would be used to refer to men like John MacArthur and faculty from his school, The Master’s University,2 and others who have embraced the doctrines of grace and who apply a consistently literal hermeneutic, especially in the prophets, while not reading Jesus into every Old Testament verse or giving the New Testament priority.3

When trying to define a system and associate certain teachers with it, there are nuances that make such a feat difficult. For example, James Montgomery Boice was pretribulational4 and premillennial,5 yet he also practiced paedobaptism.6 Not all covenantalists are amillennial7 or postmillennial. And not all premillennialists are dispensationalists (e.g., Boice and George Eldon Ladd).

We will begin next time by thinking about the covenants in covenantal thought, using the chart below to illustrate the concepts that are involved.

Copyright © 2017 Dispensational Publishing House, Inc., used with permission.

Notes

1 Our Daily Bread, Sept.-Nov. 1997, page for Nov 6.

2 John F. MacArthur, Faith Works (Dallas: Word Publishing, 1993), p. 225.

3 More of these particulars will be augmented later in the series.

4 Pretribulationism teaches that God will remove His church from the Earth (John 14:1-3; 1 Thess. 4:13-18) before pouring out His righteous wrath on the unbelieving world during seven years of tribulation (Jer. 30:7; Dan. 9:27; 12:1; 2 Thess. 2:7-12; Rev. 16).

5 Premillenialism teaches that Jesus Christ will return to earth and rule with His saints for a thousand years. This is a time where He lifts the curse He placed on the earth and fulfills the promises given to Israel (Isa. 65:17-25; Ezek. 37:21-28; Zech. 8:1-17), including a restoration to the land they forfeited through disobedience (Deut. 28:15-68).

6 Paedobaptism is the practice of baptizing infants or children who are deemed not old enough to verbalize faith in Christ.

7 Amillennialism is the belief that the thousand years referenced by John in Revelation 20 are not a literal, specific time.

Parker Reardon Bio

Parker Reardon is a graduate of Word of Life Bible Institute, Pensacola Christian College and The Master’s Seminary, where he received a doctorate in expository preaching. He is currently serving as the main teaching elder/pastor at Applegate Community Church in Grants Pass, OR, and as adjunct professor of theology for Liberty University and adjunct professor of Bible and theology for Pacific Bible College.

- 259 views

I am happy to accept authorial intent in the place of “strictly literal” language. The problem is, this usually boils down to what the interpreter believes the author’s intent to be. But how do we know? It reminds me of the “What Would Jesus Do” campaign. It turns out to be “every man for himself” in deciding whether or not Jesus would attend a high school football game. The truth is, we do not know the author’s intent with certainty, but we can apply what seems to be the meaning as we can best understanding it, and go on from there. If that initial understanding continues to hold without contradicting other Scripture, we are strengthened in believing we have correctly understood the author’s original intent. If additional Scripture indicates a need to correct our original interpretation, we change our interpretation and proceed accordingly. We are always sifting our present understanding through additional insights from other Scriptures as we seek to improve our admittedly fallible interpretative conclusions.

This is why New Testament revelation is so significant in our interpretation of the OT. In the NT, we have the inspired interpretation of many OT passages. Some of them do not correspond to our inititial OT interpretation. What to do? Do we stubbornly cling to our initial interpretation because that seems like authorial intent to me? Or do we bow to the greater authority of inspired Scripture and correct our initial understanding. It may be difficult to reset our original conclusions, but submission to divine inspiration requires that we do so.

G. N. Barkman

[Paul Henebury]…………

As for “Land” and Romans 4:13, Paul is speaking about justification, not the land promise. I simply reproduce what I have written on SI before:

“If we look at Romans 4:13 your reasoning depends upon reading “world” (kosmos) as “planet earth” or “all the lands of the earth.” If such was Paul’s meaning then we could go with the amendments to Genesis 15 (although not without some difficulty regarding continuity). But this is not necessary because the Apostle does not have the land promise in mind in Romans 4. The context is justification to salvation, not Israel’s land grant. Even John Murray (Romans 141-142) recognizes this. A more recent commentator writes that,

“…in speaking about God’s promise, he [Paul] does not include any reference to the territorial aspect of the promise given to Abraham and to his descendants.” - R. N. Longenecker, The Epistle to the Romans, NIGTC, 510.”

But this illustrates the divide quite well. What seems reasonable to one group looks pretty outlandish to the other.

Paul,

A few quick thoughts. I suppose we could all marshal commentators to sustain a point. Your references actually do little to support your view.

Per Murray: Of course the context is justification not Israel’s land grant. Paul is not interested in a restored physical homeland. The promise now extends to Jews and Gentiles without distinction in the Church.

Per Longenecker: You are correct. Paul “does not include any reference to the territorial aspect of the promise given to Abraham and to his descendants.” Here or anywhere else!

Paul shows that the promise to Abraham has been de-territorialized. Whether the “world” is a “worldwide family” (Morris, 206) or it summarizes the three key provisions of the promise to Abraham - descendants, land, medium of blessing (Mounce, Romans, 126; Moo, Romans 279), the physical land boundaries have been superseded. Jesus and the NT writers show little if any concern for land and I am not aware of any reference made in the NT concerning the land promise to Abraham.

Perhaps we can see a parallel with circumcision and the law. Both outward realties which had deeper meaning - circumcision is of the heart; the law given deeper heart meaning by Jesus (Matt. 5).

When we look at the book of Hebrews the promised rest is now found in Christ. Promised land is no longer the goal of God’s people (Burge, Whose Land? Whose Promise?, 179). Or as Brueggemann stated: “..a central symbol for the promise of the gospel is the land” (The Land, 179). What ethnic Jews sought in physical land, both believing Jews and Gentiles have found in Christ, our refuge, genuine “landedness.” The dispensational fixation on geography finds no resonance in the NT. I don’t find that outlandish. I do consider it wrong.

Steve

Yes, of course people will immediately argue over what “authorial intent” actually means. My suggestion for “authorial intent” wasn’t to necessarily be more precise, but to avoid unnecessary offense to covenant folks at the outset - so a decision can actually be started!

Telling somebody, “I read the text as it stands, but you spiritualize everything!” isn’t usually a good way to begin a conversation!

Tyler is a pastor in Olympia, WA and works in State government.

This is why the conversation, though not useless, can be unfruitful. I am sure that there are key things which Brothers Barkman and Davis want folks like me to “see”. It’s the same with me. For me the issues are 1. the OT is very clear and raises certain expectations. 2. Those expectations are raised by a God who makes oaths to perform them. 3. The covenant revelation in the OT is continuous and invariable. 4. God promises to perform His oaths with the strongest affirmations found in the whole Bible - Jer. 31:35f & 33:14ff. 5. The NT actually never plainly reverses these promises, neither could it without making God disingenuous. 6. The passages which my brothers claim reinterpret the OT neither address the covenant issues above nor do they have to be interpreted as if they did.

It is this matter of how to take God at His word if He can change it so radically that is the crux of the problem for me. I don’t think this problem is faced head-on by CT’s.

Obviously none of us will resolve the problems to everyone’s satisfaction.

Dr. Paul Henebury

I am Founder of Telos Ministries, and Senior Pastor at Agape Bible Church in N. Ca.

[Larry]From my experience, I that CT is equally committed to this concept, and perhaps even more so.

There are people like Peter Enns who flat out say that authorial intent of the OT doesn’t matter. I wonder if, in practice, that isn’t more prevalent that some might like to admit….

Interesting lead-in. Invoking Peter Enns to insinuate that orthodox Reformed theologians are closet liberals who deny Biblical inerrancy and the importance of OT authorial intent is like invoking Dr. David Jeremiah’s frantic middle-of-the-night call to John Hagee after the Brexit vote to establish that Dispensationalists take their lead from Mr. Hagee in ordering their Dispensational charts. After all, it was reported in The Babylonian Bee.

Peter Enns was forced out of Westminster Theological Seminary in 2008, and the Seminary retrenched in a more orthodox direction after Dr. Enns was found by the Seminary’s board to be outside the pale of orthodoxy on the doctrine of Biblical inerrancy. In 2011, his contract with The BioLogos Foundation was non-renewed because according to Dr. Enns it was going in a more conservative direction! BioLogos to this day affirms old-earth, evolutionary creationism or theistic evolution.

JSB

Invoking Peter Enns to insinuate that orthodox Reformed theologians are closet liberals who deny Biblical inerrancy and the importance of OT authorial intent

Do you think that’s a charitable reading of what I said? Do you honestly think you have correctly understood my intent?

I did not in any way insinuate that orthodox Reformed theologians are closet liberals who deny biblical inerrancy. All I suggested was that they underemphasize the importance of OT authorial intent. I honestly don’t think that is is dispute is it? Don’t a great many admit that the OT author could not have known the “fuller meaning” of his words and therefore we can’t limit meaning to authorial intent?

Yes, I believe that I rightly discerned the authorial intent. You do not actually believe that all “orthodox Reformed theologians are closet liberals who deny biblical inerrancy.” However, Peter Enns is a theological liberal in the broader Reformed community who does deny biblical inerrancy. You invoked his name for a reason, which was to tar orthodox Reformed theologians with the Peter Enns brush, creating the impression that his views are “more prevalent that some might like to admit.” Otherwise, you would not have mentioned his name. Who are these closet theologians who surreptiously hold to the views of Peter Enns?

I disagree with your assertion that orthodox Reformed theologians “underemphasize the importance of OT authorial intent.” Not only is that assertion in dispute generally but on this very page. G. N. Barkman above avers that Covenant Theologians are perhaps more committed to authorial intent than others are, and I agreed with him. Instead of invoking Peter Enns, interact with orthodox Reformed theologians and demonstrate that they “underemphasize the importance of OT authorial intent.” In fairness, you do make attempts at this, which deserve further exploration, which I will endeavor to do in the future.

JSB

Is it just me or is it ironic that in a discussion on authorial intent, you are telling another author what he meant (however, indelicately he might have put it)? As the one with the authorial intent in question, I can assure you that you missed the authorial intent. I invoked Enns’ name only to show that I was not making up a position as a straw man but was addressing a position that some actually hold. I then suggested that perhaps more do this kind of thing. In fact, what G. N. Barkman has said about the NT and OT meaning seems very similar to what Enns said. Yes, they hold very different positions on some other things, but that was never my point. If you want to make that point, I will gladly agree.

I recognize you and Bro Barkman say that CT are perhaps more committed to authorial intent than DT are. But that’s an assertion not an argument, and saying it doesn’t make it so. I can’t see the argument for it. Perhaps you could say they as committed, but more committed? I don’t see that. I suggested the opposite may in fact be true and for that I appeal to numerous places where people claim that the OT has a meaning that the OT author could not have known. We have seen it in this very discussion about the NC. I think everyone agrees that the Jeremiah’s words meant the ethnic Israelites. But a great many people think the meaning is broader than that, and maybe completely different than that. Or they think the land that the OT defines between the Euphrates and the river of Egypt, the land with the landmarks of the NC in Jer 31 is actually heaven, or spiritual rest, or some such. I don’t think we can entertain a serious argument that Moses or Jeremiah intended that. So therein is the discussion.

Larry, I believe that you have set forth excellent topics for discussion, and I hope to take up at least some of them as time allows. You are correct in saying that the statement, “Covenant Theologians are as, if not more, committed to authorial intent,” is an assertion. Likewise, the statement, “Dispensationalists are more commented to authorial intent,” is an assertion and not an argument. Which leads us nicely to the topics you have identified for discussion.

I do wonder what G. N. Barkman thinks about being compared to Peter Enns. Is he one of those “people like Peter Enns who flat out say that authorial intent of the OT doesn’t matter”? I am sure that you do not mean that. Which leads us nicely to the topics you have identified for discussion.

Thanks

JSB

To the first, yes both are assertions. I have offered arguments in support of my view of the first assertion. The only way to establish either assertion is, perhaps, to look at individual texts and then build a cumulative case.

To the second, to me, G. N. Barkman has come pretty close to saying that. I am not sure how he would explain it. Whether or not he would go as far as Enns does in that particular area, I do not know. I do not think G. N. Barkman embraces much else from Pete Enns.

Since you asked, I will go ahead and express my ignorance. Until the name, Peter Enns was brought up in this discussion, I had no idea who he was. I may have read something about him several years ago in connection to the Westminster Seminary controversy, but I had long forgotten his name, and have never been exposed to his teaching. I am certainly no disciple of Peter Enns.

My views on the interpretation of OT prophecy developed slowly over the years during the course of doing NT exposition for my own pulpit. It became apparent that few NT authors interpreted the OT in the manner I had been taught from my DT background. What do do? Do exegetical gymnastics with the NT to make it harmonize with my previous understanding of the OT? Or, revisit my previous interpretation of the OT in light of what I was discovering in the NT? I was more or less pulled into a new sympathy for CT by what I considered to be the demands of the NT. Did I embrace CT? Not fully. I have some of the same problems with CT that DT’s allude to on SI. I see weakness in the Covenant of Works, Covenant of Grace foundation, though I also see some merit in this apporach. The Federal Headship of Adam parallel to the Federal Headship of Christ seems beyond dispute. If that’s what one means by Covenant Theology, count me in.

It seems problematic to me to build a defense for DT upon what we believe the average OT saint would have understood the OT to mean. In the first place, we can never fully know. In the second, we Do know that few, if any first century saints understood the OT correctly. They had to be corrected by Christ and the ongoing illumination of the Holy Spirit. I cannot shake myself from the opinion that NT inerpretation of the OT must be given more weight than my un-inspired OT interpreation, regardless of how clear the original words may seem to me. I could be mistaken. I have been many times, and undoubtedly still am in who know how many areas? But Christ and the Apostles cannot be mistaken. I take them as my guide to endeavoring to understand the divinely intended meaning of the OT. I am happy to yield my first impressions of the OT to their infallible understanding.

G. N. Barkman

Thank you for taking the time to briefly explain your position in regard to OT authorial intent. I respect your position and was sure that you had respect for the authorial intent of the OT, just from a broader perspective than Brother Larry. In any event, your position would be much closer to Larry’s than to Peter Enns. Greg Beale has summarized Enns’ position as follows: “he holds various significant narratives in Genesis to be “myth” according to its classic definition, and that he acknowledges that the biblical writers mistakenly thought such “myths” corresponded to real past reality.” (http://www.reformation21.org/miscellaneous/a-surrejoinder-to-peter-enns-response-to-g-k-beales-jets-review-article-of-his-b.php).

JSB

I cannot shake myself from the opinion that NT inerpretation of the OT must be given more weight than my un-inspired OT interpreation, regardless of how clear the original words may seem to me. I could be mistaken. I have been many times, and undoubtedly still am in who know how many areas? But Christ and the Apostles cannot be mistaken. I take them as my guide to endeavoring to understand the divinely intended meaning of the OT. I am happy to yield my first impressions of the OT to their infallible understanding.

This I agree with wholeheartedly. But it does not really answer the question in at least two ways:

First, it seems obvious that many NT uses of the OT do not intend to give an interpretation at all. Thus, they are not guide for interpretation.

Second, it doesn’t help us with OT passages that the NT does not interpret. There, we are back to the issue of authority: On what authority can I say that the text of Scripture means something? IMO, I can only say that by exegeting the words of the text. The call to belief and obedience must arise out of the text, not out of the preacher’s imagination. And that’s my concern. It seems that a lot of OT meaning is being generated by the preacher’s imagination, not by exegesis.

How would you respond to/interact with these statements?

- A Christian understanding of the OT should begin with what God revealed to the Apostles and what they model for us: the centrality of the death and resurrection of Christ for OT interpretation.

- What if biblical interpretation is not guided so much by method but by an intuitive, Spirit-led engagement of Scripture with the anchor being not what the author intended but by how Christ gives the OT its final coherence?

- It is the conviction of the Apostles that the eschaton had come in Christ that drove them back to see where and how their Scripture spoke of him. And this was not a matter of grammatical-historical exegesis but of a Christ-driven hermeneutic. The term I prefer to use to describe this hermeneutic is Christotelic … for the church, the OT does not exist on its own, in isolation from the completion of the OT story in the death and resurrection of Christ. The OT is a story that is going somewhere, which is what the Apostles are at great pains to show. It is the OT as a whole, particularly in its grand themes, that finds its telos, its completion, in Christ.

- It is precisely because they were the Apostles, to whom the inscripturation of the New Testament had been entrusted, that we should follow them. We follow them in their teaching, so why not in their hermeneutic?

Larry, that’s exactly what I’m trying to say, and exactly what I’m trying to do. If we start with the NT citations of OT Scripture that do offer interpretation, we get a glimpse into how Christ and the Apostles understood the OT. Obviously they didn’t deal with all the OT. If they did, the NT would have to be bigger than the OT. But let’s begin with the Scriptures they did interpret, and see what insight that gives us. It won’t explain every OT text, but it just might start us on a path that allows us to see the OT in a fresh light. As long as we are locked into a hermeneutic that does not allow us to accept what the inspired NT writers revealed, we will be blind to their inspired insights. The question of hermeneutics is at the heart of this discussion. Do we begin with our rules of hermeneutics before we open Scripture, or do we study Scripture to discover rules of hermeneutics used by Christ and the Apostles?

G. N. Barkman

Discussion