Legalism & Galatians Part 3: Adoption

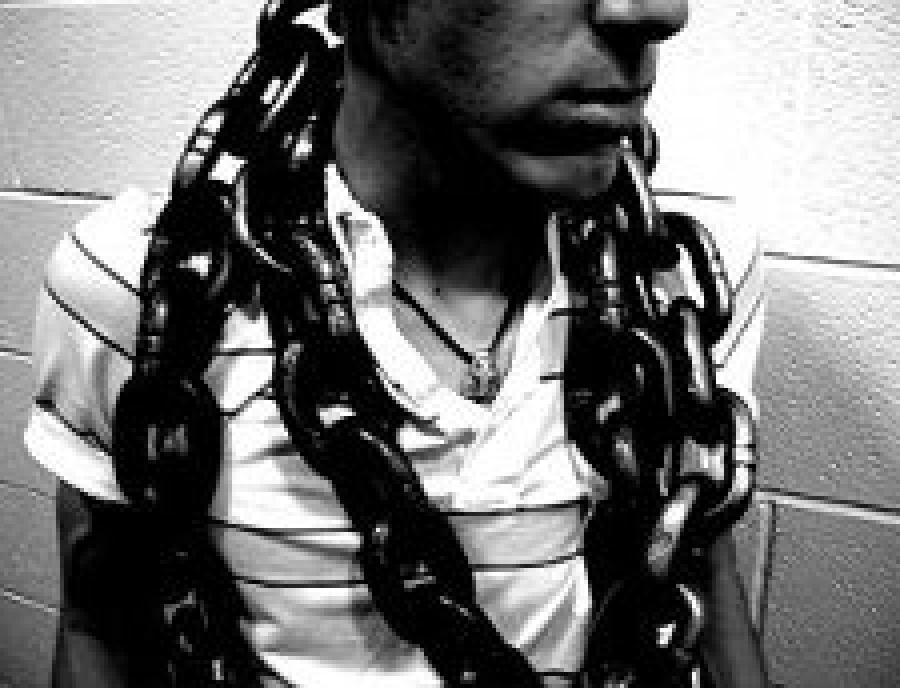

Image

Portions of the epistle to the Galatians have been used in a manner that breeds confusion and misunderstanding regarding legalism, grace, sanctification, and Christian living. It’s a pity, because the epistle speaks powerfully and clearly on all of these topics. The book’s teaching on adoption is an especially potent message for our times, carving a clear, joyful—yet responsible—path between the opposite errors of justification by works (legalism) and sanctification without works (antinomianism).

But that’s not all. The reality of believers’ adoption as God’s children not only answers the extremes of legalism and antinomianism, but also counters other common errors. Here, we’ll consider two additional errors as well as the two opposite extremes.

1. Adoption calls us away from the false gospel of justification by works.

I’ve made the case previously that the primary error Galatians was written to address was a false gospel of justification by works (Gal. 1:6-7) that had been brought to the Galatian churches by outsiders who did not know Christ (Gal. 1:8-9, Gal. 1:12) and, in reality, cared as little about observing the Law of Moses as they did about the saving death and resurrection of Christ (Gal. 6:12-13).

So the letter offers multiple, distinct arguments against this false teaching and those who advocated it. The adoption teaching (Gal. 4:1-11) is one of these arguments.

In 3:19-29 Paul had explained that the purpose of the Law never was justify anyone and that its purpose was temporary, didactic, and protective—in a role subordinate to “the promise” through Abraham. The thrust of that argument was that the Abrahamic promise (“in you all he families of the earth will be blessed”) is actually a reference to Christ (see Gal. 3:16-18) and provides justification through faith alone (Gal. 3:22-24). The Law was “added” (Gal. 3:19) to help believers in various ways until Christ came.

The apostle mentions the reality of adoption in Galatians 3:26, then returns to it in 4:1-11, emphasizing that adoption (through faith) makes any “return” to efforts to achieve justification through works especially out of place.

So you are no longer a slave, but a son, and if a son, then an heir through God. Formerly, when you did not know God, you were enslaved to those that by nature are not gods. But now that you have come to know God, or rather to be known by God, how can you turn back again to the weak and worthless elementary principles of the world, whose slaves you want to be once more? You observe days and months and seasons and years! I am afraid I may have labored over you in vain. (ESV, Gal 4:7-11)

The logic is clear. If we are God’s sons and daughters through faith alone, we are accepted by Him graciously without any reference whatsoever to our works. Any move toward making our position before God contingent on doing something is both absurd and insulting.

And because you are sons, God has sent the Spirit of his Son into our hearts, crying, “Abba! Father!” So you are no longer a slave, but a son, and if a son, then an heir through God. (Gal. 4:6-7)

Some of the details of Paul’s language are too important to brush by here. What were the Galatians trying to “return” to? The apostle characterizes their pre-Christian experience as one of captivity to “the elementary principles” (Gal. 4:3) and the “the weak and worthless elementary principles of the world” (Gal. 4:9). He associates these principles with observing “days and months and seasons and years” (Gal. 4:10).

Is he referring to Mosaic law, then? Yes and no. Galatians 4:8 provides a vitally important bit of context: “you were enslaved to those that by nature are not gods.” Before Christ, the Galatians were mostly polytheists—pagans. Worship of these false gods would have involved days, months, seasons, etc. But because the false teachers in the region were teaching believers to seek justification through parts of the Mosaic law, the days, months, and seasons in 4:10 were Mosiac.

If we let that sink in a moment, we realize Paul is saying that both pagan rituals and Mosaic rituals were, in the case of the Galatians, expressions of the same “elementary principles”—the same slavery to works-based salvation. The gods involved were different, but in both cases, the ritual efforts were viewed—foolishly and vainly—as a means of acceptance by the deity.

The implication is sobering. Regardless of where the rules come from, viewing them as a means of justification before God (or gods) is pagan and idolatrous!

In context, the gross inappropriateness of going that direction is intensified by the fact that believers are adopted children of God—sinners brought graciously into His family at His (very great—Gal. 4:4) expense, not ours!

2. Adoption calls us away from quasi-legalism as well.

If our position as graciously adopted Children of God calls us away from justification by works, it certainly also rejects the notion that we may retain, or somehow enhance, our family status through works (much less by multiplying strict, often poorly-conceived rules). Further, this gracious adoption calls us to rest in the assurance that nothing we do or fail to do can remove us from this family.

For you did not receive the spirit of slavery to fall back into fear, but you have received the Spirit of adoption as sons, by whom we cry, “Abba! Father!” (Rom. 8:15)

See what kind of love the Father has given to us, that we should be called children of God; and so we are. (1 John 3:1)

In love he predestined us for adoption as sons through Jesus Christ, according to the purpose of his will (Eph. 1:5)

At this point, those who know their New Testament well feel some tension: “But wait—aren’t the children of God required to work hard in His service (Php. 2:12, 1 Cor. 9:27) and live in fear (1 Pet. 1:17)?” More on that later. It’s important at this point, to see the unchangeable security of our adoption and bask in that (Matt. 11:28-30).

3. Adoption calls us away from subjectivism.

Pondering the fact of our gracious adoption as God’s children should also drive away another common distortion of the Christian life: subjectivism. I use the term here for portrayals of Christian living and sanctification that heavily emphasize—either directly or by implication—how we feel about our standing with God.

As an example of what I mean, pulpit and devotional rhetoric on John 15’s calls to “abide in” Christ, and Romans 6’s appeals to “know,” “reckon,” and “yield” often subjectivize our relationship with God by defining these activities in a way that is, ultimately, emotional. Some are quite transparent on this point, challenging hearers or readers to ask themselves “How close do you feel to God?” and the like.

Others subjectivize by a process of elimination: they systematically reject definitions of “abiding,” etc. that focus on faith and obedience, so that pretty much all that’s left is holy warm-and-fuzzy feelings.

If I can be frank, this is no better than the quasi-legalism of thinking that our standing with God is enhanced by multiplying hard work and/or rules. In both cases, we view our acceptance by God as something incomplete, insecure, somehow enhanced by either doing the right deeds or feeling the right feelings.

But neither what I do nor what I feel have any bearing whatsoever on my status as a fully adopted and accepted child of God. Adoption comes to us once-and-forever through faith in the promise of God.

4. Adoption calls us away from antinomianism and its cousins.

It should not be difficult to see that our gracious and unalterable status as adopted children of God brings responsibilities. Unlike many human families, our conduct or emotions do not result in our Father loving us less or more. But, as in human families, sonship does bring responsibilities and varying degrees of harmonious fellowship (1 John 1:6-9).

With respect to our righteous status before God the Judge, we are credited with Christ’s righteousness and utterly free of judgment and fear of judgment (1 John 4:18). With respect to our relationship as sons and daughters, our conduct is pleasing or displeasing in varying degrees to our loving Father. And so we find that Scripture frequently connects sonship with a sobering sense of responsibility.

Therefore be imitators of God, as beloved children. And walk in love, as Christ loved us and gave himself up for us, a fragrant offering and sacrifice to God. (Eph 5:1–2)

for at one time you were darkness, but now you are light in the Lord. Walk as children of light (for the fruit of light is found in all that is good and right and true), and try to discern what is pleasing to the Lord. (Eph 5:8–10)

and I will be a father to you, and you shall be sons and daughters to me, says the Lord Almighty.” Since we have these promises, beloved, let us cleanse ourselves from every defilement of body and spirit, bringing holiness to completion in the fear of God. (2 Co 6:18–7:1)

Aaron Blumer 2014 Bio

Aaron Blumer, is a Michigan native and graduate of Bob Jones University and Central Baptist Theological Seminary (Plymouth, MN). He and his family live in small-town western Wisconsin, not far from where he pastored Grace Baptist Church for thirteen years.

- 22 views

[The Article] 2. Adoption calls us away from quasi-legalism as well.No matter how many good works we do, the identity we make for ourselves will never even approach the excellence of the identity Christ earned and gave us.

If our position as graciously adopted Children of God calls us away from justification by works, it certainly also rejects the notion that we may retain, or somehow enhance, our family status through works (much less by multiplying strict, often poorly-conceived rules). Further, this gracious adoption calls us to rest in the assurance that nothing we do or fail to do can remove us from this family.

Balanced emphasis is hard to maintain… there’s always that human pull toward “what’s easier,” and oddly enough even legalism/quasi-legalism is easier in some ways than the “rigorous resting” depicted in the NT. It’s easier on the intellect, because it’s easier to understand. It’s also easier on the human pride.

Of course, anti-nominianism and its cousins is way easier in certain ways also.

But on the whole, even though Jesus depicted discipleship as a very demanding struggle, He spoke the truth when He said his burden was light. Because nothing is heavier and harder in the long run that trying to earn your own standing before God/earning His personal approval. Anyone who goes after that with seeing eyes, sees increasing despair of ever accomplishing it.

The alternatives/imbalances only seem easier.

Views expressed are always my own and not my employer's, my church's, my family's, my neighbors', or my pets'. The house plants have authorized me to speak for them, however, and they always agree with me.

[Aaron Blumer]“Easier on pride” is an interesting phrase. If one believer, on the basis of his life of goodness and good works, thinks he is a better Christian, more deserving of being a child of God than his brother, then he has pride. He is comparing himself with his brother in a prideful way. But he has a worse sort of pride. He is thinking that by being good he has somehow made for himself an identity that is more compelling, more deserving of child-of-God status than the identity Jesus earned and gave each of us. So quasi-legalism, as you put it, is pridefully holding oneself above not just your brother, but God.Balanced emphasis is hard to maintain… there’s always that human pull toward “what’s easier,” and oddly enough even legalism/quasi-legalism is easier in some ways than the “rigorous resting” depicted in the NT. It’s easier on the intellect, because it’s easier to understand. It’s also easier on the human pride.

…

Yes… there is also the pride of self effort. I wrestle with the concept… still not entirely clear to me where this crosses over into sinful expression. There’s a certain independence of spirit that says “I got myself into this mess and I’ll get myself out of it” that is healthy to a point. I’m reminded of the little toddler who is struggling to tie his shoes, and when you offer to help he pulls away and says “I can do it myself!!” … when quite often he definitely can’t.

But the “I’m going to learn to solve my own problems” part is good to a point. A sense of responsibility. But when it comes to solving the problem of our relationship with God and the sin that prevents it, it’s hard to let go of the idea that we should be responsible to solve it ourselves. That kind of pride… a misapplied version of something that is somewhat healthy in itself…?

Views expressed are always my own and not my employer's, my church's, my family's, my neighbors', or my pets'. The house plants have authorized me to speak for them, however, and they always agree with me.

About a toddler insisting on tying his own shoes - my son loved to do that, and ended up with a tight knot that I had to work to untie. There’s a lesson about our desire to be self-sufficient, we want our own wisdom to work. We wrongly want our wisdom to be effective. But it isn’t. We must admit our wisdom is not wise, and renew our minds; we must repent of our thinking and think His thinking.

––-

I get what you’re saying about the effort we put into our Christian walk. But I think we also need to maintain the attitude of 1 Corinthians 4:7 “What do you have that you did not receive? If then you received it, why do you boast as if you did not receive it?”

Another story about kids… One day, I was watching my 6 year old son swim at a hotel pool. He was showing off for a 4 year old girl who was there. He was bragging to her about the different sort of swimming moves he could do. Back stroke, crawl, cannonball, dive, etc. Big stuff. Well, guess what, I taught him all that. He rode on my chest and back while I swam from when he was a baby. I pushed him to learn to do all those things that he is taking credit for as he vies for this girl’s admiration. But did he think to say, My daddy taught me to swim, to go underwater, to dive, etc.? No. What he knows is that he has these abilities. Others don’t. So the difference, as far at he can tell, is between him and others who can’t swim. Is it a chore for him to swim? No - he likes it. Is it a chore for a good swimmer to help a poor swimmer? No, teaching is enjoyable, also.

People love. Even unbelievers hold love as a very important thing. We love our spouse, kids, friends, neighbors, and even enemies sometimes. But we forget that God invented love. He taught it to us; He put it in our consciences; He taught it to our parents, who taught it to us. We see that there is love in our hearts, that we want to give to family, neighbors, and maybe even enemies. But do we see that we have it because He invented it and taught it to us?

And then do we see loving strangers and enemies as a chore, or privilege? I think part of accepting our identity as a child of God is accepting that we love what He loves. He loves others. He served when He deserved to be served. So we do the same. And it is our privilege to love others - our privilege to be able to love and our privilege to desire to love.

It’s a good analogy. The nomophobes/antinomians would use language that suggests Daddy not only taught him to swim, but does all the kicking and stroking for him as well. Legalists/quasi-legalists (or just the ungrateful proud) speak/act as though they taught themselves to swim and also are personally responsible for all the metabolic processes that fuel the muscles as well as perfectly orchestrating all the neurological coordination, etc.

The truth is that we are enabled from outside ourselves, top to bottom… yet we must still do the kicking and stroking… and feeding and resitng, etc. … and, as you’ve noted, the Christian way to do it is humbly and gratefully.

(And for any who might benefit from this clarification: the ‘we’ I refer to is those already justified by faith alone and standing immutably in grace.)

Views expressed are always my own and not my employer's, my church's, my family's, my neighbors', or my pets'. The house plants have authorized me to speak for them, however, and they always agree with me.

Discussion