Tradition Suspicion

Rightly viewing tradition

The religious scene of South Africa is populated by mainline Protestant churches, some of whom place great emphasis on tradition. However, in many of these churches, the gospel itself is all but invisible, an assumed but unseen foundation of the house. The problem is, most of those in the house have never clearly heard or understood the gospel, and the same might be said for many of the religious professionals who teach there.

Once a person comes under the sound of the true gospel and believes it, he is struck by the sad irony of having attended a church for decades in which the gospel itself was never proclaimed. Inevitably, this new-found knowledge of biblical truth tends to produce a desire to distance himself from anything and everything connected with the former church, including any allegiance to tradition. Since such churches often rely on and turn to their traditions, the new Christian concludes that tradition must be part of the problem that caused the gospel itself to go into eclipse in such churches.

The truth is, tradition is indeed a double-edged sword. When tradition preserves the truth, it is a reliable record that comes to a newer generation without that generation having to re-invent the wheel. When tradition preserves untruths, it becomes the guardian of a lie that will not die. It is an accomplice to deception, using its antiquity to give credibility to its spurious beliefs and practices.

In reaction to gospel-eviscerated traditionalism, it is possible to identify tradition itself as the problem. This would be a mistake. If a particular museum keeps something worthless, this does not negate the value of museums. Clearly, what matters is what tradition preserves. A gospel-eviscerated tradition is a bad one. A gospel-centered tradition is a good one.

Republished with permission from

Republished with permission from  Reprinted with permission from

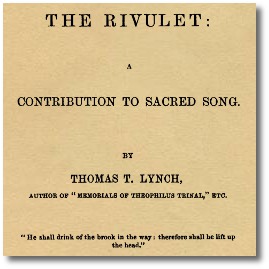

Reprinted with permission from  “Dr. Watts’s Hymn-book does not satisfy and suffice me,” said London Congregational minister Thomas Toke Lynch to his Mortimer Street church in 1851 (

“Dr. Watts’s Hymn-book does not satisfy and suffice me,” said London Congregational minister Thomas Toke Lynch to his Mortimer Street church in 1851 (

Also in this series:

Also in this series:

Discussion