Jesus Teaches the Old Testament: The Importance of Jewish Roots Studies, Part 1

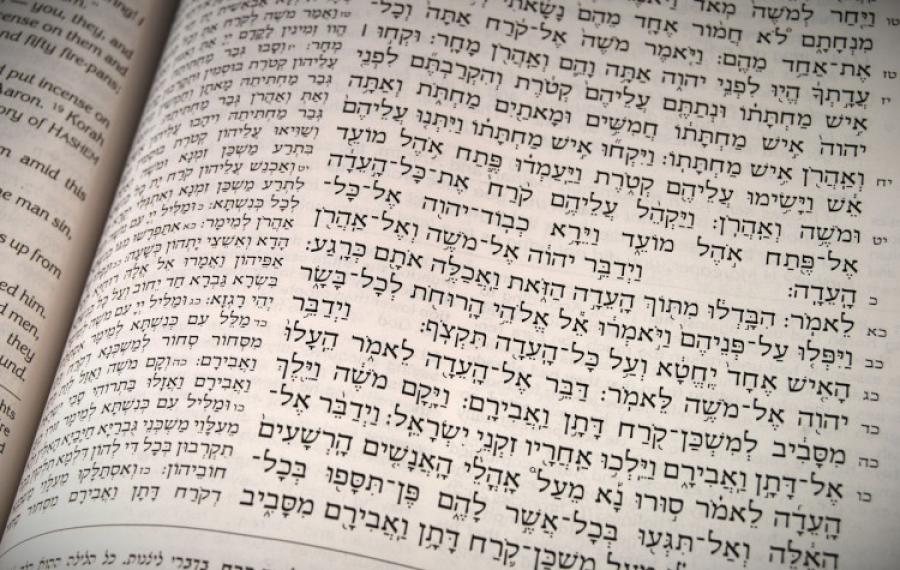

Image

What is the big deal about Jewish Roots? How can we better understand Jesus by examining the debates of His day? Why should we care if He derived some of His teaching from Old Testament passages?

The answer is simple: context. Jewish Roots studies can contribute toward increasing the Biblical context; when we increase context, we increase understanding.

As a conservative evangelical, I hold the Scriptures in high regard. My reverence for the Scriptures means I seek to interpret them fairly, using a method described by the term, “Historical-Grammatical.” Norman Geisler comments in The Chicago Statement on Biblical Hermeneutics:

This means the correct interpretation is the one which discovers the meaning of the text in its grammatical forms and in the historical, cultural context in which the text is expressed.1

If the reader agrees that historical and cultural contexts are helpful when it comes to interpreting Scripture accurately, we have answered the question as to why the Jewish Roots of Scripture matter; they contribute to the historical and cultural context of the New Testament.

Christians have historically embraced unflattering attitudes about Jewish Roots studies because of an anti-Semitic frame of mind dominating the Christian church for centuries. We should remember that even the Protestant movement blossomed in the soil of an anti-Semitic culture.

In modern times, some interpreters place little value upon Jewish Roots studies because they may over-emphasize a doctrine referred to as the Perspicuity of Scripture; you may know it by its simpler name: the Clarity of Scripture. Misused, this doctrine can minimize the importance of the cultural context of the Scriptures in general, not just Jewish Roots studies. Sometimes the doctrine of the Clarity of Scripture is invoked selectively and inconsistently.

I do believe the Scriptures are adequately clear when it comes to the major teachings of the Bible, but I also believe our understanding can be sharpened and honed beyond the merely adequate, and that increasing context — be it cultural or otherwise — can add insight toward interpreting a text more fully. I also believe the Jewish culture — more than other cultures (like Greek or Roman) — is particularly helpful, since this is the context of both testaments.

This is not to say that no Christians were interested in the Jewish Roots of our faith until after World War II. John Lightfoot’s work, “A Commentary on the New Testament from the Talmud and Hebraica” was published in 1658! The four-volume set includes his comments through 1 Corinthians. Due to his untimely death, the set was never completed.

Another commentator worth noting is John Gill (1697-1711). Like Lightfoot, Gill freely quotes or includes notes from the Talmud and other Jewish sources within his commentaries. Although few referred to Jewish Roots materials quite as frequently as these two, the latter 19th century saw a significant increase in Jewish Roots interest.

Others discovered an important concept we now refer to as “midrash” (a Jewish-style elaboration upon Scripture), though they did not use the term. By pouring over both testaments. Jonathan Edwards, for example, came upon a New Testament midrash developed from an Old Testament passage. In his book, The Religious Affections, Edwards ties the use of the Hebrew word “shibboleth” in Judges 12:5-6 to the teachings of Jesus.

In Judges 12, the word “shibboleth” was used to distinguish a regional accent during an instance of war. Northern Israelite impostors were sorted from their southern counterparts by the ability — or inability — to properly pronounce the word “shibboleth,” a word referring to the fruit (grain) of a crop.

Edwards writes,

As it is the ear of the fruit which distinguishes the wheat from the tares, so this is the true Shibboleth, that he who stands as judge at the passages of Jordan, makes use of to distinguish those that should be slain at the passages. For the Hebrew word Shibboleth signifies an ear of corn. And perhaps the more full pronunciation of Jephthah’s friends, Shibboleth, may represent a full ear with fruit in it, typifying the fruits of the friends of Christ…2

Since the word “shibboleth” means “fruit,” this connects us to Christ’s teaching that, “Thus, by their fruit [karpos, perhaps translated from the Hebrew shibboleth] you will recognize them.” To make this connection, one must accept that Jesus is taking an Old Testament teaching and applying it in a different way for His disciples.

When it comes to Biblical hermeneutics (the science of interpretation), the prime benefit of Jewish Roots studies is first and foremost (in my view) helping us to recognize midrash (or possible midrash) when we see it.3

While Jewish Roots studies help us discover midrashim, they offer a second benefit for the student of the New Testament: setting the broader context. When we discover what the major debates of the day were within the Judaism of the era (and perhaps the diversity of opinions about those debates), this can cue us in to what exactly Jesus (or Paul, etc.) is addressing in certain instances. This is not to say that the Roman or Greek cultures are not part of the context of the New Testament; they are. My viewpoint is that the Old Testament and the Jewish story line are the most important contexts. The division, however, is not a neat one: Greek and Roman culture wielded a significant influence upon first century Jewish culture!

Jewish Roots studies are important. In the next installment, I will (very briefly) summarize how Jewish Roots studies have risen to a greater prominence in portions of the evangelical world.

Notes

1 Chicago Statement on Biblical Hermeneutics, With commentary by Norman L. Geisler, www.bible-researcher.com/chicago2.html, accessed December 15, 2022.

2 Edwards, Jonathan, The Religious Affections, p.75.

3 Although I will elaborate further, by “midrash,” I mean a way of elaborating upon, interpreting, applying, our building upon earlier Biblical texts. My contention is that many portions of the New Testament are actually midrashim (plural of midrash) based upon Old Testament texts.

Ed Vasicek Bio

Ed Vasicek was raised as a Roman Catholic but, during high school, Cicero (IL) Bible Church reached out to him, and he received Jesus Christ as his Savior by faith alone. Ed earned his BA at Moody Bible Institute and served as pastor for many years at Highland Park Church, where he is now pastor emeritus. Ed and his wife, Marylu, have two adult children. Ed has published over 1,000 columns for the opinion page of the Kokomo Tribune, published articles in Pulpit Helps magazine, and posted many papers which are available at edvasicek.com. Ed has also published the The Midrash Key and The Amazing Doctrines of Paul As Midrash: The Jewish Roots and Old Testament Sources for Paul's Teachings.

- 775 views

There is so much to be derived from understanding Judiasm, and it’s like watching a flower open up. And I’m only getting started!

Aspiring to be a stick in the mud.

Ed,

I’m interested in learning more. However, as I understand this topic currently, understanding Jewish roots may provide interesting insights but it’s not always determinative to the meaning of a particular passage. In other words, understanding Jewish roots doesn’t change the meaning of a passage what we already know. Of course, second temple guys will disagree.

I hope to change your mind. IMO, it adds. The basic meaning doesn’t change. Kind of like the plagues in Exodus. Understanding the Egyptian gods they insulted doesn’t change the meaning, but adds a bit of depth.

"The Midrash Detective"

I have been preaching through the book of Genesis. It has been very enlightening to compare the scriptures with the Jewish oral traditions. I want to be careful not to elevate them to the place of scripture- especially when these oral traditions do not even agree among themselves at times. Still it helps to understand some of the conclusions that the people of Jesus time were coming to as they would have been highly influenced by these stories. It was fascinating to discover some of the oral history about Abraham, Nimrod, and Abraham’s father. It also helped me to better understand some of the theories about who Melchisidek was. I want to study that even more- especially with the stories about his virgin birth. I also want to study more about Abraham and the stars at his birth. The more I learn the more I understand why someone would want to be a Midrash detective.

JD Miller said:

“…Still it helps to understand some of the conclusions that the people of Jesus time were coming to…”

This is so true. There were a lot of fanciful stories and unsubstantiated beliefs that were common among the Jewish people. Especially noteworthy are those regarding the coming Messiah. It helps us know what influenced the original audiences, and clarifies some texts that might otherwise be puzzling.

"The Midrash Detective"

I learned about the story of a great star consuming the stars around it when Abraham was born and Nimrod becoming jealous and wanting to kill baby Abraham. The parallels to the birth of Christ are amazing. I cannot help but wonder if God was using a star as a sign in both instances in order to really get the attention of his people. Then I remembered that the wise men came from the east following the star. Jewish legends have Nimrod ruling in the east as the king of Babylon- the same place where Daniel prophesied of Jesus. There are a lot of clues for a detective to investigate.

JD Miller wrote:

I cannot help but wonder if God was using a star as a sign in both instances in order to really get the attention of his people.

This and the entire subject of the Gospel in the stars and legends about Nimrod are interesting. Although no longer considered reliable, The Two Babylons (by Alexander Hislop) was, at one time, quite popular. I personally think there is much reliable information in this classic, but its applications are often questionable (I am not sure they all relate to Roman Catholicism, although some may perhaps, like a blonde-haired Mary and the worship of mother and child). His take is that Nimrod was thought by those who revered him to be the fulfillment of the promise of the “seed of the woman” in Genesis 3:15, thus the Messiah.

Consider that Abraham’s seed was said to be like the stars of heaven, Joseph’s dream of the stars, sun, and moon bowing to him, and then Balaam’s prophecy in Numbers 24:17 about the star arising from Judah. Then you have baby Moses being marked for death as a baby, and, put into a melting pot, you can see all the constituent parts to this legend.

Nimrod lived earlier than Abraham, but legends don’t care about actual history! Also connected to all this is that amazing passage where I believe John sees the constellations become animated in Revelation 12:1-9. All so fascinating and sometimes inter-locking.

But you raise a good question: Does God use fictional beliefs embraced by a culture (in this case, the Jewish culture) to His ends? I think He does, but quite selectively (although I might be wrong about this). This is not God accommodating error by propagating error, but communicating in ways that would resonate with people (kind of like when the Ark was stolen and the strange things that happened to the Philistines that might make the Ark look like it was magical in I Samuel 4-6) based upon their pre-existent beliefs and understandings. This comes into play with Pentecost; the pre-existing (or perhaps later, we cannot be sure) legend was that when the 10 Commandments were given, God spoke them in the 70 languages of the nations in addition to Hebrew. Since the Day the Torah was given is also believed to be Pentecost, you can see how the Jewish audience would have compared it to the giving of the Law. But this legend is recorded later than the Acts 2 Pentecost, but is possibly an older legend that was recorded later (something not unusual in the Jewish culture of the time).

"The Midrash Detective"

Discussion