Deciphering Covenant Theology (Part 21)

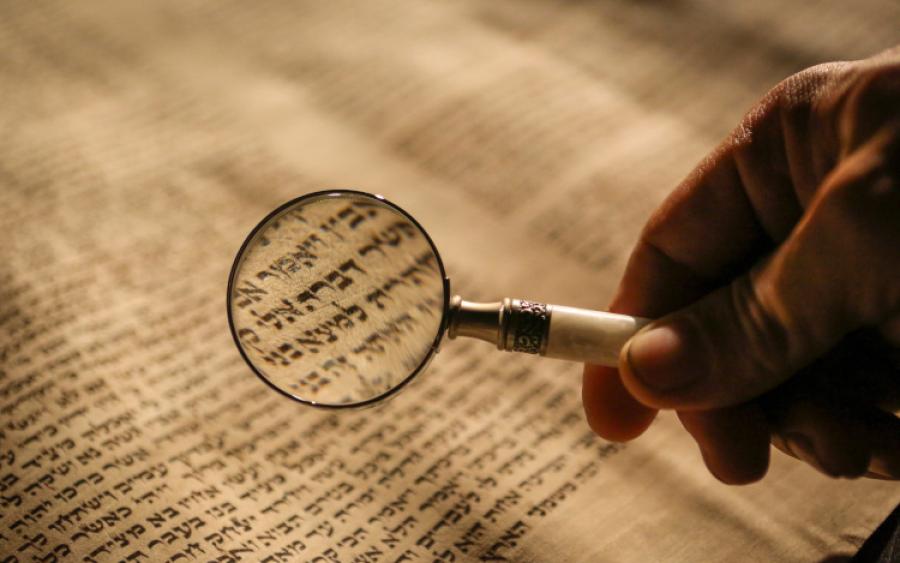

Image

Read the series.

Looking Deeper into the Problems with Covenant Theology

7. By allowing their interpretations of the NT to have veto over the plain sense of the OT this outlook creates massive discontinuities between the wording of the two Testaments. This is all done for the sake of a contrived continuity demanded by the one-people of God concept of the Covenant of Grace.

It has been common for both Covenant Theologians and Dispensationalists to categorize the former as a continuity system and the latter as a discontinuity system. And to some extent this is so. Dispensationalism can be seen as a discontinuity system in the sense that it claims that the Church of the NT is not Israel. CT teaches that the Church and Israel, at least believing Israel, are the same group under the umbrella of the covenant of grace. There is one people of God; ergo, there is continuity in the saints of the two Testaments.

But the objection to CT framed above accuses it as creating “massive discontinuities.” Those discontinuities are hermeneutical in nature before they are anything else. Hence, the much vaunted “continuity” of CT once more comes about as a result of deductions from its own premises. But it does not and cannot come about as a result of believing what the text of Scripture says, particularly in it’s own covenants. I locate the source of this hermeneutical discontinuity in the way CT deals with the NT. At the risk of coming across as dogmatic, I would insist that theological continuity take second place to hermeneutical continuity.

When one takes care to read the Infancy Narratives of the Gospels of Matthew and Luke it ought to be clear that there is a huge emphasis upon the prophetic expectation generated by the Abrahamic and Davidic covenants of the OT (cf. Matt. 1:17). This can easily be seen be a close reading of the angel Gabriel’s words to Mary (Lk. 1:32-33), and to Joseph (Matt. 1:20-23). Then there are the recorded speeches of Mary (Lk. 1:46-55), Zacharias (Lk. 1:67-79), Simeon (Lk. 2:25-35), and Anna (Lk. 2:36-38). Every one of these witnesses displays a covenantal continuity with the OT. Then we get to the Temptation story, and once again we see the covenants taken seriously (Lk. 4:5-7).

I could go on to talk about Matthew 19:28/Lk. 22:30, or Mark 13/Matthew 24. In Acts 1:6 the disciples ask Jesus specifically about restoring the kingdom to Israel. They do this despite having been instructed by the risen Christ specifically about the kingdom (Acts 1:3)! Towards the close of the Book of Acts Paul is still concerned about the “promise [to] our twelve tribes,” which they “hope to attain,” and for which cause he is standing before Agrippa (Acts 26:7). In a word, what we see is interpretive continuity.

Forcing Theological Continuity on to NT Texts

CT, along with NCT cum Progressive Covenantalism and some other approaches, sees a continuum between OT Israel and the NT Church in that the saints in both are seen to be one people under the covenant of grace. Although perhaps overstating it somewhat Merkle observes that, “Covenant theology understands all the biblical covenants as different expressions of the one covenant of grace.” (Benjamin L. Merkle, Discontinuity to Continuity, 15). That being so, there is no room for covenant fulfillment that distinguishes Israel from the Church.

The way this appears in exegesis is that the Infancy Narratives are not taken to be setting up the trajectory of the NT, but at best to be a record of Jewish belief before Christ Himself reinterprets the expectations in His teachings. Taking another example, the statement in Luke 19:11 that the Parable of the Talents was for the explicit reason of disabusing the disciples “because they thought the kingdom of God would appear immediately.” When one adds this teaching to the question about the kingdom being restored to Israel in Acts 1:6 and Jesus’ answer that it was not for the disciples to know the “when” of the kingdom (Acts 1:7), how can one state that,

Acts 1:8 affirms what will be an ongoing and progressive fulfillment of the OT kingdom and Israel’s restoration, which had already begun establishment in Jesus’ earthly ministry. In this light, the apostles’ question in 1:6 may also reveal an incorrect eschatological presupposition. (G. K. Beale, A New Testament Biblical Theology, 139)

But the disciples had just been taught about the kingdom by the King Himself! Are we really to believe they entertained “an eschatological presupposition.”?

Should We Think About Israel and the Church in Terms of Discontinuity?

I also think it is wrong to talk about the discontinuity between Israel and the Church until we have appreciated the roles that both have within the wider covenantal program of God. Both “peoples” have a place within the Abrahamic covenant: Israel in terms of natural descendants and land, the Church in terms of the blessing upon the nations both through Abraham’s Seed Jesus Christ and our faith-participation in Him (Gal. 3:16-29). And if we are paying attention we can see that both the Church right now and the remnant of Israel in the future are parties to the New covenant in Christ (cf. 1 Cor. 11:25; Rom. 11:25-29).

Furthermore, we must not forget that both entities play an implicit and strategic part in the Creation Project itself as it unfurls in history. It is therefore a mistake to refer to the Church as a “parenthesis” because those leave the impression that a new thought has been interjected into a sentence which could stand alone without it.

It is better to think of God’s Creation Project as containing several strands or programs which go into operation at different times in the history of the fallen world. The plan for Israel begins after the confusion of languages and separation of nations (Gen. 10 – 11). The plan for the Church begins after Israel’s rejection of Jesus’ ministry (Acts 2). Since God has unfinished business with Israel the plan to save the nation is taken up after the Church is complete (Rom. 11:25-29). I believe that it is better to think in terms of these programs within the one Project that God has for Creation. The Church is not in any sense “Plan B,” it is Plan 1b. There’s a big difference!

Paul Henebury Bio

Paul Martin Henebury is a native of Manchester, England and a graduate of London Theological Seminary and Tyndale Theological Seminary (MDiv, PhD). He has been a Church-planter, pastor and a professor of Systematic Theology and Apologetics. He was also editor of the Conservative Theological Journal (later Journal of Dispensational Theology). He is now the President of Telos School of Theology.

- 34 views

Discussion