Baptism in History, Part 1

The very early tradition of the Christian church

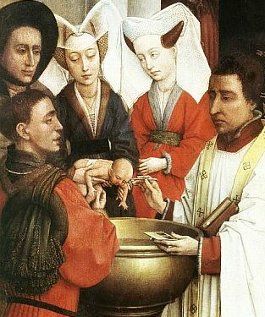

An examination of baptism in the first few centuries of the church brings up many questions. The most important of these is, what did the Apostles teach in Scripture? But both paedobaptists1 and credobaptists can easily read Scripture in light of their own tradition. This series focuses on history. What was the very early tradition of the Christian church? Part 1 focuses on the period closely following the completion of Scripture. In this period, each writer has either first-hand or second-hand exposure to an Apostle. Part 2 will explore the next period: what was taught and practiced between the very early church era and Augustine? Part three will focus on Augustine: what was Augustine’s contribution to the doctrine of baptism?

Eusebius: “brought up” then baptized

What did those with close exposure to the Apostles teach? In The History of the Church, written in the 4th century, Eusebius relates this story:

When the tyrant was dead [Diocletian, A.D 96], and John [the Apostle]…used to go when asked…sometimes to appoint bishops, sometimes to organize whole churches, sometimes to ordain one person of those pointed out by the Spirit…. [He] finally looked at the bishop and indicating a youngster he had noticed, of excellent physique, attractive appearance, and ardent spirit, he said, ‘I leave this young man in your keeping’…. [T]he bishop accepted him and promised everything…the cleric took home the youngster entrusted to his care, brought him up…and finally gave him the grace of baptism.2

If the implications of the details of the story are correct, this boy was selected by John from those in the church. He was in this church, noticed (presumably pointed out by the Holy Spirit) by the Apostle John and raised by a bishop who had some relationship with the Apostle. Even though he was present in the church and raised on John’s order, he received baptism only after he was “brought up.”

Aristides: converting the children of Christians

Turning to the leaders in the early church, the 2nd century Aristides defended Christians whose “servants or…children if any of them have any, they persuade them to become Christians for the love that they have towards them; and when they have become so, they call them without distinction brethren.”3 Aristides implies an answer to my first theological question: “Should infants of believing parents be considered part of the covenant community?” They were not. Instead, the church sought the conversion of the children of Christians. After that, they were treated as part of the Christian community. Paedobaptists stand, in part, on the idea that the promise is for you and your children. It is important to them that children are part of the Christian community by default. But the words of Aristides suggest that he stood on the idea that the Christian community was defined by faith, which is consistent with credobaptist teaching.

Didache: fasting precedes baptism

The Teachings of the Twelve Apostles, or Didache, was written at the end of the 1st or the beginning of the 2nd century. It says of baptism,

[T]his is how you shall baptize…. baptize in living water in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit…. before the Baptism, let him that baptizes and him that is baptized fast, and any others also who are able; And you shall order him that is baptized to fast a day or two before.4

No instructions are given for infant baptism. Instead, it is assumed that the candidates for baptism are able to take orders to fast for one or two days. The instructions make more sense if credobaptism was contemplated by the writer, though that isn’t certain. It is possible that the reader was expected to apply the fast only to adults. If infant baptisms had been in view, we would expect to find instructions here. The writers of the Didache made the effort to provide instructions for temperature (cold) and type of water (moving). But in the matter of personal preparation they only bothered to provide instructions for adults.

Justin: knowledge and choice

Justin Martyr’s First Apology (circa A.D. 150) includes a description of baptism:

All then who are persuaded, and believe, that the things which are taught and affirmed by us are true; and who promise to be able to live accordingly; are taught to pray, and beg God with fasting, to grant them forgiveness of their former sins; and we pray and fast with them…. [A]nd after the same manner of regeneration as we also were regenerated ourselves, they are regenerated…[receiving] the washing of water.5

This was the pattern in the church. People were taught the gospel. They promised to live accordingly and were trained to do so. When they had done all this, they were baptized. This is credobaptism. Our brothers who practice and teach baptism of infants have two objections. First, while Justin does not name infants, they are not specifically excluded. Second, the church at that time was primarily in a missionary mode. Most baptismal candidates were adults who were coming to the faith and not the children of church members. “Missionary mode” might explain Justin’s focus on what was common: adults. However, Justin also cites what he says are apostolic reasons for how they practiced baptism:

And we have received the following reason from the Apostles for so doing; since we were ignorant of our first birth…in order that we might not remain the children of necessity and ignorance, but of choice, and of knowledge; and that we might obtain remission of the sins we had formerly committed; in the water, there is called over him who chooses the new birth, and repents of his sins, the name of God the Father and Lord of all things; and calling Him by this name alone, we bring the person to be washed to the laver.6

Knowledge and choice were important. They were the “reason” for how the church practiced baptism. Justin said the second birth should be contrasted with the first. The contrast was between ignorance with the first birth and choice and knowledge with the second birth. Baptism was for those who chose the new birth, repented of sins, and called on God. Justin’s point that the first birth and baptism are distinct in regard to knowledge and assent doesn’t make sense if he knew that, for some Christians, they were not distinct and both births occurred in the ignorance of infancy. Further, Justin claims apostolic tradition for this. His account seems to demand faith and exclude infant baptism.

Irenaeus: Christ saving infants

Irenaeus’ perspective is weighty because he knew Polycarp, who knew John the Apostle. He wrote Against Heresies in the late 2nd century to oppose the Gnostics who denied that Christ was ever an infant:

He came to save all by Himself: all, I mean, who through Him are newborn unto God: infants, and little ones, and boys, and youths, and elder men. Therefore He passed through every age, being first made an infant unto infants, to sanctify infants.7

This passage is taken by some to mean that Irenaeus believed in the baptism of infants. But does Irenaeus intend to equate the new birth with baptism here? Did Irenaeus generally believe the two were same? Elsewhere, Irenaeus said, “And again giving His disciples power to regenerate into God He said unto them, ‘Go and teach all nations baptizing them in the Name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Ghost.’”8 He also referred to “the denying of Baptism, our new Birth unto God, and to the rejection of the whole Faith.”9

Irenaeus did equate baptism with the new birth in some sense. If he had that view in mind in his statement about the new birth of infants, we should conclude that he is referring to the baptism of infants. But both sides of this debate can easily read the statement in light of their tradition. Baptists read him as saying that infants who die are saved, but not necessarily baptized.

In Fragment 34, Irenaeus says:

[W]e are made clean from our old transgressions by means of the sacred water and the invocation of the Lord. We are thus spiritually regenerated as newborn infants, even as the Lord has declared: ‘Except a man be born again through water and the Spirit, he shall not enter into the kingdom of heaven.’”10

Does Irenaeus mean to say that “while” newborn infants we are regenerated? Or does he mean that we adults are regenerated and born-again as new-born infant Christians? It appears that Iranaeus is open to multiple interpretations.

Hippolytus: others speak for converts

In the early 3rd century Hippolytus described the methods for baptism in Apostolic Tradition: “They who are to be [baptized] shall be chosen after their lives have been examined: whether they have…been active in well-doing.”11 Their “sponsors” testified to this.

[A]s the day of their baptism draws near, the bishop himself” must “be personally assured of their purity.

Then those who are set apart for baptism shall be instructed to bathe and free themselves from impurity and wash themselves on Thursday…. They who are to be baptized shall fast on Friday…. They shall spend all that night in vigil, listening to reading and instruction.12

Only believing applicants can fulfill these requirements. They must demonstrate good works and purity, fast, read Scripture, and hear instruction. But Hippolytus continued, “And first baptize the little ones; if they can speak for themselves, they shall do so; if not, their parents or other relatives shall speak for them. Then baptize the men, and last of all the women…”

These words are often cited as evidence of infant baptism. That interpretation comes easily to the minds of those accustomed to baptizing infants. However, leaders with experience interviewing and baptizing believing children tend to read this differently. Some children can speak for themselves. Others, while able to answer to their parents and friends, are too frightened to speak before the body of believers. This scenario is common. Their parents answer “for them” to the body. This reading also seems to fit better with the idea of “answering for” someone else. Paul demanded the opportunity to “answer for himself” in court (Acts 25:16). Hippolytus uses a list of questions of faith which must be answered. Anyone attempting to answer for another should know what that person believes.

Summary

Hippolytus leaned towards credobaptism. The Didache seems to assume credobaptism, but does not explicitly defend it. The cleric friend of John the Apostle practiced credobaptism. Justin Martyr argued positively that baptism is distinct from physical birth in that it is done with knowledge and assent. Aristides was inclined toward faith as the basis for inclusion in the Christian community, which is a basis for credobaptism. Irenaeus does not clearly advocate one position or the other (though he seems more likely to have been a paedo-baptist).

Since church was in more of a missionary mode in those times, most new believers were adults who were not from believing families. Can this explain why Hippolytus and the Didache, though alleged to be in favor of infant baptism, spoke of baptism with requirements that only adults could fulfill? Perhaps. But even in those days Christians had children. The “missionary mode” concept cannot explain Justin Martyr, because he doesn’t just ignore babies—he argues that the baptized ones should be aware as opposed to infantile. It appears that the very early church was credobaptist.

Notes

1 The term “paedobaptist” derives from the Greek pais, meaning child or infant. Here is refers to infant baptism. “Credobaptist” derives from the Latin term credo, “I believe,” and refers to believer’s baptism.

2 The History of the Church, Eusebius, Trans. by G.A. Williamson, Penguin Books, London, 1965, pp. 83-84.

3 The Apology of Aristides, Ed. and Trans. by J. Rendel Harris, M.A., Cambridge University Press, 1893, p. 49.

4 Didache - The Teaching of the Lord by the Twelve Apostles to the Gentiles. [Online] Available from http://www.ccel.org/ccel/richardson/fathers.viii.i.iii.html. Accessed 5 July 2010.

5 First Apology 61, The Works Now Extant of Justin the Martyr, Oxford, London 1861, p. 46.

6 Ibid., p. 47.

7 Against Heresies, Book IV, Ch. 22.4, “Christ Blessed Every Age by Sharing It,” from Five Books of S. Irenaeus, Bishop of Lyon, Against Heresies, Trans. The Rev. John Keble, M.A., 1872.

8 Ibid., Book 3, Ch. 17.1.

9 Ibid., Book 1, Ch. 21.1.

10 Fragment 34, Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers Vol. 1, Edited by Philip Schaff, D.D., LL.D., Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., Grand Rapids. [Online] Available from http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/anf01.ix.viii.xxxiv.html. Accessed 5 July 2010.

11 The Apostolic Tradition of Hippolytus, translated by Burton Scott Easton, Cambridge University Press, New York, 1934, p. 44.

12 Ibid.

Dan Miller is an ophthalmologist in Cedar Falls, Iowa. He is a husband, father, youth-worker, and part-time student.

- 1384 views

I am lookng forward to your future posts.

Dick Dayton

I hope you do.

Thought you may want to see it to help with your future articles.

Joshua, I found a couple immersion type references, but it wasn’t my focus. I’m in Chicago this weekend. I’ll check my notes when I get home.

The Puritans objected:

1. No Scripture.

No duh. I’m confident that both sides can read Scripture consistently with their own tradition. I don’t plan to address that.

2. No Tert. No Cip. No Aug.

Parts 2&3

These guys probably WAAAY know more church history than I. If they read here, I would say this to them.

1- I found this study a little frustrating. Tons of bias (no doubt on my part, as well). So Tertullian argues against paedB. Credos say, “See, early church guy who’s a credo.” Paedos say, “If he’s arguing that way, he must have been up against a world of Paedos.” I don’t see him as convincing either way.

2. What about Justin Martyr? He seems to me to be anti-Paedobaptist.

3. At least you didn’t say, “What about Origen.” I don’t think anyone would pick him for their theological softball team.

My first methodological concern is that you seem to assume that there really is such a thing as “the” early church. If the last 250 years of scholarly research has demonstrated anything, it’s the great diversity in doctrine in the church from the earliest days. Because of views that developed fairly early on about the immutability of doctrine and apostolic succession (variously understood), the church had trouble acknowledging this diversity. An example is the extreme expurgation of Origen found in Rufinus’ Latin edition, or how earlier Church Fathers are made to fit the views of mature Homoousianism. Frankly, even the Nicene Creed didn’t mean everything that two generations later asserted it to mean. My point here is that it’s quite possible that the very early church (a period you don’t define) already had divergent baptismal practices. Maybe Justin Martyr was anti-pedobaptist. Maybe Irenaeus was pedobaptist.

That said, I think your interpretation of Irenaeus is highly implausible. In the light of Irenaeus’ recapitulation theology of salvation, it’s hard to read him in a “Baptist” way. There’s little doubt that Irenaeus (or any other Father who uses the same language) meant anything other than baptismal regeneration by “newborn unto God” (which, if I remember the Greek text correctly, actually uses a form of the word “regenerate”), and he specifically includes infants in that class of people. In Irenaeus’ theology, there’s no indication that there’s any other way to be reborn unto God. The relevance of Fragment 34, which you quote, is to show that Irenaeus believes that John 3:5 teaches baptism as the only way to be “born again.” It’s not that hard to put together. You should also ask yourself, how did other Fathers read and understand Irenaeus’ theology?

Concerning Eusebius, I have two problems. First, by way of method, Eusebius is a 4th century writer, and as such, is not really pertinent to the period in your article. Simply because he attempts to relate a story from the 1st century doesn’t mean that it has a shred of credibility, especially that far removed and, well, from Eusebius. Second, if we were to grant the story is true as told, the “young man” isn’t a child. I couldn’t get access to a Greek text, but based on my reading in Schaff, that term is usually used for an adulescent, perhaps a man in his early twenties. In any case, the description “of a powerful physique” surely points toward puberty or older. There is no indication that he was born the son of Christian parents. In fact, it seems likely that he was recently introduced to the church, because he had not undergone the catechetical training necessary for baptism.

I think your explanation of the Didache is perhaps the weakest part of your argument. It seems as though you are unfamiliar with the genre. The Didache is widely understood to be a catachetical instruction book. It’s a discipleship manual, if you will, for those in charge of bringing the catechumens into full communion. The book is divided into two parts: The “two ways,” the catechetical material that prepared the catechumens for baptism, and the instructions for how to perform the rite. There’s simply no call for the book to mention infants.

Additionally, I find your inclusion of Hippolytus suspect. Hippolytus is contemporaneous ei perhaps even a bit later than Tertullian. In any case, your conclusion that he “leaned toward credobaptism” is silly. It implies that he considered two different theological paradigms, was conflicted toward them, but generally stuck to one side. Perhaps you meant to say that the evidence in Hippolytus inclines us to conclude that he was credobaptist?

In sum, I find not only that I disagree with certain of your statements, but that most of your research suffers from fatal methodological flaws: assumption of homogeneity, refusal to interpret words and phrases within the greater construct of an individual’s theology, ignoring the genre of documents, and including materials arbitrarily. It’s difficult to interact with a piece of research that doesn’t proceed by conventional historical methods or make a case for its own method. It looks rather like you just took a book of quotes, picked out certain ones, and strung them together.

My Blog: http://dearreaderblog.com

Cor meum tibi offero Domine prompte et sincere. ~ John Calvin

I’m not sure I have a misunderstanding of the Didache. I understood it to be a book considered valuable in the life of the church in general.

I also don’t follow your argument that if it is catechetical, then there would not be a need to include infant baptism instructions. IF the writers were paedobaptists, it seems they would especially need to include that. Some new believers would have infant children in their households. This may simply be an issue that each will perceive in accordance with his own biases. To me, it seems like it would be a glaring omission.

In my paper, I said Didache leans toward credo-. That is not a claim of conclusive proof and I didn’t intend it to be. Perhaps I should also say it can be read as consistent with either practice and that it seems most consistent with credo-b. What it comes down to is each reader’s estimation of the likelihood that a paedoB writer would leave out instructions for infants.

Regarding Irenaeus, I will also grant that he has been interpreted as you say. I should have been clearer that both of the quotes I gave from him are commonly used to promote paedobaptism. My only point was that for it to be sure that Irenaeus meant what you say he meant, we must say that he accepted baptismal regeneration AND that he intended that equation in that instance. The first is likely; the second? Maybe. So you may be altogether right on him. My intention was to say that he is not iron-clad on the issue and that an alternative view is possible.

Besides, the church now rejects baptismal regeneration. So it seems that Irenaeus’s conclusion is accepted, even though his reasoning is rejected.

You also say I should ask how other fathers understood Irenaeus. Maybe. But as our discussion and the books I’ve read demonstrate, an unbiased viewpoint is not easy to accomplish. Each reads in light of his own beliefs. Given the direction the church took over the next few hundred years, I’m guessing it will be paedo-baptist fathers that will be interpreting Irenaues for us. (I hope that didn’t sound too snide.)

In reading your comments on Hippolytus, I think I should have said that his words seem most consistent with credo-baptism. I get what you mean about leaning.

I’m interested in what you understand about Justin Martyr. He seems to me to very overtly argue antipaedobaptism. His argument concerning the distinction between the first and second birth has not received a lot of attention, as far as I can tell. Do you know of comments made by theologians on that section?

Re: homogeneity vs. “great diversity in doctrine in the church from the earliest days,” you anticipate Part 4. Did I say I thought there was homogeneity? Perhaps I did. I guess I am biased in that direction and it keeps coming out.

The Didache was far more than a catechumen book, designed to bring catechumens into full communion. The second half of the Didache is widely recognized as a manual of church order. It instructed who was to be accepted as a teacher in a congregation and who was not; how long they may stay in one place, etc. It instructed congregations to elect their own bishops and deacons. It encourages congregations to gather frequently. This is not primarily information for people being brought into the Christian faith, anymore than 1 John - with all its warnings about false teachers - was written for people being introduced to the faith. The Didache was written for already existing congregations. It was, in a sense (probably unwittingly), filling a gap until all Christian congregations could be supplied with a complete New Testament. The Didache’s instructions about baptism fall into the section that is a manual for church order.

But the idea that the genre of the Didache illiminates the need of explaining that infants are candidates for baptism is anything but convincing. The Didache explains in detail how baptism is to be conducted. Why wouldn’t it name anything about infants being subjects? If you are right, I think that most people reading your post don’t see your point. Perhaps you could substantiate this assertion.

The Didache states, “Also, you must instruct the one who is to be baptized to fast for one or two days beforehand.” No Christian in his right mind in that day would have required forcing an infant to fast for one or two days before it was baptized. Clearly, the Didache had only confessors and no infants in view as candidates for baptism.

Jeff Brown

Dan,

I was overly harsh in my evaluation earlier. Something I like about your article is that it considers the question of baptism from multiple angles: how did the Church regard their children, how did they view regeneration, etc. Your appeal to Justin Martyr reflects this, and I think it has merit. I don’t remember very much attention being given to that passage, though, and perhaps it deserves more scrutiny.

There is a general trend of argumentation that I didn’t mention earlier, though, that I think is problematic. It is natural for Baptists to think in this fashion: Baptism requires A, B, and C; infants cannot perform A, B, and C; therefore, infants cannot be baptized. Reading such thoughts back into Hippolytus seems unpersuasive. If we fast-forward to, say, Augustine, we find that the requirements for adult baptism are still in place, and probably even more complex; yet, everyone is baptizing infants. The Church at that time perceived that the one case was not applicable to the other. Since that was clearly the case in the 5th century, and there is no evidence of discontinuity, there is no reason to believe that could not have been the case in the third century. Even Tertullian, the only clear anti-pedobaptist from Hippolytus’ period, does not make that argument. We have no reason to believe that Hippolytus, then, would have understood his conditions as in any way relevant to infant baptism. There were pedobaptists at the time of Hippolytus, and had he been anti-pedobaptist, surely he passed up an opportunity to give guidance in that area.

In fact, that’s sort of the rub, isn’t it? Other than Tertullian, there isn’t anybody speaking out against infant baptism, and even Tertullian doesn’t deploy the two arguments one would expect if infant baptism was a novel trend: 1) that it was indeed a novelty; when does any Church Father hesitate to use this argument, even when it’s not true? 2) That infants don’t meet the qualifications for baptism. I think you’re backing yourself into a corner. The later you push the “origin” of infant baptism, the more difficult it becomes to account for its widespread acceptance in the 3rd century. Even if your conclusion is that the very early (1st century) church only baptized believers, I think a stronger approach would be to admit more heterogeneity (so you can deal with people like Irenaeus) and put the rise of infant baptism very early on, which would account for the lack of protest and reaction in the documentary evidence.

I don’t know the extent of your familiarity with the secondary literature, but a few great small books are Joachim Jeremias’ (pedo) and Kurt Aland’s (anti-pedo) book war from the 1960’s. I’m not aware that the state of scholarship has advanced significantly since then.

My Blog: http://dearreaderblog.com

Cor meum tibi offero Domine prompte et sincere. ~ John Calvin

[Charlie] I was overly harsh in my evaluation earlier.No problem. If I didn’t want peer review, I wouldn’t have posted it here. Actually, it’s a stretch to call this peer review, since you probably know quite a bit more about this subject that I do.

Re: Tertullian,

Your 1) is a legitimate question. From the way Tertullian speaks, it seems that infant baptism was fairly common. I think I address your 2) in Part 2.

We all begin with presuppositions when tackling a subject. One could just as easily say, not only that Baptists think a certain way, but that Catholics, Lutherans, and Presbyterians think a certain way about this subject when approaching the evidence. It is undeniable that Tertullian is the first in literature to say anything critical about infant baptism. He is the first to say anything at all about infant baptism. That leaves the burden of proof on the side of those who contend that infant baptism was always a regular practice. I believe I am correct in saying that the first mention of any baptism of infants or young children occurs in inscriptions (late 2nd century), and interestingly, rarely even using the word “baptism.” Instead, the words “received grace,” or “neophyte,” are used to declare the faith (and baptism) of some chldren. Very few Christian graves of children for this time period, however, make any such references. But infant baptism is not in any extant documents giving any instruction until Tertullian, and his was to instruct against it.

Jeremias and Aland present superb scholarship, but have been surpassed now. One of the leading Church historians in North America is Everett Ferguson. If you do any significant amount of study on the doctrine of the Church in Second Century of Christianity, you will not be able to avoid encountering his research. Last year he published Baptism in the Early Church: History, Theology, and Liturgy in the First Five Centuries, Eerdmans. Like most of what Ferguson writes, it is massive and thorough, over 900pp. in length. He includes both all literature and all inscriptions available from the time period that deal with the subject.

Dan,

You are conducting a worthy exercise.

Jeff Brown

[Dick Dayton] Dan, This is a great post, and shows that you have done some serious study in the original sources. Thanks for all your work. At the Iowa Association Of Regular Baptist Churches springn conference this year, Dr. Paul Hartog invested some time helping us with Baptist history. The messages were recorded, and were posted on the Ankeny Baptist Church web site. Dr. Hartog pointed out that those who called themselves “Baptist” came from some varied backgrounds, and things in history are not always as neat and compartmentalized as we would like to think.There seems to be some problem with their website.

I am lookng forward to your future posts.

Discussion