Toward Expository Preaching

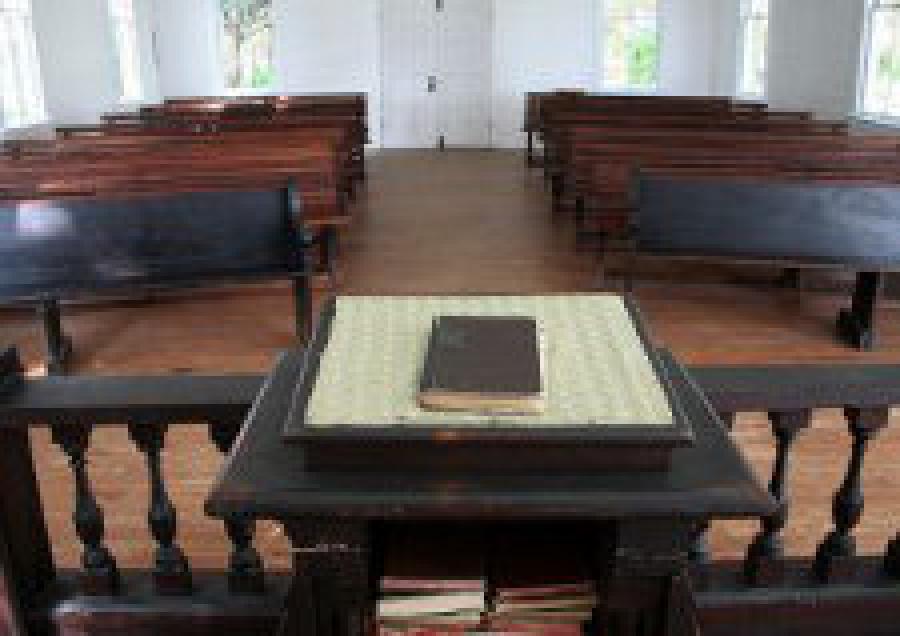

Image

From Faith Pulpit, Winter 2014. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

God’s people understand that the Bible demands the preaching of God’s Word. Faithful ministers will, therefore, preach God’s Word, and God’s people will listen to the proclamation of His Word. Passages such as 1 Corinthians 1 and 2 and 2 Timothy 3:15—4:2 demonstrate the priority God places on preaching the Word. Paul insisted that God’s methodology is the “foolishness of the message preached” (1 Cor. 1:21). The preacher must proclaim the Word “not with persuasive words of human wisdom, but in demonstration of the Spirit and of power” (1 Cor. 2:4). He further instructed Timothy to “preach the word” (2 Tim. 4:2).

The Background of Preaching

The ancient world recognized the value of spoken words. Aristotle’s On Rhetoric provides insight into the importance of public speaking. He defined speaking in terms of the ethos (character) of the author, the pathos (emotion) of the author, and the logos (content) of the message. Aristotle argued against the manipulation of an audience and concluded that the character of the author must come before either emotion or the content. All of these elements find emphasis in a class on preaching.

Classic education also emphasized the value of spoken words. Classic education typically divided itself into three categories (trivium): grammar, logic, and rhetoric. This form of education is actually finding a rebirth in some school curricula. The New Testament church found itself in the cultural backdrop of these educational emphases in the first century.

New Testament Meaning

While the presence of a secular influence on public speaking during the church’s formative years cannot be denied, the New Testament emphasis upon preaching raises the expectation for the public communication of the gospel. The content of preaching is the written Word of God, and the messenger stands on the authority of God as its author. This truth demonstrates itself in the two primary terms for preaching found in the New Testament. The first term, euangelidzo, relates to “gospel” or “good news” and emphasizes the content of preaching. Preaching communicates the content of the gospel. The second term, karusso, means to “proclaim as a herald” and thus emphasizes the manner in which the message is delivered. The message must be proclaimed with authority as one representing the King.

If a sermon is not an exposition of Scripture, then it is only a sermon about the Bible. Too many sermons today find their content filled with neglect (or even errors) of exegesis, interpretation, and theology in a given passage. Such sermons fail the basic test of exposition. They may be sermons about the Bible but are little more than the preacher’s opinion without the foundation of the Bible behind what he is saying.

Expository Preaching

Expository preaching, by definition, consists of the foundational elements of exposition, which are exegesis, hermeneutics, and theology(both Biblical and systematic). First, exegesis forms the basis for all faithful Bible study. For this reason training for preaching emphasizes such things as the Biblical languages, diagramming, word studies, and cultural backgrounds. Second, hermeneutics done properly will always depend on a grammatical, historical, contextual meaning of a passage. A Bible passage has only one meaning and that meaning is the one intended by the original writer of the Scripture. The context always takes precedence in what a passage means. Third, theology means that the interpretation of a passage fits with the rest of Scripture. The meaning of any text will fit with other passages in what becomes theology. This is what “no prophecy of Scripture is of any private interpretation” means in 2 Peter 1:20. Expository preaching must first and foremost be exegetical in that it accurately contains the right exegesis, interpretation, and theology.

Defining expository preaching can be as difficult as trying to nail Jell-O to the wall. If you survey twenty authors of preaching books, you will get twenty definitions. One well-known author states that you can’t define expository preaching and then proceeds to define it.1 Most definitions have many similar threads and many differences that come down to whether you look at the forest, leaving out some details, or look at the trees, giving an abundance of details. My definition is the following: “Expository preaching is the communication of divine truth through human personality with a view to persuasion.” This definition prefers to see more forest than individual trees. First, the definition emphasizes the subject matter, namely, divine truth rather than human wisdom of any sort (1 Cor. 2:1–5).

A second emphasis is the manner of communication, which is through a man. This means that each individual will process the passage and deliver it with some distinctiveness. An individual’s personality plays a critical role in formulating the preaching event.

A third emphasis is the purpose for preaching, which must include persuasion. Expository preaching not only targets the mind but also the heart. “A sermon is not an exercise in exegesis, but a declaration of truth to move us to moral action. It is truth mediated through a man.”2

Expository preaching contains many aspects that demonstrate it is both a science to be studied and an art to be developed. The following suggestions should be helpful for both the novice and the experienced preacher.

Preach the Word

We preachers should be sure to preach the inerrant Word of God. The very fact that we have truth should demand of us a steadfast commitment to preaching the Word. Robinson made a strange statement when he wrote, “an orthodox doctrine of inspiration… sometimes gets in the way of expository preaching.”3 This should never be our approach. Inspiration makes the case for authority in the pulpit. The preacher proclaims the sacred text, the very words of God for humanity. An inerrant Bible frees the preacher to preach the words of God.

Foundational to understanding the inerrant Word is the fact of the Bible’s relevance to today’s world. The Bible is timeless in its application to life. The preacher must recognize both the unchanging nature of the Word and the application of the Word to life’s everyday issues.

Preach Exegetically

The preacher needs to do his homework and know what the Scriptures say. We must

- follow the thought and intent of the Bible writer;

- keep ourselves grounded in the context of the passage without fanciful flights into rabbit trails foreign to the passage;

- follow the structure of the passage for certainly every passage has a structure of some sort; and

- never impose our ideas over the ideas that the text brings forward. Our thoughts might be good thoughts and even Biblical thoughts, but if they are not in the text before us, then we have stopped preaching the Bible and started preaching about the Bible.

A word of caution is needed here. The message must be exegetically prepared and exegetically driven, but we should not bring exegetical handiwork to the pulpit. We do not need to spout Greek terms, Hebrew constructions, or technical jargon to our church people. There are times when a technical issue makes a difference in interpretation and thus needs to be part of the sermon, but generally those instances should be few and far between. As well, sermons are not the place to give all the wrong ways theologians interpret a passage. A sermon is something akin to an iceberg where 90% of the labor-intensive research stays hidden below the surface. Our people understand that the sermon they see above the water line is supported by a depth of time and commitment to the exegetical resources of our study.

Preach with a Theme

Every passage of Scripture was written with a purpose. The preacher should never preach unless he is prepared to identify the passage’s purpose. Why did the Biblical writer pen these words? Until the preacher can answer that question, he does not understand the passage. Further, the purpose of the sermon should mirror the purpose of the text. Whether one calls this concept the “big idea,” the “theme,” or the “proposition,” the sermon’s purpose should flow directly from the purpose of the Biblical writer in the text. J.H. Jowett stated that, “no sermon is ready for preaching…until we can express its theme in a short, pregnant sentence as clear as crystal. I find the getting of that sentence is the hardest, the most exacting, and the most fruitful labour in my study.”4

We should identify the passage’s main point and develop it into a concept that intersects life today. If we sharpen the concept into an understandable sentence, we have a theme that will tie the sermon into a cohesive unit. The theme serves several important sermonic functions. First, each of the main points of the passage will be a development of this theme, providing both support and argument. Second, this well-crafted theme should fit virtually anywhere in the sermon. Finally, the theme provides the basis for both the conclusion and the final persuasion of the sermon.

Preach the Gospel

Preachers ought to preach the gospel regularly. We should emphasize in the pulpit the great truths of sin, the cross, the blood of Jesus, redemption, and forgiveness. Paul instructed Timothy to “do the work of an evangelist” (2 Tim. 4:5). Every sermon need not be evangelistic in its entirety but certainly some should. A preacher who possesses a compassion for the lost will demonstrate that emotion through his preaching. Certainly most, if not every, passage will touch upon the gospel at some point. We must connect our sermons to the gospel. This might mean connecting the passage to some of the great overarching themes of the Bible such as sin, redemption, or judgment. Few students understand how to preach evangelistically because they so rarely see it modeled in their churches. Emphasize the precious blood of Christ and lift high the cross on which He died. Preaching this way will give our people confidence that if a visitor comes with them to a service, the gospel will be proclaimed from the pulpit.

Preach with Variety

Preaching books and homiletic teachers have long made a distinction between expository preaching, textual preaching, and topical preaching. The distinction between the expository and textual sermon typically is defined as the length of passage. Further, topical preaching as commonly practiced has little to do with exegesis, context, or authorial intent but often uses the text only as a springboard to go any direction the preacher has in mind. This sermon is not an exposition of the Bible even if the sermon’s content might be Biblical. Rather, this is preaching about the Bible.

I define expository preaching not in terms of the length of the passage but rather in the attitude that the preacher brings to the text. We must always preach Scripture exegetically, understanding both the Biblical writer’s intent and the context in which the passage is found. Anything less falls short of expository preaching. Too much is made of the length of a passage that meets these criteria. An expository sermon may be based upon a chapter(s), a paragraph, a few verses, a single verse, or even a phrase. It may be biographical, doctrinal, or topical as long as the preacher always follows the writer’s original intent and adheres to the context. The important point is the attitude the expositor brings to the text. We ought to develop patterns of variety within the model of expository preaching. Certainly we may balance a regular pattern of book studies with other legitimate types of expository sermons. We should preach using a variety of expository styles that will keep us engaged and our congregation anticipating what is coming.

Preach with Passion

Christ preached with authority (Matt. 7:29). We should share this conviction of the truth of Scripture, and this conviction should then translate into passion. Too many preachers lack the fire the pulpit requires. Preaching is not designed to accomplish an academic exercise. Should a sermon be just a lesson to learn or an obligation to discharge? A passage that works its way through our life will translate itself to the pulpit in terms of passion. While our personality plays a significant part in how we communicate our passion through preaching, we ought to generate intensity, zeal, enthusiasm, urgency, and energy in communicating a truth that has changed our life.

Our compassion for God, His Word, and people ought to overflow into zeal in preaching. Robert Delnay wrote, “To the preacher who loves the Bible, will he not feel emotional about it? And will not that emotion often overflow in passion for given verses and doctrine?”5 As one teacher has said, “Light a fire in the pulpit and people will come to watch it burn.”

“Preach the word! Be ready in season and out of season. Convince, rebuke, exhort, with all longsuffering and teaching” (2 Tim. 4:2).

Notes

1 Haddon W. Robinson, Biblical Preaching: The Development and Delivery of Expository Messages, 2nd ed. (Grand Rapids: Baker Academics, 2001), 21.

2 Alex Montoya, Preaching with Passion (Grand Rapids: Kregel Academic & Professional, 2007), 45–46.

3 Robinson, 23.

4 J. H. Jowett, The Preacher: His Life and Work (Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 1968), 133.

5 Robert G. Delnay, Fire in Your Pulpit (Schaumburg, IL: Regular Baptist Press, 1990), 101.

Daniel Brown Bio

Daniel Brown serves on the faculty of Faith Baptist Bible College and Seminary where he provides instruction in pastoral ministry and Bible. He has served in a variety of pastoral roles in addition to teaching on the faculty at Denver Baptist Bible College and Central Baptist Theological Seminary. Dr. Brown holds the MDiv and ThM from Detroit Baptist Theological Seminary and the DMin from Westminster Theological Seminary. He and his wife, Mary Jo, have been blessed with four daughters.

- 5 views

Discussion