Dispensationalism 101: Part 1 - The Difference Between Dispensational & Covenantal Theology

Image

From Dispensational Publishing House; used with permission.

What is the difference between dispensational and covenantal theology? Furthermore, is the difference really that important? After all, there are believers on both sides of the discussion. Before entering into the conversation, there are a couple of understandings that need to be embraced.

Tension & Mystery

First and foremost, there is the need to recognize the tension—and mystery—which has characterized this and other theological discussions for centuries. There will probably never be a satisfactory answer or clarifying article that will settle the debate once and for all for both parties. There will be no end to the discussion until Jesus Christ returns (either in the rapture of His church or earthly millennial reign, in my estimation).

Man is limited in his ability to understand and articulate each nuance of theology. Not everything can be comprehended about God and His sovereign purposes. Scripture reminds repeatedly of the humbling fact that God is majestic, infinite and incomprehensible. His ways are inscrutable—He does not have to explain Himself. Passages such as Job 11:7 (NASB) ask great questions such as,

Can you discover the depths of God?

Can you discover the limits of the Almighty?

The Psalmist reminds us, “Your thoughts are very deep” (Ps. 92:5) and we “cannot attain” them (Ps. 139:6). Recall, as well, Isaiah’s record, that:

“My thoughts are not your thoughts,

Nor are your ways My ways,” declares the LORD. (Isa. 55:8)

Though there are scores of passages, one more is Paul’s doxology in Romans 11:33-34 in which he proclaims “the depth of” God’s “wisdom and knowledge,” with none to counsel Him. God transcends human comprehension, extends beyond human logic, and remains above man’s ability to reason and deduce. John Wesley was reported to have said, “Give me a worm that can understand a man, and I will give you a man who can understand God.”1 Surely “His greatness is unsearchable” (Ps. 145:3).

Bible-based, Christ-centered & God-honoring

Second, and equally important, is the need during this exchange to be Bible-based, Christ-centered and God-honoring. Though we are entitled to our own opinion, we are not entitled to our own truth. When speaking, the only basis for authority is the inspired, inerrant, authoritative and sufficient Word of God. The truth of the Bible is objective, propositional reality that is to be unpacked through cautious and diligent exegesis rather than hearsay and speculation.

Notice the third caveat here—God-honoring. When dialoging with fellow believers on opposing issues, we must be sober-minded and gracious. We cannot win the opposing side if we are being pejorative and unkind. We have no entitlement for condescending comments or judgmental jabs. We want to develop a winsome case, rather than use mockery or suggestions that the differing side is engaging in heresy on this matter. Many times in the readings of Christian academic papers there can be much unchristian cajoling that does not honor Christ. Let us honor fellow servants of Christ rather than do what one well-known evangelical did while at a rival school on this issue, when he called their view goofy. We must practice Christian charity as we honor one another in Christ.

The intent of this series of articles is not to fully flesh out the views of either dispensational or covenant theology, but to show the clear distinctions between them and why—Biblically—dispensational theology is to be preferred.

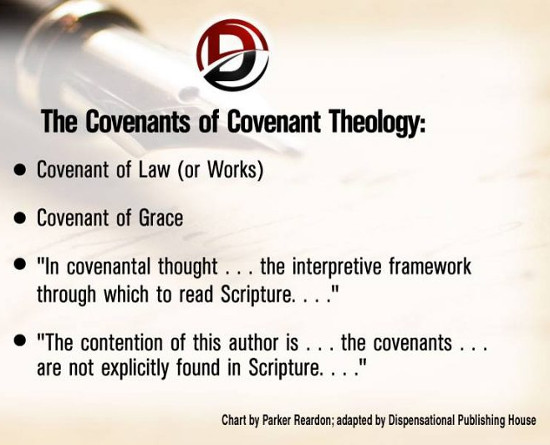

Covenantalism in a Nutshell

The terms covenantal and Reformed are often used interchangeably. There are dispensationalists who speak of being Reformed, yet the way they use the term Reformed is in respect to salvation, referring to the doctrines of grace. Another might refer to himself as a Calvinist-dispensationalist, but this is a rather awkward phrase, since Calvinism is typically used in the discipline of soteriology, not eschatology. This designation would be used to refer to men like John MacArthur and faculty from his school, The Master’s University,2 and others who have embraced the doctrines of grace and who apply a consistently literal hermeneutic, especially in the prophets, while not reading Jesus into every Old Testament verse or giving the New Testament priority.3

When trying to define a system and associate certain teachers with it, there are nuances that make such a feat difficult. For example, James Montgomery Boice was pretribulational4 and premillennial,5 yet he also practiced paedobaptism.6 Not all covenantalists are amillennial7 or postmillennial. And not all premillennialists are dispensationalists (e.g., Boice and George Eldon Ladd).

We will begin next time by thinking about the covenants in covenantal thought, using the chart below to illustrate the concepts that are involved.

Copyright © 2017 Dispensational Publishing House, Inc., used with permission.

Notes

1 Our Daily Bread, Sept.-Nov. 1997, page for Nov 6.

2 John F. MacArthur, Faith Works (Dallas: Word Publishing, 1993), p. 225.

3 More of these particulars will be augmented later in the series.

4 Pretribulationism teaches that God will remove His church from the Earth (John 14:1-3; 1 Thess. 4:13-18) before pouring out His righteous wrath on the unbelieving world during seven years of tribulation (Jer. 30:7; Dan. 9:27; 12:1; 2 Thess. 2:7-12; Rev. 16).

5 Premillenialism teaches that Jesus Christ will return to earth and rule with His saints for a thousand years. This is a time where He lifts the curse He placed on the earth and fulfills the promises given to Israel (Isa. 65:17-25; Ezek. 37:21-28; Zech. 8:1-17), including a restoration to the land they forfeited through disobedience (Deut. 28:15-68).

6 Paedobaptism is the practice of baptizing infants or children who are deemed not old enough to verbalize faith in Christ.

7 Amillennialism is the belief that the thousand years referenced by John in Revelation 20 are not a literal, specific time.

Parker Reardon Bio

Parker Reardon is a graduate of Word of Life Bible Institute, Pensacola Christian College and The Master’s Seminary, where he received a doctorate in expository preaching. He is currently serving as the main teaching elder/pastor at Applegate Community Church in Grants Pass, OR, and as adjunct professor of theology for Liberty University and adjunct professor of Bible and theology for Pacific Bible College.

- 259 views

….the author’s humility and note that if we win by foul play, we lose. That said, perhaps a quick description of covenant theology from a covenant theology source would be a nice bit of “good faith” in the follow-on. It is interesting as well that we might say that covenant theology might be described as dispensationalism with only two dispensations instead of…was it 7? (count me as “learning” here!)

A final note is that we ought to be careful about the language and the terms selected, as I believe dispensationalism derives from the KJV term “dispensation” for economy that does not show up in many modern translations, and I’d guess there are multiple translations for Strong’s 1285 as well.

Aspiring to be a stick in the mud.

The recognition of dispensations in Scripture is not a distinguishing factor between Covenant Theology and Dispensationalism. As the Westminster Confession of Faith stated in 1646, “There are not therefore two covenants of grace, differing in substance, but one and the same, under various dispensations.” (WCF 7.6)(boldface added). ” Charles Ryrie recognized this:

What marks off a man as a dispensationalist? What is the sine qua non of the system? ….

Theoretically the sine qua non ought to lie in the recognition of the fact that God has distinguishably different economies in governing the affairs of the world. Covenant theologians hold that there are various dispensations (and even use the word!) within the outworking of the covenant of grace. Hodge, for instance, believed that there are four dispensations after the Fall—Adam to Abraham, Abraham to Moses, Moses to Christ, and Christ to the end. Louis Berkhof writes … of only two basic dispensations—the Old and the New, but within the Old he see four periods and all of these are revelations of the covenant of grace. In other words, a man can believe in dispensations, and even see them in relation to progressive revelation, without being a dispensationalist.

Dispensationalism Today (Moody Press: Chicago 1965), 43-44. This does not make Covenant Theologians Dispensationalists.

Likewise, Dispensationalists recognize the various Covenants in Scripture and, to a greater or lesser degree, their importance. I appreciate Dr. Henebury’s continuing efforts to persuade Dispensationalists to embrace the importance of the Biblical Covenants. This recognition of the Biblical Covenants, however, does not make Dispensationalists Covenant Theologians.

Dr. Reardon signals his grounds for distinction in the following phrase: Dispensationalists are those “who apply a consistently literal hermeneutic, especially in the prophets, while not reading Jesus into every Old Testament verse or giving the New Testament priority.” He implies that Covenant Theologians do the reverse. In response, Covenant Theologians will deny that they inconsistently apply a literal hermeneutic, even in the prophets. Rather, they will say that Dispensationalists use a woodenly literal hermeneutic that does injustice to the plain reading of Scripture in grammatical-historical context. They will concede that “beginning with Moses and all the Prophets, [Jesus has] interpreted to them in all the Scriptures the things concerning himself,” but this is merely what Luke 24:27 plainly and literally says. Finally, Covenant Theologians will state that “The Word of God, which is contained in the Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments, is the only rule to direct us …” (WSC 2)(boldface added). Indeed, all of Scripture is to be brought to bear on questions of interpretation. “The infallible rule of interpretation of Scripture is the Scripture itself.” (WCF 1.9). The New Testament does not have overweening priority but is to be read in pari materia with the Old.

Therefore, I have little hope for this series. A more profitable exercise would be to pick cases and interpret Scripture from a Covenantal perspective as well as a Dispensational perspective. For example, take the Abrahamic Covenant as recorded in Genesis 17. Who will enjoy the blessings promised in this Covenant? When will they enjoy them? Where will they enjoy them? How long will they enjoy them? What Scriptural arguments do the sides bring to bear? Only through this type of exercise will you truly and fairly explore the differences between Covenant Theology and Dispensationalism.

JSB

Thanks for your comments, friends. The reason that the paper was not more extensive or technical, is that I simply wanted my congregation to have a better working knowledge on some of the main distinctions between the 2 camps. Thanks for reading:)!

Appreciate the background and wish you well. Although I know that you want your congregation to come away fully persuaded of Dispensationalism, I hope you will present a “flesh and blood” account of Covenant Theology and not a “straw man” version. I am afraid from your following statement that there will not be much meat on the bones of the Covenant Theology that you present.

The intent of this series of articles is not to fully flesh out the views of either dispensational or covenant theology, but to show the clear distinctions between them and why—Biblically—dispensational theology is to be preferred.

I do think that it was particularly helpful for you to identify that non-Dispensationalists can hold to amillennialism (which is really inaugurated millennialism), postmillennialism, or covenantal premillennialism.

By the way, I believe that James Montgomery Boice moved from pretrib premil to historic premil during his career. Heard him speak once at Tenth Presbyterian in Philadelphia back in the 1980s.

JSB

Like most people, I’ve been weaned on the “dispensationalism uses literal hermeneutics, and covenant theology spiritualizes things” approach. Of course it was much more nuanced than that, but this is the essence of it. This language probably isn’t helpful. The comments from Bro. Henebury’s on-going series illustrate this. Perhaps the time has come for a better terminology:

- Maybe all flavors of dispensationalists should use something like “authorial intent,” and stress how the original audience would have understood the OT passage.

- This leads us into how NT writers interpreted the OT. Peter’s use of Ps 16 comes to mind (cf. Acts 2).

But, as a better way forward, perhaps it would best to say that dispensationalists give primacy to the original author’s authorial intent, in the original audience’s context, rather than refer to “literal vs. spiritual.”

Tyler is a pastor in Olympia, WA and works in State government.

Authorial intent should be the goal of every endeavor to interpret Scripture. What else would one desire to know besides what the author intended to convey? However, claiming this as the proper term to describe dispensationalism is not helpful. It assumes that CT is not endeavoring to interpret according to authorial intent. From my experience, I that CT is equally committed to this concept, and perhaps even more so. I say more so because CT usually gives more attention to the genre of the book as an important aspect of accurate interpretation. The literal whenever possible hermeneutic frequently imposes literal interpretation upon a passage that the genre indicates should be understood symbolically. Poetry and apocalyptic literature should not be forced through a strictly literal hermeneutic. To do so distorts authorial intent instead of honoring it and submitting to it.

G. N. Barkman

Well, at least I tried to propose something useful! :)

Tyler is a pastor in Olympia, WA and works in State government.

Brothers, thanks for chiming in. Yes, I am seeking to be cautious with the phrase “literal interpretation” and recognize it is probably not the best phrase. Maybe a way of speaking clearly would be “consistently literal”, as often people’s hermeneutic changes drastically when it come to apocalyptic literature. I think a couple of the abuses we need to guard against in prophecy is assuming it is symbolic, as well as when there is symbolic language, to assume everything in the prophecy is symbolic.

We take the language in its normal sense, unless its normal sense makes no sense:) And yes, brothers, we pay specific attention to genre, as stated above…are we dealing with prophecy, proverbs, psalms, proverbs??

Perhaps a better way to describe to difference b/t the 2 camps, that both affirm literalness, would be our commitment to the DEGREE of literalness.

I think another caveat would be to include more in the article on perspecuity:)

Press on!

Look forward to the rest of the series. I realize you aren’t writing a journal article, here! Thanks for the series.

Tyler is a pastor in Olympia, WA and works in State government.

[TylerR]Look forward to the rest of the series. I realize you aren’t writing a journal article, here! Thanks for the series.

I agree with G. N. Barkman’s assessment of authorial intent but understand why, and appreciate that, Bros. Reardon and TylerR are struggling with how to address the difference between Covenant Theology and Dispensationalism when it comes to hermeneutical method. The struggle is because there is or should be no significant difference. The difference would lie in the application of the grammatical-historical method to a particular text. Perhaps Bro. Barkman, I, and others can provide constructive comments as the series proceeds which may help shed further light on this issue.

JSB

Why do Dispensationalists insist that the 1,000 years in Revelation 20 must be literal? By the time the term is first used in verse two, John has already given us five terms that are almost certainly symbolic. (key, bottomless pit, great chain, dragon, serpent) Symbolic in that the reality being communicated is something other than a literal key, etc. So what Biblical principle is violated if we at least consider the possiblity that the term, “a thousand years” is symbolic? After all, this is apocalyptic literature laden with symbols.

G. N. Barkman

I’m glad you asked an easy question … :)

We did a fairly deep-dive into Revelation 4-22 during family devotions last year. It took us four months. I found many dispensationalist commentaries a bit wild at some points. I think Robert Thomas’ 2-vol work is the most responsible thing out there from dispensationalists on Revelation. I look forward to preaching through Rev 4-22 one day. I’ve never seen it done in anything but a sensationalistic fashion.

Tyler is a pastor in Olympia, WA and works in State government.

From my experience, I that CT is equally committed to this concept, and perhaps even more so.

There are people like Peter Enns who flat out say that authorial intent of the OT doesn’t matter. I wonder if, in practice, that isn’t more prevalent that some might like to admit. For instance, when the OT talks about the land, it seems beyond dispute that the author had in mind the land of Palestine between the Euphrates and the river of Egypt. But there are a great many who deny that meaning for today and assert that it is eternity, the new heavens/new earth, or some such. Or take the NC. It seems clear from the words that Jeremiah intended that to refer to the ethnic Israelites. He certainly had the vocabulary and the categories to talk about the nations (as he, Isaiah, and other prophets do) and yet he didn’t. It was specifically Israel. He also clearly references the land of Palestine. Yet many today go beyond that intention or deny that intention on one or both counts. So I am not sure that CT as a whole is “equally committed” and I certainly wouldn’t say they are “more committed.”

I would add this caveat: There are many dispensationalists who came up with strange interpretations. Someone rather sardonically pointed out that the CT impulse was to spiritualize the prophetic sections while the DT impulse was spiritualize the historical narrative sections. There was a lot of good preaching, so to speak, that came from such nonsense.

The literal whenever possible hermeneutic frequently imposes literal interpretation upon a passage that the genre indicates should be understood symbolically. Poetry and apocalyptic literature should not be forced through a strictly literal hermeneutic. To do so distorts authorial intent instead of honoring it and submitting to it.

I object to this definition of “strictly literal.” A literal hermeneutic is one that reads/hears the author in his intent. So a “strictly literal” interpretation of an analogy or metaphor recognizes the analogy or metaphor. A “strictly literal” interpretation of poetry interprets it as poetry.

Here are three quotations that I think are helpful in this.

This recognition of a metaphorical style is not to be thought of as a return to allegorization, nor is it a “spiritualizing” of the passage. When a writer employs metaphor he is to be understood metaphorically and his metaphorical meaning is his literal meaning: that is to say, it is the truth he wishes to convey. The term “literal” stands strictly as the opposite of “figurative,” but in modern speech it often means “real,” and it is used this way by those who want to be sure that they know what the writer really and originally meant. In this sense a metaphorical saying is “literally” true. … Thus a metaphorical statement is “literally” true but cannot be “literalistically” true. The “literal” meaning, then, is what the particular writer intended, and although he used metaphor, no one familiar with the language in which he expressed himself could reasonably misunderstand him (Kevan, “The Principle of Interpretation,” in Revelation and the Bible, ed Henry, p. 294).

Dispensationalists claim that their principle of hermeneutics is that of literal interpretation. This means interpretation that gives to every word the same meaning it would have in normal usage, whether employed in writing, speaking, or thinking. It is sometimes called grammatical-historical interpretation since the meaning of each word is determined by grammatical and historical considerations. The principle might also be called normal interpretation since the literal meaning of the words is the normal approach to their understanding in all languages. … Symbols, figures of speech, and types are all interpreted plainly in this method, and they are in no way contrary to literal interpretation. After all, the very existence of any meaning for a figure of speech depends on the reality of the literal meaning of the terms involved. Figures often make the meaning plainer, but it is the literal, normal, or plain meaning that they convey to the reader” (Ryrie, Dispensationalism, p. 80).

The literalist (so called) is not one who denies that figurative language, that symbols, are used in prophecy, nor does he deny that great spiritual truths are set forth therein; his position is, simply, that the prophecies are to be normally interpreted (i.e., according to the received laws of language) as any other utterances are interpretation—that which is manifestly figurative being so regarded (Lange, Revelation, cited in Ryrie, p. 81).

So “literal interpretation” is authorial intent. It does not deny the use of metaphor, analogy, etc. It uses it.

[Larry]From my experience, I that CT is equally committed to this concept, and perhaps even more so.

There are people like Peter Enns who flat out say that authorial intent of the OT doesn’t matter. I wonder if, in practice, that isn’t more prevalent that some might like to admit. For instance, when the OT talks about the land, it seems beyond dispute that the author had in mind the land of Palestine between the Euphrates and the river of Egypt. But there are a great many who deny that meaning for today and assert that it is eternity, the new heavens/new earth, or some such. Or take the NC. It seems clear from the words that Jeremiah intended that to refer to the ethnic Israelites. He certainly had the vocabulary and the categories to talk about the nations (as he, Isaiah, and other prophets do) and yet he didn’t. It was specifically Israel. He also clearly references the land of Palestine. Yet many today go beyond that intention or deny that intention on one or both counts. So I am not sure that CT as a whole is “equally committed” and I certainly wouldn’t say they are “more committed.”

…………………………….

Just one quick thought on the land. Romans 4:13 says “For the promise to Abraham and his offspring that he would be heir of the world…” Since Jesus is the “offspring” (i.e., Christ - Gal. 4:16) it seems that there is an expansion of the promise. Israel as a nation received the land as promised with its little boundaries. And forfeited it. Now in Jesus, the obedient Israelite, the fuller intent of the promise is made known. A promise can be more than what a writer understood or anticipated. Why would “Israel” want Palestine when the world is now the inheritance?

I agree with GNB that “authorial intent” would be helpful to refer to, but it would solve absolutely nothing because what is meant by authorial intent can differ depending on one’s outlook. If one holds that the NT interprets the OT then what does “authorial intent” mean? Usually it means the intent of the Divine Author. But that begs the question that Divine intent is in agreement with that approach. I like the term “plain sense” to literal even though it isn’t perfect.

GNB loads the bases in another comment when he says we must judge meaning through genre. But this will play into the understanding of authorial intent which he recommended. Problem? Yes. The matter of genre is elastic to say the least, and especially in the area where GNB wants to commend his hermeneutics - i.e. apocalyptic.

Apocalyptic is a wax nose if ever there was one. I’ve read scores of descriptions (usually based on liberal scholarship) and they seldom agree. Neither can scholars agree on which books or parts of books are apocalyptic. And the Book of Revelation says it is a prophecy several times. It does not claim to be an “apocalypse” in the genre sense. It is an apocalypto because it is an unveiling, not a covering up. I reject treating Revelation or Daniel as apocalyptic. They are prophetic and they can be readily understood as prophecies in the “plain-sense” tradition, particularly via Biblical Covenantalism (I think).

As for “Land” and Romans 4:13, Paul is speaking about justification, not the land promise. I simply reproduce what I have written on SI before:

“If we look at Romans 4:13 your reasoning depends upon reading “world” (kosmos) as “planet earth” or “all the lands of the earth.” If such was Paul’s meaning then we could go with the amendments to Genesis 15 (although not without some difficulty regarding continuity). But this is not necessary because the Apostle does not have the land promise in mind in Romans 4. The context is justification to salvation, not Israel’s land grant. Even John Murray (Romans 141-142) recognizes this. A more recent commentator writes that,

“…in speaking about God’s promise, he [Paul] does not include any reference to the territorial aspect of the promise given to Abraham and to his descendants.” - R. N. Longenecker, The Epistle to the Romans, NIGTC, 510.”

But this illustrates the divide quite well. What seems reasonable to one group looks pretty outlandish to the other.

”

Dr. Paul Henebury

I am Founder of Telos Ministries, and Senior Pastor at Agape Bible Church in N. Ca.

Discussion