Jesus Teaches the Old Testament, Part 4: Midrash in the Gospels

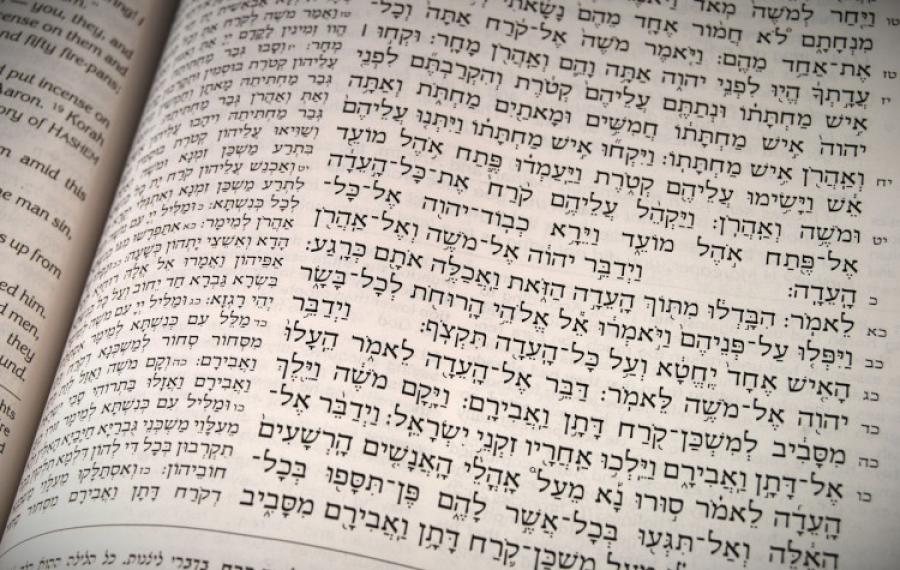

Image

Read the series.

In my previous article, I mentioned how my specific use of the term “midrash” is one possible strand of meaning for this multi-stranded term. I use the term to refer to a New Testament midrash that I consider an elaboration of an Old Testament text. That’s it. I refer to the Old Testament text as the “mother text.” The mother text plus its New Testament midrash equals a couplet.

In the world of Biblical academics, however, the term “midrash” can mean several different things. Jacob Neusner clarifies what midrash could mean:

The word “midrash” is generally used in three senses:

- It may refer to a compilation of scriptural exegeses, as in “the Midrash says,” meaning, “the document contains the following…”

- It may refer to an exegesis of Scripture, as in, “this Midrash shows us…” meaning, “this interpretation of the verse at hand indicates…”

- It may refer to a particular mode of scripture interpretation, as in the phrase, “the Jewish Midrash holds,” meaning (it is supposed) that a particular Judaic way of reading Scripture yields such-and-such results; or a particular hermeneutic identified with Judaism teaches us to read in this way rather than in some other.”1

Jesus perhaps hinted that His elaborations (midrashim) were part of His Kingdom agenda, and that his leading disciples (apostles) would continue the work. Consider Matthew 13:52:

And he said to them, “Therefore every scribe who has been trained for the kingdom of heaven is like a master of a house, who brings out of his treasure what is new and what is old.”

Scribes were, above all else, teachers and experts in the Law. Their title refers to their copy work, but they were qualified to by copyists precisely because of their academic knowledge of the Scriptures. One possible understanding of this text is that Jesus sought to train His scribes (disciples and specifically the apostles perhaps) to bring out what was old (accepted teaching from the Tanakh) and what was new (new midrash from the Tanakh applicable to the church). Bear in mind that midrash could mean something as straightforward as interpretation or application – or the exposition of what was not immediately obvious. If so, many midrashim are likely included in the New Testament documents. These midrashim, rightly recognized as Scripture, would be authoritative and inspired.

When it comes to Yeshua’s teaching, we will recognize a pattern common to rabbinic midrash. Walter Kaiser explains the origin and form of oral midrash:

The Midrashic method of exegesis had its genesis in public lectures and homilies. The lecturer would set forth the theme of his homily by reading from a passage of Scripture which enunciated the truth on which he wished to speak. He would then illustrate that truth with a parable and enforce it with a saying that was already popular with the people.2

Preaching in the “midrash style” was straightforward enough, but later Judaism evolved and split midrash into two distinct categories. One retained the name midrash (or midrashim), and implied an allegorization or less literal interpretation; the other was given the name pesha (or peshat), and suggested a normal, straightforward interpretation.

The Jewish Encyclopedia offers us the typical definition of midrash as it is commonly used today:

In contradistinction to literal interpretation, subsequently called “pesha” … the term “midrash” designates an exegesis which, going more deeply than the mere literal sense, attempts to penetrate into the spirit of the Scriptures, to examine the text from all sides, and thereby to derive interpretations which are not immediately obvious. The Talmud (Sanh. 34b) compares this kind of midshipman exposition to a hammer which awakens the slumbering sparks in the rock.3

Another Jewish source defines midrash as, “The discovery of meaning other than literal in the Bible.”4

Although the word “midrash” has evolved to refer to only the less literal interpretation of Scripture, that was not the case in the first century. As suggested above, at one time, “midrash” was a broad word and included both literal and less literal interpretations. It was not necessarily distinguished from pesha.

Longenecker comments:

Evidently, the early rabbis felt that their exegesis – whatever their methods later might be called, and however we might classify them – was a setting forth of the essential meaning of the biblical texts and therefore to be identified as either peshat or midrash, with the two terms considered to be roughly equivalent.5

As we refocus upon the Gospels, we are defining midrash by the older usage, which includes pesha. Because the Gospels record Yeshua’s oral instruction to His disciples – or to the crowds gathering to hear the Great Rabbi – we can note how His midrash was akin to that of other rabbis, and where it differs. Please bear in mind that we will elaborate later and provide adequate documentation when we do. Let’s note some associations accompanying midrash during the first century.

1. Midrash Often Included Constructing “Fences.”

The ancient Jewish rabbis who lived from about 200 B.C. to 200 A.D. are typically referred to as “sages.” One goal of these sages and latter rabbis was to set up boundaries to keep the faithful from even getting near to violating one of the 613 Torah commands that applied to them.6

Yeshua seemingly built fences within the Sermon on the Mount; He built a fence around faithfulness in marriage by encouraging his followers to nip adultery in the heart (Matthew 5:28). He constructed a fence around the commandment forbidding murder: if we refuse to harbor anger in our hearts, we are unlikely to commit murder (Matthew 5:21-22).

2. Midrash Often Made Free Use of Parables.

David Bivin writes about Jesus’ teaching style. The quotation addresses two themes: the use of parables and discipleship. We will split Bivin’s words between these two sub-headings, beginning with parables: “Parables such as Jesus used were extremely prevalent among ancient Jewish sages, and over 4,000 of them have survived in rabbinic literature…”7

Within the Talmud (a collection of ancient rabbinic writing, the earliest parts of which date back to 200 B.C.), one will find a host of parables. Some of them (which we will quote later) bear a striking resemblance to some of Jesus’ parables.

3. Midrash Involved Memorization: Memorizing a Rabbi’s Midrashim Was the First Responsibility of a Disciple.

Bivin continues:

… the rabbis of Jesus’ day spent much of their time traveling throughout the country to communicate their teachings and interpretations of Scripture. An itinerant rabbi was the norm rather than the exception. Hundreds and perhaps thousands of such rabbis circulated in the land of Israel in the first century.

To “make many disciples” was one of the three earliest sayings recorded in the Mishnah8, and perhaps the highest calling of a rabbi. Often he would select and train large numbers of disciples, but he was perfectly willing to teach as few as two or three students. It is recorded that the Apostle Paul’s teacher Gamaliel had one thousand disciples who studied with him.9

Following a rabbi meant taking leave from one’s career for weeks or sometimes months to follow the sage as he traveled the countryside. The disciple would listen as the rabbi taught the crowds who eagerly gathered to receive spiritual nurture. Perhaps a few of these disciples might one day themselves become notable sages, complete with their own band of disciples.

The disciple would memorize the teachings of his rabbi. Many devout Jews would have already memorized the Torah in their youth, so a solid Biblical background could be assumed. The disciple would listen to the casual discussions between his rabbi and fellow disciples; he might ask questions, help the sage by teaching smaller groups, and even emulate his mannerisms and habits. Rabbis would repeat their same teachings to new crowds; this would help the disciple memorize his rabbi’s words. It also explains why the Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5-7) is very similar but different in some points from the Sermon on the Plain (Luke 6:20-49).

Because the early Jewish believers were called disciples, and since a disciple’s primary responsibility was to memorize his rabbi’s teachings, there would be an abundance of information about Jesus’ life in circulation among the believing community. Some of these memorized teachings would later be included in the written gospels.

Rather than postulating a theoretical “Q” document (for which no evidence can be produced), it is much more reasonable to believe that the gospel authors availed themselves of widely memorized portions that the Gospel writers could then weave into their eye-witness accounts. The similarities between the accounts in the synoptic gospels (Matthew, Mark and Luke) can easily be accounted for in this manner. The individual authors pared down or expanded these memorized portions and chose which ones to include and which ones to exclude. After all, they were eyewitnesses or, in Luke’s case, interviewed eyewitnesses. John’s gospel, written decades later, would supplement the synoptics. Many made earlier attempts (albeit probably not quality ones) to write down these portions into accounts of Jesus’ life and teachings. Note Luke 1:1-4 and my highlighting of two words:

Inasmuch as many have undertaken to compile a narrative of the things that have been accomplished among us, just as those who from the beginning were eyewitnesses and ministers of the word have delivered them to us, it seemed good to me also, having followed all things closely for some time past, to write an orderly account for you, most excellent Theophilus, that you may have certainty concerning the things you have been taught.

We also need to remind ourselves that the Gospel “quotations” are really summaries (and brief ones at that); the use of quotation marks is a relatively modern concept. Yeshua’s words should be viewed as paraphrased summaries with some exact quotations here and there. IMO, Matthew is most likely to provide something closer to actual quotations.10

Next, we will delve into our first midrash portions as we focus upon the vital subject of discipleship.

Notes

1 Neusner, Jacob, A Midrash Reader, p. 3.

2 Walter C. Kaiser, Toward An Exegetical Theology, p. 53.

3 The Jewish Encyclopedia, article on “midrash” by Joseph Jacobs and S. Horowitz, www.jewishencyclopedia.com, accessed 02-08-23.

4 R. J. Zwi Werblowsky and Geoffrey Wigoder, editors, The Encyclopedia of Jewish Religion, p. 261.

5 Richard N. Longenecker, in Biblical Exegesis in the Apostolic Period, p. 18.

6 Since many of the 613 commands applied only to priests or were gender specific, faithful Jews would logically be most concerned about the commands that applied to they themselves.

7 Bivin, David, New Light on the Difficult Words of Jesus, p. 12.

8 The earliest portion of the Talmud, dating as far back as 200 B.C. in some instances.

9 Bivin, David, New Light on the Difficult Words of Jesus, pp. 12-14.

10 Matthew’s frequent use of Hebraisms (Hebrew idioms) like the “Kingdom of heaven” rather than the “Kingdom of God” suggest he was quoting more literally, while the others quote dynamically; the Jewish people would never pronounce God’s Name (Yahweh), but they only sparingly used His titles (like God, for instance). “Heaven” was one such substitution for “God.” This is only one of several possible examples.

Ed Vasicek Bio

Ed Vasicek was raised as a Roman Catholic but, during high school, Cicero (IL) Bible Church reached out to him, and he received Jesus Christ as his Savior by faith alone. Ed earned his BA at Moody Bible Institute and served as pastor for many years at Highland Park Church, where he is now pastor emeritus. Ed and his wife, Marylu, have two adult children. Ed has published over 1,000 columns for the opinion page of the Kokomo Tribune, published articles in Pulpit Helps magazine, and posted many papers which are available at edvasicek.com. Ed has also published the The Midrash Key and The Amazing Doctrines of Paul As Midrash: The Jewish Roots and Old Testament Sources for Paul's Teachings.

- 1187 views

Discussion