The Guy Who Taught Us Not to Interpret the Bible Literally

College freshmen are impressionable people. Once as a college freshman I heard a pastor who was pretty good with his Greek New Testament explain how Jesus encountered demons. The pastor interpreted the phenomenon literally. I was impressed, so I bounced my new-found knowledge off my dad.

Wrong forum! Dad was a doctor. He let me know in no uncertain terms, that whatever Jesus did, He did not heal diseases by eliminating evil spirits. That was thinking for the “quacks” and the “kooks.” As we talked, our distinct belief systems had a major collision. I backed off, but for the next several months, whenever the subject came up, my father took pains to instruct the family, so that we all stayed scientifically orthodox.

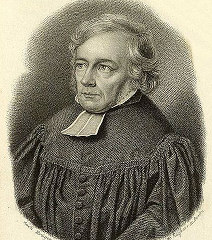

That conflict demonstrates the essential difference between conservative and liberal theology. True Liberal theology began with the German scholar, Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768-1834; the term used in Germany is “Historical-critical Theology”). Schleiermacher had a great desire to defend the Christian faith and an intense interest in Bible study. He was also fascinated with European philosophy and drank deeply from the well of German idealism.

Stellar intellect that Schleiermacher was, he spent most of his student discussions talking about the Christian faith with his unbelieving intellectual friends. His first book was, On Religion: Speeches to its Cultured Despisers. Grenz and Olson say, “None strove so valiantly to reconstruct Christian belief to make it compatible with the spirit of his age.”1

His journey and influence

Schleiermacher was more than a theologian; he was also one of Europe’s leading thinkers in the philosophy of education. In Berlin he was seen as a kind of Dr. Spock, to whom nearly everyone of the intellectual class came for advice on child rearing. Schleiermacher was also an effective communicator. At the height of his ministry he always preached to capacity crowds. Even Charles Hodge, who listened to Schleiermacher preach in Berlin, pronounced him an evangelical (Charles, did you really mean that?).

One of the articles of faith of European philosophy in the late 1700s was the impossibility of miracles in nature. Descartes, Spinoza, Leibnitz and Hume, all brilliant writers, had argued convincingly that the laws of nature are so established as to make miracles impossible, even for God. These four, together with other philosophers, established the most pervasive paradigm of modern western thinking: “No Miracles.”

By the time Friedrich Schleiermacher became a university professor, the debate about miracles was over. He had to find a way to make Christianity convincing without the supernatural. This was a mega-shift in Christian theology, which had always accepted the supernatural (e.g., the writings of the Apostle Paul). Schleiermacher grafted the paradigm of European philosophy into Christian theology. Faith, he argued, is based on religious feeling. Science is based on fact. Man needs both. Science writers Nancy Pearcey and Charles Thaxton write aptly, “Liberal theology, arising in the nineteenth century, was essentially an adaptation laid down by classical determinism, that nothing can intervene in nature’s fixed order.”2

Accordingly Schleiermacher could not take the Bible, with its many accounts of the supernatural, at face value. He could not give it a literal interpretation. After all, it had been composed by people with more primitive thinking than our own.

He could not elevate the Bible above human experience—even in its statements about God. He could not use the Bible to comment on history, since, “religion waves all claims to anything belonging to the two domains of science and morality.”3 No doubt you have heard Schleiermacher paraphrased like this: “The Bible is not a textbook on science, so let’s leave the Bible out of the discussion when we talk about how life originated.”

Out with the Devil

Schleiermacher deserves credit for being consistent. Since ruling out the supernatural requires one to rule out the devil as well, he did. But as a critical thinker, Schlieiermacher still had to deal with what the New Testament says about the devil. In his The Christian Faith, he handles over 20 instances of New Testament discussions of the devil and demons.4 Per Schleiermacer, the devil spoken about by Jesus in the parable of the wheat and the tares is not a real devil. Jesus really meant that slanderous brethren sow the tares. For each passage Schleiermacher gives a different interpretation of “devil.”

Think of it: there are twenty interpretations in all. His hermeneutic is ingenious, to be sure. The Greek word diabolos does have more than one sense in Greek lexicons. Schleiermacher used this fact to his advantage, and then some. He was consistent in this theology, but pity the poor Bible reader who has never hear a liberal theology lecture and has no knowledge of the 20 ways to interpret “devil.” He probably believes there is just one real one.

If Schleiermacher is right, a reader must understand Liberal theology before reading the Bible. So 95 percent of Christians might as well put down their Bibles, since they will never correctly understand them—and that has been the effect of Liberal teaching. Sixty-two percent of the German public never picks up a Bible to read it—not even once a year. In the early days of the American republic, the average man—believing the Bible offered the most important knowledge available—would return home from church every Sunday and read his Bible.5 In the wake of Liberal theology, this practice is no longer current in America.

Enduring influence

When I was a young Christian, the favorite whipping-boy for conservative pastors was the Liberal pastor, Harry Emerson Fosdick. But as Fosdick’s influence has faded from Christianity, Schleiermacher’s has remained enormous. Outside the halls of theology few know much about Schleiermacher. But among students of theology his thinking continues to stimulate study. New books about his ideas are written every year.

Fifty years ahead of The Origin of the Species, Dr. Schleiermacher was the Charles Darwin of Christian theology. His ideas did more than those of any other theologian to pave the way for the acceptance of theistic evolution. That is why whenever there is a public debate about some biblical subject in the western world, the media can always find a theologian to interpret the Bible non-literally and according to prevailing political or cultural thinking. This is the hermeneutic of human experience, the hermeneutic that divides liberal theologians and pastors from conservative ones. Those who do interpret the Bible literally are promptly labeled “fundamentalists” by Liberal theologians or by a press sympathetic to Liberal ideas. In their view, the thinking of Bible literalists, no matter how fact-based, is one or two centuries behind the times.

By allowing European philosophy to determine the parameters of Bible interpretation, Friedrich Schleiermacher made a serious mistake. Philosophies come and go like sand dunes. Instead, he should have heeded the Apostle Paul: “For since, in the wisdom of God, the world through wisdom did not know God, it pleased God through the foolishness of the message preached to save those who believe” (1 Cor. 1:21). Paul kept pace with the skeptical philosophers of his day. His use of the literal hermeneutic and his undying belief in the God of the supernatural eventually dominated western thought (at least until the time of Schleiermacher). The gospel spread, and continues to spread despite human philosophy.

We cannot know God by beginning with man. God must reveal Himself to us. According to Isaiah 55:7-11, God’s thoughts surpass our thoughts; God’s ways surpass our ways. All our intellect cannot match His thinking, plans, or actions in the world. Either we believe that much of the substance of our faith comes by pure revelation from God, or we effectively tell God that He may not talk to us about anything we cannot find out on our own—at least not anything going on in this world. Schleiermacher was a fascinating thinker, but his theology does not know the true and living God, the Father of our Lord Jesus Christ.

Theologians who believe in the supernatural, and a literal hermeneutic, have striven valiantly—and often successfully—in the last 200 years to keep the faithful trusting in the God of the Bible. But in recent times the group taking the battle back into the realms of the anti-supernaturalists has not been the theologians. It has been natural scientists of the creationist movement. This movement began with a commitment to Bible literalism and then viewed scientific discovery from a new perspective. We wish it the best of success.

And my dad? After enough Bible reading and enough listening to Bible exposition, he became a Bible literalist. He passed from this life at age 90. Medicine and Science remained his passion until his dying day, but to him, the Bible topped everything he discovered. He was one more proof that human beings can believe the Bible and think scientifically at the same time, without splitting the two into separate realms. Schleiermacher’s division is wholly unnecessary. We should simply accept the Bible as it’s written. What it says is more brilliant than any ideas this world has to offer.

Notes

1 Stanley Grenz and Roger E. Olson, 20th Century Theology (Downer’s Grove: InterVarsity, 1992), 40.

2 Nancy R. Pearcey and Charles B. Thaxton, The Soul of Science (Wheaton: Crossway, 1994), 215.

3 Friedrich Schleiermacher, On Religion: Speeches to its Cultured Despisers, Trans. John Oman (New York: Harper & Row, 1958), 77.

4 Friedrich Schleiermacher, The Christian Faith, H.R. Mackintosh and J.S. Stewart, Eds. (Edinburgh: T & T. Clark, 1928), 164-166.

5 Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, 13th ed. J.P. Mayer, Ed. (New York: Harper and Row, 1969), 542.

Marsilius Bio

“Marsilius” has a PhD in systematic theology and many years of pastoral ministry experience. He has a temporary need to remain anonymous.

- 10 views

Discussion