The Great Race

During the 1960 Olympiad in Rome, an obscure Ethiopian named, Abebe Bikila, captured gold in the men’s marathon. The track-and-field world responded with collective incredulity: “What on earth is an Ethiopian doing in a marathon?” At that time the world’s premiere long-distance runners hailed from the cool climates of Northern Europe—the British Isles, Scandanavia, the Soviet Union. Bikila’s victory was widely dismissed as a fluke.

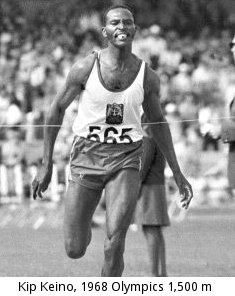

Bikila’s victory was no fluke. It turned out to be the spark that ignited a revolution. Just eight years later, no less than nine east Africans won medals in long distance races at the Olympics in Mexico City. Three Kenyans captured gold at those games, including a most inspiring victory by Kipchoge Keino.

Kip Keino arrived at the games suffering from a gall bladder infection. He ran anyway. Keino led the 10,000 meter race with only two laps to go when he collapsed and was disqualified. Two days later Mr. Keino ran again and won a silver medal in the 5,000 meter race.

With his gall bladder infection raging out of control, doctors sidelined Keino for the 1,500 meter race in which he had hoped to compete. Convalescing in the athlete’s village, Keino decided he would rather die than disappoint his fellow Kenyans. The fire to run burned too hot in his soul to quench. He hailed a cab and set out for the Olympic stadium. A mile from his destination, his taxi was stopped in its tracks by a gnarly traffic jam. In jeopardy of missing the race, Keino jumped out of his cab and jogged past stalled commuters to the stadium. He arrived in time and lined up against then world-record holder, Jim Ryun. Ryun had not lost a 1,500 meter race in over three years. Kip Keino won the race by 20 meters! [Ed.: Watch Keino’s victory here.]

The thunderous response that rocked Mexico’s Olympic stadium did not begin to compare with the fire Keino’s victory ignited in his fledgling and impoverished homeland of Kenya—particularly among Keino’s own Kalenjin tribe. Since that day, long-distance running has been a path to glory among the Kalenjin.

According to researcher, John Manners, 75 per cent of Kenya’s top runners hail from this single tribe. From 1987-1997 Kalenjin runners captured 40 per cent of the top international honors in men’s long distance running—including placing first, second, and twelfth in the Boston Marathon in 1996. “I contend” says Manners, “that this record marks the greatest geographic concentration of achievement in the annals of sport” (www.pewfellowships.org).

To this day a major long-distance race anywhere on earth will invariably find an east-African—if not a Kenyan—contending for the prize. Following the inspiring lead of Bikila, Keino and others have led the underdeveloped and thinly populated nation of Kenya to world-dominance in long-distance running.

Such stories tug at a yearning deep within our souls. A whole genre of movies seeks to tap this yearning: Chariot’s of Fire, Hoosiers, Rudy, The Rookie, Remember the Titans and Miracle spring to mind. But these stories of athletic conquest are only the shadow, not the substance of this longing in the human soul. Created in the image of God, we possess an inner drive to run life’s journey well. We want to know we are headed somewhere, accomplishing something of worth, overcoming all odds to live in triumph. In Chariot’s of Fire, British track star Harold Abrahams expresses this yearning memorably—however dysfunctionally. The night before his 100 meter Olympic race he says: “And now in one hour’s time, I will be out there again. I will raise my eyes and look down that corridor; 4 feet wide, with 10 lonely seconds to justify my existence. But will I?”

Abrahams’ anguished, “But will I?” illustrates the reality that our innate yearning to run life’s journey well is beset by the obstacles of a fallen world—troubled relationships, financial struggles, difficult circumstances, suffering, our own sins and failures. Such struggles can easily discourage us. Exhaustion sets in. You grow tired of running, tired of failing, tired of dealing with perpetual disappointment and the gnawing uncertainty as to where the journey is actually taking you. Am I living in steady pursuit of a worthy finish line or running on a tread mill? Focused determination is always in short supply where our vision of a worthy destination is clouded.

A wise man counseled me long ago through his writings to recognize that the first task of every soul is not to find its freedom, but to find its Master. Another counselor instructed me that the only life worth living is one unreservedly invested in a cause worth dying for. These two ingots of advice point inexorably to the imitation of Jesus Christ who embodied their truth (John 17:4; Hebrews 12:2). Jesus came to rescue sinners from the treadmill of self-centered worship by reconciling to God those who trust in Christ’s payment for sin (Romans 3:19-26). Once reconciled to our Master, believers join a tribe of runners on a path leading directly to God—the soul’s ultimate satisfaction and rest.

Inspired by the race Jesus ran right through death in dependence upon his Father, those reconciled to God through Christ have the joy of running life’s race with similar determination and hope. Self has been freed from self. Our souls are freed from the shackles of empty pursuits to run with blazing hope toward the open arms of God.

Pastor Dan Miller Bio

Dan Miller has served as the Senior Pastor of Eden Baptist Church since 1989. He graduated from Pillsbury Baptist Bible College in 1984 and his graduate degrees include the MA in history from Minnesota State University, MDiv and ThM from Central Baptist Theological Seminary and DMin from Trinity Evangelical Divinity School. Dan is married to Beth and the Lord has blessed them with four children: Ethan, Levi, Reed and Whitney.

- 9 views

I have always appreciated the way you think! This tapping into our yearning to run the race of life well, and, as Christians, to do so to God’s glory. Thanks, brother.

"The Midrash Detective"

Looking through the other lens, watching Jim Ryun lose the 1968 olympic 1500 meters was one of the most depressing sporting experiences of my life. Ryun actually ran a very good race, but Keino was fantastic.

Jeff Brown

JB

Discussion