Languages and Your English Bible

Image

Many Christians are wrongly intimidated by the fact that they do not understand the original languages of the Bible. Those supposedly “in the know” make assertions that imply their superior status in understanding of Scripture because of their linguistic skills.

In reality, proper interpretation is more often about maintaining an open mind and avoiding logical fallacies. A believer who knows how to read and think, but doesn’t know the original languages, will be a superior interpreter to one who knows the ancient language but cannot think logically. Some highly educated folks cannot distinguish between correlation and cause, description and prescription, or the difference between partial truths and the whole truth.

The languages can make a difference, but not to the degree that some would imply. Muslims, for example, claim the only way to understand the Koran is to read it in Arabic. Christians, on the other hand, have traditionally not made such a claim. Snobs, by definition, would not make such an admission. Fortunately, most evangelical scholars are not arrogant; they will freely admit that understanding the original languages is helpful (otherwise why learn them?), but not absolutely crucial for every Christian.

Consider that the early Christians—for over three centuries—used the Greek translation of the Hebrew Old Testament (the Septuagint). When Paul lists the qualifications for elder in I Timothy 3, being fluent in Hebrew was not one of them.

For about 1,000 years, most Christians used Jerome’s Latin translation. For most of her history, the western church relied on this Latin translation. That is a long time.

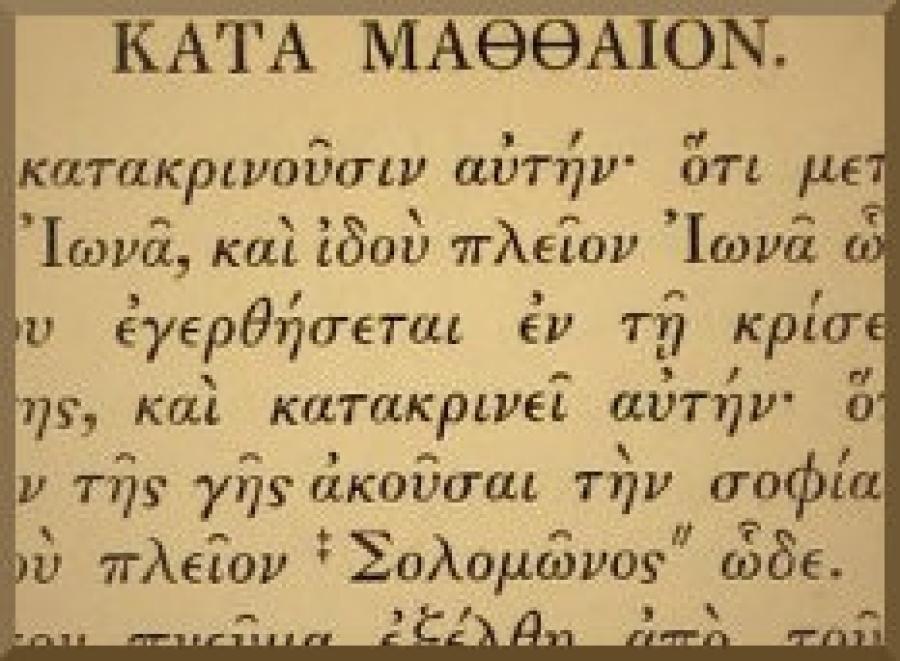

Still, God inspired the Old Testament in (mostly) Hebrew, and the New Testament in Greek. Yet we need to add a footnote or two. Early church tradition suggests that the Gospel of Matthew was originally written in Hebrew and later translated into Greek. Also consider that the words spoken by our Lord himself were spoken in either Mishnaic Hebrew or Aramaic (a language related to Hebrew). Thus, what we have in the Gospels are translations of Jesus’ words into Greek.

The New Testament authors often quote the Greek Septuagint (or sometimes their own translations from the Hebrew) with confidence as Scripture, not as merely an inadequate translation. Perhaps most mainstream Jews in the first century—who were not fluent in Hebrew—read the Greek Septuagint. After all, that is precisely why it was translated.

I think it is fair to say that the original languages are preferred and do add their nuances. We need scholars and biblical linguists. But the man in the pew should not feel intimidated at all. Whatever mainstream translation he owns is an accurate version of the original manuscripts for many reasons.

So why are there differences between translations? Are the original languages so rich that single English words cannot capture the meaning? Should we all purchase versions of the Amplified Bible to get the full meaning?

What most people do not understand is that it is English—not Greek or Hebrew—that is the rich language. The vocabulary of the English language has so many nuances—fine shades of meaning and a massive vocabulary. The reason for this is that English is combination and synthesis of several languages.

The original language spoken by the residents of England was Celtic. When the Anglo-Saxons invaded, they brought their German-like language with them, called “Anglish” which morphed into the word “English.” Much of our most common vocabulary words come from old German, and English is technically considered a low form of German.

When the Vikings conquered England, they brought their Scandinavian language to the party. So there might be a Celtic term, a German term, and a Scandinavian term for the same concept. Yet the plot thickened: when the Normans (from France) conquered England, they literally mandated the English people to adopt French as the spoken language. French, of course, is derived from Latin. So we picked up an entire array of French words (with Latin roots) that found their way into the English language.

The way we pronounced words changed, but we often retained the older spelling. For example, the words “light” or “rough” used to be pronounced exactly as they look. Hard to say unless you spray!

How does this apply to translation? Because English has so many synonyms and a vocabulary five times that of even modern German, we have to make a choice that Greek or Hebrew speakers did not have to make. What this means is that the ancient language vocabulary had to do more duty; thus their words were not as pinpointed as ours are, by and large. One word could mean more things.

Whereas other languages might have one word for “smile,” in English we must choose from: “smirk, beam, grin, sneer, grimace.” In both Hebrew and Greek, the single word for “spirit” can be translated as “wind, breath, or spirit.” We have three distinct words (if we do not include words like “breeze, draft, exhalation,” etc.).

In English, we can choose between the meek inheriting the “earth” and inheriting the “land.” It is our choice, because the original language can mean either one.

The amazing word for love in the Old Testament (hesed) can be translated as lovingkindness, steadfast love, mercy, or faithful love. The main New Testament word for love, agape, which can range in meaning anywhere from niceness (1 Corinthians 4:21) to the amazing love of God demonstrated for us in Christ’s death (Romans 5:8).

Regarding the use of agape in the Septuagint, Leon Morris explains that “it is most commonly used to refer to sexual love” (Testaments of Love, p. 102). He then points out that Christians (including Paul) later made the word agape special, giving it a meaning of sacrificial, others-centered love. If you think about it, we use the English word “love” in all those ways as well. The other important word for love (phileo) implies a brotherly love, but was also used for Jacob’s love of Esau’s stew (Gen. 27:4).

Even though all languages have flex in them (including English), we can communicate well in any and every language. In the case of translation, committees of top-ranked scholars do all major translations. Some were done so long ago that English has changed (as in the case of the Geneva and King James versions).

The modern, more literal translations—English Standard, New American Standard, New King James, Holman, etc.—are very well done. Dynamic translations—like the New International Version—generally capture the meaning well but lean a bit more toward paraphrase. Full blown paraphrases—like The Living Bible or The Message—are easier reading but not considered strict translations.

If you find variations between translations, however, they are often quite slight, usually based upon the choice of one of our abundant synonyms. In most instances, becoming fluent in Hebrew or Greek would not solve the problem.

The original languages have great value when it comes to nuance or understanding the options in the exceptional instances when a text is unclear. If you are a decent English speaker, your Bible is the dependably translated Word of God. Through becoming familiar with the text, study, debate, prayer, sitting under good teaching, and the work of the Holy Spirit, you can interpret well.

Ed Vasicek Bio

Ed Vasicek was raised as a Roman Catholic but, during high school, Cicero (IL) Bible Church reached out to him, and he received Jesus Christ as his Savior by faith alone. Ed earned his BA at Moody Bible Institute and served as pastor for many years at Highland Park Church, where he is now pastor emeritus. Ed and his wife, Marylu, have two adult children. Ed has published over 1,000 columns for the opinion page of the Kokomo Tribune, published articles in Pulpit Helps magazine, and posted many papers which are available at edvasicek.com. Ed has also published the The Midrash Key and The Amazing Doctrines of Paul As Midrash: The Jewish Roots and Old Testament Sources for Paul's Teachings.

- 6 views

Oops. Reference should be I Corinthians 4:21. Sorry about that. It reads (ESV):

What do you wish? Shall I come to you with a rod, or with love in a spirit of gentleness?

"The Midrash Detective"

Got that typo.

On the general topic, I have often encountered believers who sort of give up in the face of claims that are defended by appeal to original languages… when they know the claims are in error. They get flustered by lack of knowledge of Grk/Heb and don’t know how to answer.

But, as you pointed out, problems usually lie in the reasoning we do with Scripture.

I would add, as I have often counseled, that you can identify a false teaching 99% of the time simply by putting the verses being cited (or individual words) in context. The immediate context of the passage, the larger context of the writer’s teachings on the subject, the even larger context of the Bible’s teaching on the matter as a whole.

The error usually proves to be impossible to sustain in light of everything else the Bible says on the subject and subjects closely related to it.

I’ve also often counseled believers to be wary of any interpretation that rests solely on appeal to original language.

Views expressed are always my own and not my employer's, my church's, my family's, my neighbors', or my pets'. The house plants have authorized me to speak for them, however, and they always agree with me.

Pope, Netanyahu spar over Jesus’ native language

Pope Francis and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu traded words on Monday over the language spoken by Jesus two millennia ago.

“Jesus was here, in this land. He spoke Hebrew,” Netanyahu told Francis, at a public meeting in Jerusalem in which the Israeli leader cited a strong connection between Judaism and Christianity.

“Aramaic,” the pope interjected.

“He spoke Aramaic, but he knew Hebrew,” Netanyahu shot back.

[Jim]Pope, Netanyahu spar over Jesus’ native language

Pope Francis and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu traded words on Monday over the language spoken by Jesus two millennia ago.

“Jesus was here, in this land. He spoke Hebrew,” Netanyahu told Francis, at a public meeting in Jerusalem in which the Israeli leader cited a strong connection between Judaism and Christianity.

“Aramaic,” the pope interjected.

“He spoke Aramaic, but he knew Hebrew,” Netanyahu shot back.

There is a line of evidence suggesting that Jesus actually spoke Hebrew, albeit Mishnaic Hebrew with some Aramaic in it (eg., Bar for son instead of the Hebrew Ben). He probably also spoke Aramaic, but his teaching was probably in Hebrew. David Bivin has argued and demonstrated from 1st century documents that Hebrew was, in fact, spoken in Israel, and apparently commonly.

When Jesus is quoted in Aramaic in the Gospels, the reason it is preserved might be precisely because at that time he spoke Aramaic. It makes more sense to transliterate into Greek from Aramaic rather than translate in such cases. Mark 7:34 (ESV) is the prime example:

And looking up to heaven, he sighed and said to him, “Ephphatha,” that is, “Be opened.”

If Jesus always spoke Aramaic, why was this phrase chosen for transliteration?

"The Midrash Detective"

Makes sense, Ed. I hadn’t heard this idea before (that I remember, anyway) but it adds up. Netanyahu may have had it right after all.

Views expressed are always my own and not my employer's, my church's, my family's, my neighbors', or my pets'. The house plants have authorized me to speak for them, however, and they always agree with me.

Good article Ed. I find that the original helps me to ground my thinking better, but I must say that I have witnessed even Greek profs make poor decisions on the basis of forcing a primary or secondary lexical meaning onto a context. Really, it is the context which is decisive.

It has also been my experience that many students work very hard to acquire the languages, but at the expense of knowing their English Bibles well (let alone Theology). Men like Spurgeon, Lloyd-Jones, Stott and Dick Lucas in England told men to develop a workable grasp of the languages and learn to use the tools of scholarship. But they must know their Bibles!

Another little thought: modern scholarship analyzes the biblical languages to death. There is a real danger that in doing so they begin seeing things which aren’t there. E.g., just compare the exegetical studies by leading contemporary scholars and see how much disagreement there is in the use and prominence of terms. N. T. Wright says we have missed Paul’s meaning because we have filled our minds with 16th century categories. Ben Witherington, in his Romans Commentary, says the older exegetes are more reliable in their understanding of Greek than modern scholars. Then note the disagreement between the Porter/Carson school and the Fanning/Wallace school of verbal aspect. Anyway, this was worth reading.

Thanks.

Paul H

Dr. Paul Henebury

I am Founder of Telos Ministries, and Senior Pastor at Agape Bible Church in N. Ca.

Good thoughts, Paul, especially about studying languages to the neglect of fluency in the English Bible. I like that Ben Witherington, though I don’t always agree with him on every point. He can THINK. It is as though we love to rehash, but to actually think — imaginatively and creatively and especially logically — is a lost art.

"The Midrash Detective"

Discussion