Theology Thursday - J.C. Ryle on Simple Preaching

Image

Ryle, the great Anglican bishop, offers some more advice for preachers:1

The third hint I would offer, if you wish to attain simplicity in preaching, is this—Take care to aim at a SIMPLE style of composition. I will try to illustrate what I mean.

If you take up the sermons preached by that great and wonderful man Dr. Chalmers, you can hardly fail to see what an enormous number of lines you meet with without coming to a full stop. This I regard as a great mistake. It may suit Scotland, but it will never do for England. If you would attain a simple style of composition, beware of writing many lines without coming to a pause, and so allowing the minds of your hearers to take breath.

Beware of colons and semicolons. Stick to commas and full stops, and take care to write as if you were asthmatical or short of breath. Never write or speak very long sentences or long paragraphs. Use stops frequently, and start again—and the oftener you do this, the more likely you are to attain a simple style of composition. Enormous sentences full of colons, semicolons, and parentheses, with paragraphs of two or three pages’ length, are utterly fatal to simplicity.

We should bear in mind that preachers have to do with hearers and not readers, and that what will “read” well will not always “speak” well. A reader of English can always help himself by looking back a few lines and refreshing his mind. A hearer of English hears once for all, and if he loses the thread of your sermon in a long involved sentence, he very likely never finds it again.

Again, simplicity in your style of composition depends very much upon the proper use of proverbs and pointed sentences. This is of vast importance. Here, I think, is the value of much that you find in Matthew Henry’s commentary, and Bishop Hall’s Contemplations. There are some good sayings of this sort in a book not known so well as it should be, called ‘Papers on Preaching’. Take a few examples of what I mean:

- “What we weave in time—we wear in eternity.”

- “Hell is paved with good intentions.”

- “Sin forsaken, is one of the best evidences of sin forgiven.”

- “It matters little how we die—but it matters much how we live.”

- “Meddle with no man’s person—but spare no man’s sin.”

- “The street is soon clean when every one sweeps before his own door.”

- “Lying rides on debt’s back—it is hard for an empty bag to stand upright.”

- “He who begins with prayer—will end with praise”

- “All is not gold that glitters.”

- “In religion, as in business—there are no gains without pains.”

- “In the Bible there are shallows where a lamb can wade—and depths where an elephant must swim.”

- “One thief on the cross was saved, that none should despair—and only one, that none should presume.”

Proverbial, pointed, and antithetical sayings of this kind give wonderful perspicuousness and force to a sermon. Labor to store your minds with them. Use them judiciously, and especially at the end of paragraphs, and you will find them an immense help to the attainment of a simple style of composition. But of long, involved, complicated sentences—always beware!

Notes

1 J.C. Ryle, Simplicity in Preaching: A Few Short Hints on a Great Subject (London, UK: William, Hunt and Co., 1882), 26-29.

Tyler Robbins 2016 v2

Tyler Robbins is a bi-vocational pastor at Sleater Kinney Road Baptist Church, in Olympia WA. He also works in State government. He blogs as the Eccentric Fundamentalist.

- 84 views

This is part of the tradeoffs built into manuscripting. There are benefits to manuscripting sermons, but also some liabilities. We tend not to speak conversationally the way we write, so the manuscripted sermon tends to lose in the rapport department. Audiences feel less like “this is a real person talking to me personally.” And there is less responsiveness to what’s happening live in the room. …and more.

Well studied texts preached used well prepared notes and delivered extemporaneously is best for most audiences.

I do recall, though, a couple of preachers over the years who used “partial manuscripting” very effectively. So I’ve tried to do that at times in my own preaching: occasionally writing out a full paragraph to read at the right moment. Mostly though, this hasn’t worked well for me. They usually end up unread because when the intended moment in the sermon came, reading it didn’t feel like the right thing to do. There’s a rhythm to keeping audiences engaged, and I don’t personally think it’s good to let prior plans spoil that.

Views expressed are always my own and not my employer's, my church's, my family's, my neighbors', or my pets'. The house plants have authorized me to speak for them, however, and they always agree with me.

To Aaron’s point, one of the hardest things to do when writing a play/screenplay is to make the dialogue sound natural. That’s a specific skill set that many writers do not have, which is why only a few ever make it as a screenwriter.

For what it’s worth, I manuscript. And then, because of my theatre background, I edit on my feet. In other words, I stand at the pulpit and read it aloud so that I can hear how the words and phrases hit my ears. I understand that since I don’t preach every Sunday, that’s a luxury that many who preach do not have.

As far as “Audiences feel less like ‘this is a real person talking to me personally’,” I’m thankful for my acting training, especially my training in improvisation. I know that it makes some people very uncomfortable to think about a preacher using acting skills in the pulpit, but I believe with every ounce of my being that not only is it appropriate, it’s a helpful and highly useful tool. The BJU preacher boys who were in my acting and speech classes with me are some of the best preachers that I’ve heard. My point - preachers should consider taking an improvisation class or two.

There’s a lot of overlap between the skills of drama/stage and the skills of rhetoric. Among other things, both involve heightened awareness of how we look and sound to audiences and shaping delivery accordingly.

I could not fit in any courses in acting due to my major/minor mix, but a bit of time as an “extra” in a play or two, and one stint in opera chorus deepened my appreciation for the art.

Views expressed are always my own and not my employer's, my church's, my family's, my neighbors', or my pets'. The house plants have authorized me to speak for them, however, and they always agree with me.

While topical preaching has its place, I love good expositional preaching. My peeve is that too many sermons seem to be the product of academic research where information from commentaries is organized and presented. I love to hear men exposit and apply the text as opposed to sermons constructed from material derived from books about the text. It can be and is done effectively from or manuscripts or near-manuscript outlines and that requires being “possessed by the text” as well as developing pulpit speaking skills.

I hear here are well-known expositors who spend the majority of their preparation in the text with minmal use of commentaries.

"Some things are of that nature as to make one's fancy chuckle, while his heart doth ache." John Bunyan

Seems to me I remember an actor who did pretty well in politics because he paid attention to the significance of how he phrased things. We might do well to remember that from the pulpit—or in my case, from the Sunday School room—as well.

I really appreciate what Ron notes as well. There are, in my view, two big errors that fundagelical preachers and teachers fall into. The first is to fail to exegete the text much at all, choosing rather to use it as a springboard for what they really want to talk about. I see this a lot in Sunday School materials, and the logical and exegetical jumps are often quite Beamonesque. (think long jump in 1968 Olympics)

The second is a variant of the first, to exegete primarily using the commentary. While I consult commentaries to get a feel for whether I’m missing something big, I can think of two reasons not to give a high place to the commentary in a lesson or sermon. First, the commentator doesn’t know the lay of the land—it will be needlessly academic. Second, part of the magic of teaching, or giving a sermon, is in demonstrating to the hearers how to exegete for themselves. Going directly to a commentary shortcuts that process.

Aspiring to be a stick in the mud.

I’ve often wondered where that commentary habit comes from. Interpretive resources are generally the last place I go in sermon prep. Going to them too early in the process tends to (a) information overload and (b) a pulling of the mind into academic rather than homiletical/pastoral concerns.

Context is 90% of Bible study and any kind of pulpit work prep.

Views expressed are always my own and not my employer's, my church's, my family's, my neighbors', or my pets'. The house plants have authorized me to speak for them, however, and they always agree with me.

I’ve interviewed a lot of Bible college grads for a youth pastor position at my church in the past year, and I’ve made a habit of asking them two questions to get an idea of how they think. First, what are their favorite references, and second, what courses they would take if money and time no limitation. The scary thing is that the answers are always the same. The favorite reference is always a commentary, and the second is always some practical course. Nobody ever says “I’d love to finally learn Hebrew”, or points to a favorite Greek lexicon or systematic theology.

I visited the websites of their Bible colleges to see what the curriculum looked like, and it started to make sense. No language study, not much in terms of exegesis, few or no electives…they’re using the commentaries because it’s the best tool they’ve been given.

Aspiring to be a stick in the mud.

The link is for assistant pastor major, but given that most assistants go on to become pastors, the absence of original language or Bible Interpretation is surprising.

I’d have to do some digging to be sure, but I believe I did four semesters of Greek at BJU. It was certainly not less than two.

… in their defense, we could say that’s what seminary is for, not undergrad. But I really do think BA and BS degrees for these roles should have a biblical languages overview and a couple of semesters of Bible Interpretation.

Views expressed are always my own and not my employer's, my church's, my family's, my neighbors', or my pets'. The house plants have authorized me to speak for them, however, and they always agree with me.

….was that it was pretty consistent wherever I looked. Now I’ll grant that it might have looked quite different if we’d tried to get guys with an MDIV, but among the Bible college guys, it was a lot of topical/book study stuff.

And the scariest thing was that even beyond the languages thing—OK, I’m a language junkie but it shouldn’t be my only thing—I’m not seeing things like stated classes in exegesis, hermeneutics, and the like. So my bet is a lot of the “commentary junkie” stuff we’re seeing will correlate really well with Bible college grads and not guys with an MDIV.

Aspiring to be a stick in the mud.

It was probably four semester of Greek at BJU. That’s what I took as an undergrad working on a BA in Bible. I was in a car accident my 3rd semester, spent several days in the hospital, and got behind in my Greek class. (It was brutal—five hours of classes per week, even though it was rated a three hour course.) I passed, but with a low grade. (Probably a C. I really don’t remember.) I DO remember that I knew I had not mastered the material well enough to go on to my 4th semester, so I elected to repeat the class. Result, I made a decent grade and went on to complete four full semesters. So in my case, I had 5 semesters of NT Greek as an undergrad. I thank God for the rigorous academic standards in my BJA and BJU education.

G. N. Barkman

Hands down: my Greek classes.

Dr. Rodney Decker instilled in me a love for my Greek NT and taught me how not to misuse the original languages in my exegesis and in my preaching. It resulted in being able to spot the misuse of the original languages in the preaching and writing of others. It also opened my world to being able to interact with exegetical commentaries.

As for preaching, I usually preach from an outline.

I do full manuscripts, but I organize it into bullet form, and I don’t read them when I preach. I glance down regularly to catch my bearings, but I don’t read the manuscript at all. The act of writing the manuscript out beforehand structures the info in my head, so I can basically run with it on Sunday mornings.

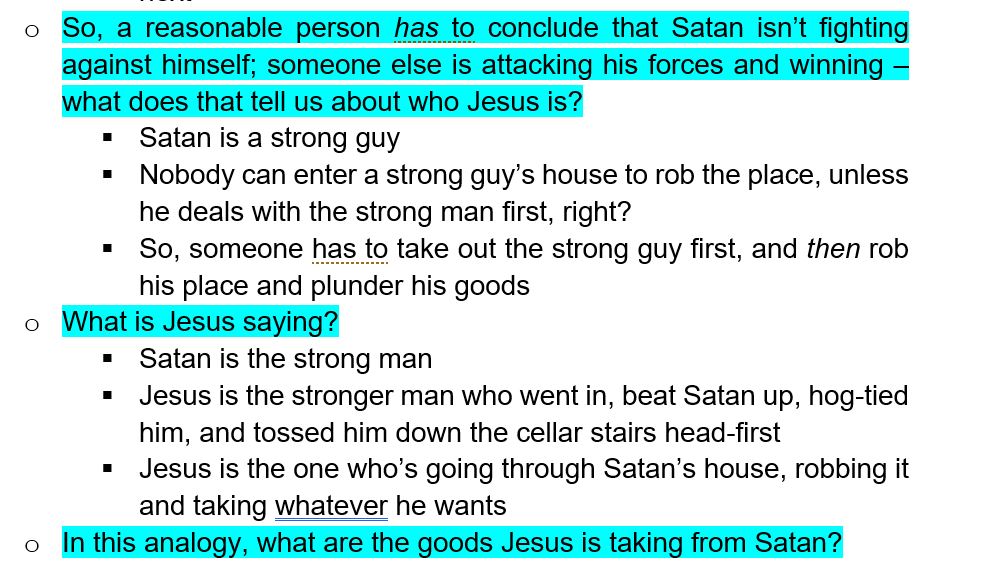

I know this sounds strange, and I’m not sure whether anyone else does it this way. I’d been preaching for years before I took any homiletics classes, so I developed this method on my own. Here is an excerpt from my preaching notes from this coming Sunday, to give you an idea what I’m talking about:

I don’t read this at all; I glance down, remember immediately where I’m going, and just say it. I do the same thing in my secular job as a fraud investigator. I just returned from a subject interview late this evening. Many investigators write out a detailed list of questions before suspect interviews. I don’t, because a real conversation doesn’t go in a neatly structured format. I literally just wrote the four fraud allegations on a piece of paper to orient myself to the topics I needed to cover, and asked all the questions on the fly, keyed to the elements (or “building blocks”) of the various allegations. I didn’t need to have scripted questions because I’d done so much prep work that it all flowed quite naturally. The subject initially denied everything, but I got a full confession in the end! Yay!

So, the bottom line is that there are a million ways to prepare and deliver sermons. Everyone is a bit different.

Tyler is a pastor in Olympia, WA and works in State government.

I learned homiletics long before I studied homiletics. At BJA, I was required to turn in several sermon outlines each week from chapel and church services. I found this so profitable that I did so whenever I heard a sermon, whether or not my classes required it. Over the course of several years, I outlined hundreds of sermons. When I finally took a class in homiletics, I realized that I was already doing most of what was being taught.

G. N. Barkman

Doesn’t seem all that strange to me. One of the major factors in the evolution of my sermon notes system was the fact that I found it very difficult, during actual delivery, to focus on anything written down in front of me. It’s all about talking to the people in the room, and for me that’s where the focus and energy is. So it often felt like bringing everything to a screeching halt if I had to read something other than a Bible passage.

… or so it was for years. So the notes that worked best were extremely concise, and easy to take in visually.

Today, I’m more comfortable reading a bit, but I still don’t look at my notes all that often. They are part plan, part map, and part psychological crutch (In case I get stuck and can’t remember anything… which doesn’t usually happen). For me, if I don’t have the outline and the central “big idea” memorized and front of mind, I’m just not ready to preach. (But yes, in real ministry, you sometimes preach when you are not even close to ready!)

On outlining sermons… yes, huge!

I have to add to Greg’s observation. In high school at Genesee Christian School in Flint, MI, it was decided that all students would take notes of all chapel speakers and all church services we attended and keep them in a notebook and turn them in once a semester to verify we were doing the work.

This put me years ahead in learning to structure sermons… it became very obvious which speakers were preparing well and which were winging it! (Some always winged it). I have been so grateful so many times for that four years of notetaking.

Views expressed are always my own and not my employer's, my church's, my family's, my neighbors', or my pets'. The house plants have authorized me to speak for them, however, and they always agree with me.

I agree with Aaron that, “It’s all about talking to the people in the room, and for me that’s where the focus and energy is.” However, in defense of manuscripting, I believe that the growth of novice preachers should be taken into account.

For the sake of argument, I’m going to assume that “we” all agree that there are advantages to manuscripting a sermon. If there is value to manuscripting, then in my experience, both preaching and observing other novice preachers, with experience the disadvantage of looking down instead of up and at the people in the room goes away.

The first time I ever preached from a manuscript, I was horrified to discover that I looked down far more than I thought I would. Every acting/public speaking instinct in me was screaming at me to look up while I was preaching. But I couldn’t; my eyes were glued to my manuscript. Later, at service review, I mentioned that. My senior pastor smiled and said, “You’ll get better.” By God’s grace, I have gotten better.

I’m not finished growing in this area, but I now look up and make meaningful eye contact the vast majority of the time while preaching. I’ve seen this same growth in other novice preachers.

I’m thankful that the congregation (and my senior pastor) were patient with me and allowed me to make mistakes. I’m a big fan of manuscripting the sermon and have found that some of the method’s weak spots disappear over time and with experience.

Discussion