Sacred Desk or Sacred Cow? Perspective on the Pulpit (Part 1)

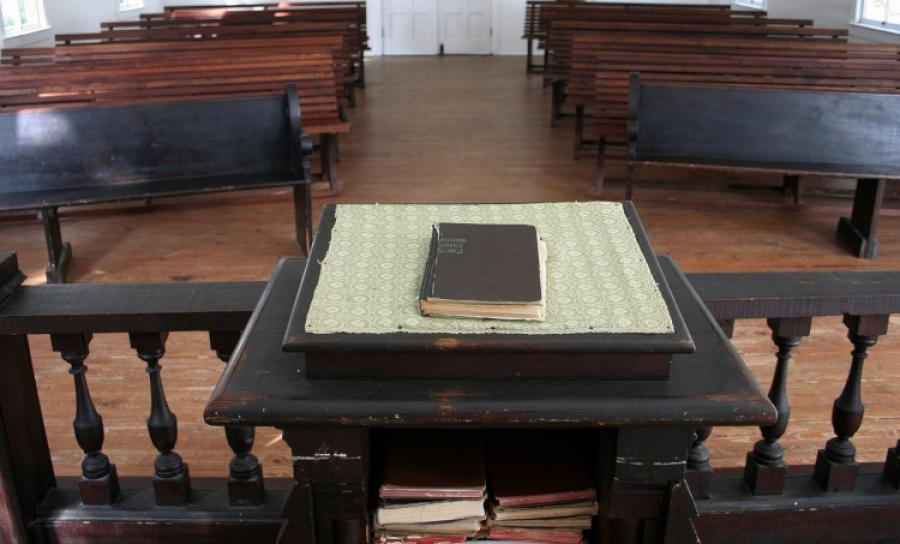

Image

Since the days of the Reformation, Protestant churches have traditionally situated the pulpit front and center in the architecture of their meeting places. The purpose of the pulpit’s conspicuously elevated and prominent position is to symbolize the authority and centrality of God’s Word in the life and ministry of the gathered church. The question we want to raise in this brief article is whether such symbolism is always necessary or helpful in our day.

Origins of the “Pulpit”

The English term “pulpit” derives from the Latin pulpitum, which originally referred to a raised platform on which a speaker would stand. This usage is seen in the Authorized Version’s translation of Nehemiah 8:4: “And Ezra the scribe stood upon a pulpit of wood, which they had made for the purpose.”1 To my knowledge, this is the only time the English term is used in the Bible.

The next extant reference to a “pulpit” doesn’t occur again until the third century A.D. Cyprian, Bishop of Carthage, uses the term pulpitum to refer to a physical structure within a church building. According to Michael White,

The term seems to refer to a slightly raised dais or platform at one end of the assembly hall where the clergy sat. In once instance the honor of ordination is symbolized in ascending the pulpitum in the loftiness of the higher place and conspicuous before the whole people. The phrase “to come to the pulpitum” even becomes the technical term for the ordination of a reader in the church at Carthage.2

Later, in the fourth century, mention is made of Chrysostom reading and preaching from the ambo,3 which was a small desk usually elevated on a platform. Initially, the ambo was located in the front and center of the sanctuary, but by the ninth century it was moved to the side in order to make room for the altar of the Eucharist.4

With the advent of the Protestant Reformation and its emphasis on the ministry of the Word in corporate worship, the ambo or, as we now know it, the pulpit, was repositioned to a more central and prominent place in the sanctuary.5 What’s more, large pulpits were constructed in order to make the minister look smaller and thus to magnify God’s Word. The elevation of the pulpit above the congregation not only enabled the preacher to see the people but also signified the authority of Scripture over God’s people.6 This tradition persists in many Protestant churches today.

The Pulpit as “Symbol”

As noted above, Protestants have traditionally viewed the pulpit (or lectern) as more than a mere piece of furniture. It is viewed as an important symbol. Reformed authors D. J. Bruggink and C. H. Droppers argue, “Because we preach and celebrate the Sacraments at the command of our Lord, the furniture which we use to obey his command inevitably becomes a reminder, a symbol, of that Christ-commanded action.”7 Accordingly, they assert,

To set forth the God-ordained means by which Christ comes to his people, the Reformed must give visual expression to the importance of both the Word and Sacraments. Because the Word is indispensable, the pulpit, as the architectural manifestation of the Word, must make its indispensability clear.8

Indeed, failure to give architectural prominence to the physical pulpit is viewed by some, especially those in the Reformed tradition, as a downward trend among evangelical churches today. Jon Payne, a Presbyterian minister, attempts to trace the diminishing of the pulpit to the revivals of the Second Great Awakening and the “New Measures” introduced by Charles Finney. The emphasis, according to Payne, shifted from worship to evangelism. And, as a result,

Stages with small removable pulpits replaced fixed, central, and elevated pulpits; sloped amphitheatre-like seating which put the congregation above the pulpit replaced flat surfaced seating where the congregation was physically (and symbolically) under the Word; pipe organs, choirs, and ostentatious stained glass became the focal point of the congregation rather than the centralized pulpit and the illuminating light shining through clear windows.

The same author goes on to lament that “most contemporary sanctuaries could literally be transformed overnight into movie theatres or Broadway playhouses.”9

The Pulpit as “Circumstance”

Despite the venerable Protestant and Reformed tradition of “pulpit as symbol,” we cannot endorse that tradition as a biblical mandate or an essential feature of church architecture. Nor should we assume that churches using smaller portable pulpits or those not using one are necessarily depreciating the centrality of the Word in church life and ministry.

There’s no command in either the OT or NT requiring the use of a pulpit. The erecting of Ezra’s platform (Neh 8:4) was prompted by practical exigency rather than divine precept. In the synagogue Jesus stood to read the Scripture but sat down to expound the Scripture (Luke 4:16-21). In fact, it seems Jesus did much of his teaching in a seated posture (Matt 5:1; 13:2; Mark 9:35; Luke 5:3; John 8:2). The apostle Paul stood both to read and to preach the Scripture in the synagogue (Acts 13:14-41). But we have no evidence that the apostles or the Lord Jesus used what we know as a “pulpit.”

To use a theological distinction common to the Reformed tradition, the proclamation and teaching of God’s Word is an “element” of worship. That is, it’s an essential feature of corporate worship and ministry. On the other hand, a physical pulpit or lectern is not an “element” of worship but simply a “circumstance.” Accordingly, the use or non-use of a pulpit is based on practical expediency not on biblical precept, precedent, or principle. In most cases, a pulpit serves as a place on which the preacher or teacher may place his Bible and notes. But in the last analysis, the use, size, and location of a pulpit is a matter of liberty and utility.10

Keeping the distinction between “element” and “circumstance” in view is part of what enabled C. H. Spurgeon, the “Prince of Preachers,” to be critical of most Protestant pulpits while still affirming the centrality of preaching. Indeed, Spurgeon complained that many oversized pulpits undermined rather than enhanced good preaching. In discussing the importance of posture and gesture in preaching, he notes,

Pulpits have much to answer for in having made men awkward. What horrible inventions they are! If we could once abolish them we might say concerning them as Joshua did concerning Jericho—”Cursed be he that buildeth this Jericho,” for the old-fashioned pulpit has been a greater curse to the churches than is at first sight evident.11

Sacred Desk or Sacred Cow?

In this writer’s opinion, elevating the status of pulpit furniture to a divinely sanctioned symbol is not only unwarranted but also unwise. The only divinely sanctioned symbols for the New Covenant church are Baptism and the Lord’s Supper. Promoting the pulpit as a divinely sanctioned symbol blurs the distinction between the truly symbolic means of grace and the non-symbolic means of grace. While churches are at liberty to incorporate images of the cross or other Christian emblems into the architecture of their buildings, they should beware of according these “symbols” some kind of biblical or quasi-biblical necessity.

But for some what was once called “the sacred desk” has evolved into a kind of “sacred cow.” The thought of replacing the older, larger, and stationary pulpit with a newer, smaller, and portable pulpit is treated as a serious downgrade. Less extreme advocates of preserving the Protestant and Reformed “pulpit tradition” are more restrained in their judgment. They acknowledge that the pulpit is technically just a circumstance of worship. Nevertheless, even their more moderate attachment to the old wooden pulpit can leave them resistant to change. It can also incline them to suspect those advocating change of a subtle movement away from the primacy and centrality of the Word. Yet, if I may borrow and adapt the words of Meredith Kline,

Heresy in this matter does not consist in the size or locality of the pulpit. The heresy is insisting that the pulpit must be a certain size and be placed in a particular spot. Indeed, heresy is insisting that a physical pulpit must be used at all.12

I’m not necessarily advocating a kind of pulpit “iconoclasm.” Of course, if one’s congregation were venerating the old sacred desk in the way the Israelites of old were making an idol of the bronze serpent (2 Kings 18:4), he may need to reduce that piece of furniture to splinters and sawdust. But most Reformed congregations haven’t reached that point.

Nor am I suggesting that every church must or necessarily should replace their grand old pulpit with a newer portable lectern. If the older pulpit is serving well the needs of the preacher and the congregation, there may be no need for change. There may be a need, however, for some teaching that, figuratively speaking, “puts the old pulpit in its proper place,” that is, as a mere circumstance of worship.

Notes

1 This is also found in the Geneva Bible (1560). Interestingly, the Latin Vulgate employs the phrase gradum ligneum, i.e., “wooden step.” Most modern versions correctly translate the Hebrew phrase אץ מגדל as “wooden platform” (NIV, NET, ESV, CSB).

2 “The Social Origins of Christian Architecture,” Harvard Theological Studies 42 (Valley Forge, PA: Trinity Press International/Johns Hopkins University Press, 1990), 2:23, as cited by Kenton Anderson in “The Place of the Pulpit”; accessed Dec 17, 2012 on the Internet: http://www.preaching.org/the-place-of-the-pulpit/.

3 The Latin ambo derives from the Greek αμβων, which refers to a desk or lectern.

4 See Victor Fiddes, The Architectural Requirements of Protestant Worship (Toronto: Ryerson Press, 1961), 29-30, as cited by Kenton Anderson.

5 Fiddes, 42-43.

6 See Rebecca VanDoodevaard, “Ecclesiastical Architecture (2)” accessed Dec 17, 2012 on the Internet: http://thechristianpundit.org/2012/04/27/ecclesiastical-architecture-2/; and Jon D. Payne, “Thoughts on Ecclesiastical Architecture” accessed Dec 17, 2012: http://grace-pca.net/thoughts-on-ecclesiastical-architecture.

7 Christ and Architecture (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1965), 457, as cited in Meredith Kline’s “Symbols, Structures, and Scripture,” The Presbyterian Guardian 35 (1966), 74-75; accessed Dec 17, 2012 on the Internet: http://www.meredithkline.com/klines-works/articles-and-essays/symbols-st….

8 Ibid.

9 Payne, “Thoughts on Ecclesiastical Architecture.”

10 Meredith Kline is correct when he asserts, “The plain fact is that church worship has no necessary connection with an architectural structure of any kind or with any furniture, whether pulpits, tables, or fonts. Judgments on matters of church architecture, as on all other cultural adjuncts (i.e., “circumstances”) of Christian worship, properly proceed from the recognition that what the Scripture has not prohibited is lawful, though not always expedient.” “Symbols, Structures, and Scripture.”

11 Cited from chapter 19 of Lectures to My Students where Spurgeon is explaining the importance of posture, action, and gesture in preaching. Lectures to My Students (Repint, Zondervan, 1972), 276. The reader can also access the relevant section on the Internet here: http://www.spurgeon.org/s_and_t/pulpits.htm (accessed Jan 31, 2013).

12 Kline was addressing that argument that the pulpit must occupy a central place in the sanctuary. His actual words: “Heresy in this matter does not consist in placing the pulpit in an inconspicuous corner rather than in some central spot. The heresy is insisting that there is any particular spot where the pulpit must be placed.” “Symbols, Structures, and Scripture.” His use of the word “heresy” may be a little strong though its NT usage can accommodate less serious sorts of sectarian teachings or practice (see Acts 15:5; 26:5; Gal 5:20).

Bob Gonzales Bio

Dr. Robert Gonzales (BA, MA, PhD, Bob Jones Univ.) has served as a pastor of four Reformed Baptist congregations and has been the Academic Dean and a professor of Reformed Baptist Seminary (Sacramento, CA) since 2005. He is the author of Where Sin Abounds: the Spread of Sin and the Curse in Genesis with Special Focus on the Patriarchal Narratives (Wipf & Stock, 2010) and has contributed to the Reformed Baptist Theological Review, The Founders Journal, and Westminster Theological Journal.

- 521 views

The other pastor and I now preach sermons TOGETHER half the time, and interact together as we preach a text. During these times, we move the pulpit and sit together at a table on the platform. No pulpit.

Tyler is a pastor in Olympia, WA and works in State government.

….but that does not mean that the presentation of the Word necessarily ought to rely on one person alone, does it? One thing that I’ve really liked when I visit my grandmother’s somewhat evangelical Methodist church is the Scripture readings—generally a Gospel, New Testament, and an Old Testament reading. The sermon is then appropriately shortened to leave time for music (ministry of the Word in song) and the rest. It’s not a perfect situation—the church is in a position where they need to accept lay preachers instead of someone trained—but the weekly readings give parishioners an idea of the breadth of Scripture while the sermons point to the depth.

What I’ve seen is that when the pastor is the major source of Scripture, and is required to do so for 45 minutes and up, a lot of them don’t really exegete the Scripture, but rather they fall back on the pet theological stances they learned in Bible college. So in my view, it’s a good idea to spread the ministry of the Word beyond just the pastor and the pulpit.

Aspiring to be a stick in the mud.

Bob’s articles are always great. He is addressing something that is starting to become prominent in the Reformed circles which is a refocus on the pulpit (and also the sacrament table). The concern I have seen is a veneration of the pulpit and other things. What I am starting to see in the Reformed circles is a bit of what we struggled with in Fundamentalism, which is putting and emphasis on something that is not required in Scripture. A number of reformed churches are starting to throw out their pulpits and replace with larger more grander pulpits and are replacing their communion tables with larger tables that look more like dinning room tables. And they are beginning to preach or call out those who do not follow this practice. Bob is rightly calling them out on this. Nothing wrong with a large pulpit, but it is the thinking behind it that counts and that we need to be careful with.

I think the trend in most evangelical churches today is the shift of the focus from the pulpit, and hence preaching the word of God, to musical worship and singing as the way to interact with God.

It is shocking to hear people say the main thing they get out of a Sunday service is the singing. Some (like my in-laws) think the worship IS THE MAIN THING. They’ve abandoned preaching as being important. Bible study groups, they think, can readily replace preaching.

Our church doesn’t struggle with pulpit idolatry, but we have had struggles with removing crosses from walls and classrooms in our church.

The argument is that removing the cross from a classroom or wall in the church is somehow de-emphasizing Christ’s atoning sacrifice.

We have a large cross that hangs on the wall behind the pulpit in the auditorium. There’s been some talk about removing it to make better use of the stage. However, I know that will cause significant consternation to many of our older congregants. It’s like taking Christ out of the church.

Right. It is. But worship, properly understood, is more than music. Listening to the preaching of the Word with reverent attention, and receiving its teaching with faith IS worship, as is public prayer and giving.

The problem is that we’ve allowed “worship” to be defined as praise in singing, and that’s only a small part.

G. N. Barkman

I guess I’m getting close enough to the age where I’d also be considered one of the “older congregants” in my church. It’s certainly true that there’s nothing that says a church sanctuary needs to look the part, and I can’t see that there’s anything unbiblical about it looking like a gymnasium, a movie theater, or even a ball field. But I believe there’s still something to be said for decorations/touches/whatever you want to call it that can enhance the overall climate of worship and help to put one in the right frame of mind. In my mind, this is not that much different from having the instrumentalists play before the service, or having a moment of silent prayer to help clear our minds (neither of which is also required).

Having a cross at the front is one of those things. We don’t worship it or venerate it, but it does help to remind those in the building about the activities that take place there that should be all about worshiping our God, even when the activity is not specifically a worship service. And having worshiped in a number of churches that have a cross at the front, I know from experience it’s not all that hard to have a divider or screen that can be lowered in order to use the building in a different way. It’s not even that hard to hang the cross in such a way that it can be temporarily removed and hung back up later.

Even though I can’t say it would be wrong to make our worship spaces completely utilitarian or simplistic without any decoration at all, I still feel that something intangible but valuable would be lost by doing so.

Dave Barnhart

Regarding crosses in the church, the German word “Bildung” comes to mind. It means “education” today, but is derived from “Bild”, or “picture.” The story I was told was that back in the days when most people were illiterate, one of the teaching methods used was to walk people through the church and explain to them what each picture or statue represented. So looking at the “Bilder” became “Bildung”, literally “picturing”, and hence education.

Now most of our members are pretty much literate these days, but we yet receive a lot of information visually, and we might wonder whether the placement of those crosses (or whatever) yet fills a very important need. We could praise God in a bare room—plenty of people have—but the flip side is that various factors reach our hearts and minds by appealing to our senses. Our question is not whether there should be visual cues pointing at the Gospel, but rather what they should be, and how well they work.

(and to build off my previous comment, it also means that the decoration committee can interestingly take a little bit of the load off the pastor, in the same way as Bible readings can)

Aspiring to be a stick in the mud.

Like Bob states in his article above, a lot of this is being driven by the younger reformed groups (“cage stagers”). We have them at our church. They want to take down the cross, or get rid of a Sunday School picture, but they are totally okay with having Calvin on their backpack or having 1517 tatooed on their arms. The folly of youth!

Discussion