Who Is Melchizedek?

Body

“Melchizedek, the king-priest of Salem, is foundational for understanding how Jesus occupies the offices of king and priest—a dual honor that finds little to no precedent among Israelite kings.” - TGC

As iron sharpens iron,

one person sharpens another. (Proverbs 27:17)

“Melchizedek, the king-priest of Salem, is foundational for understanding how Jesus occupies the offices of king and priest—a dual honor that finds little to no precedent among Israelite kings.” - TGC

Read Part 1.

There are different approaches to the subject of midrash (or its plural, midrashim). Put simply, a midrash is a Jewish style of elaboration, exposition, or “mining” of a text. The idea is to find both obvious teachings and teachings not immediately obvious—but still latent within the text. In my view, when a New Testament author “unlocks” teachings not immediately obvious, he has uncovered a “mystery.” Jesus did this to prove the resurrection from the Torah, much to consternation of Sadducees (Matthew 22:29-32).

The Book of Hebrews is one midrash after another. For example, chapter 6 is a midrash of Numbers 13-14. Chapter 7 is a midrash on Genesis 14:17-20 and Psalm 110:4, and it highlights the “loud silence” in these Old Testament texts.

To our thinking, midrash can sometimes be a bit of a textual stretch. That is why we trust the New Testament writers: they were supernaturally inspired of God. On the other side of the coin, we should demonstrate hesitation toward non-canonical midrash.

The writer to the Hebrews (perhaps Apollos?) is trying to convince tottering Jewish believers to remain true to Jesus Christ. He is also trying to comfort these believers who are shaken up because some of their peers had turned away from faith in Jesus Christ and returned to non-Messianic Judaism.

The writer is out to prove that faith in Jesus is better than Judaism without Jesus by proving that Jesus is Superior to anything Judaism has to offer. Prior to chapter 7, he has proved Jesus’ superiority by asserting His deity. Now he is proving Jesus’ superiority in His humanity. The Melchizedek argument demonstrates that Jesus (in His humanity) is superior to Abraham, the man considered the Father of the Jewish faith.

Jewish imagination did a lot with Melchizedek, and during the medieval times, they viewed him as none other than Noah’s son, Shem. The Jewish Encyclopedia gives many examples of Jewish creativity:

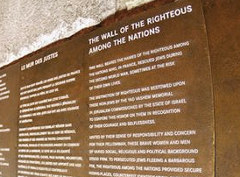

Yad Vashem Holocaust Memorial in Jerusalem not only remembers those who died in Europe during that awful period from 1933-45, it also honors non-Jews who protected and rescued their Jewish neighbors from death. They are memorialized on the Avenue of the Righteous Gentiles.

In Exodus 17 and 18 I have pondered how the Amalekites, history’s “first terrorists” (17), contrasted so sharply with the Midianites (18) in the ways the two “Gentile” peoples related to Israel after they departed from Egypt. The Amalekites were descendants of Abraham through Esau who viciously attacked Israel (Exo.17:8-16) by killing the stragglers at the rear of the Israelite column (Deut. 25:17-19). In both of these passages God promised eternal vengeance on this people who never ceased in their hatred for Israel until they were finally eliminated in the days of Esther and Mordecai (Esther 3:1; 7:10; 9:14).

The Midianites, however, were descendants of Abraham through Keturah who greeted peacefully the Israelites in the person of their priest, Jethro (Exo. 18:1-12). The father-in-law of Moses is one paradigm of the righteous Gentile who provides for Israel rather than attacks them. While Jethro is best known for his sage counsel to Moses to recruit a team who could help him in his excessive labors (Exo. 18:13-27), there are also some interesting parallels with an earlier righteous Gentile named Melchizedek. Note some of these amazing points of comparison between the two, first suggested to me by John Sailhamer.

The writer to the Hebrews was distressed by the spiritual immaturity of his readers. He wanted to discuss theology with them—specifically, the calling of Christ as a high priest after the order of Melchizedek (Heb. 5:10-14). He made it clear that the Hebrews had been saved long enough (“when for the time”) that they ought to have mastered this topic (“ye ought to be teachers”). Instead, he had to rehearse certain elementary teachings of biblical doctrine (“the first principles of the oracles of God”).

The writer’s disappointment with the immaturity of the Hebrew believers was what fueled the warning passage of chapter 6. Not until chapter 7 did he return to the theme that Christ is a high priest after the order of Melchizedek. When he finally got back to it, however, he penned one of the most difficult and detailed arguments in all of Scripture. This argument is highly instructive concerning the nature of Christ’s high priesthood.

Nothing in Hebrews 7 is really new. Everything in the chapter is inferred from three sources. The first source is the Genesis account of Melchizedek, a three-verse snippet of narrative (Gen. 14:18-20). The second source is a single verse (Ps. 110:4) from a Messianic psalm. The third source is a general knowledge of the history and culture of Israel. From these short sources, the writer constructs an elaborate discussion of the high priesthood of Christ after the order of Melchizedek. So detailed is the discussion that only the outlines can be explored here.

Discussion