“Good and Necessary Consequences” (Part 13a)

Image

(Read the series so far.)

We all seek to apply Scripture to our lives. Those applications should be both biblical and logical. We have seen1 that at least some applications ought to be thought of as particular to each believer. This means that sometimes, at least, my application, even if it is really biblical, logical, and God-intended, is still only my application, and might not be God-intended for my friend.

But are all applications particular, or are some universal? Are there “good and necessary” applications that we all must make? And if so, what impact do these have on the matter of applications that shape and train our consciences?

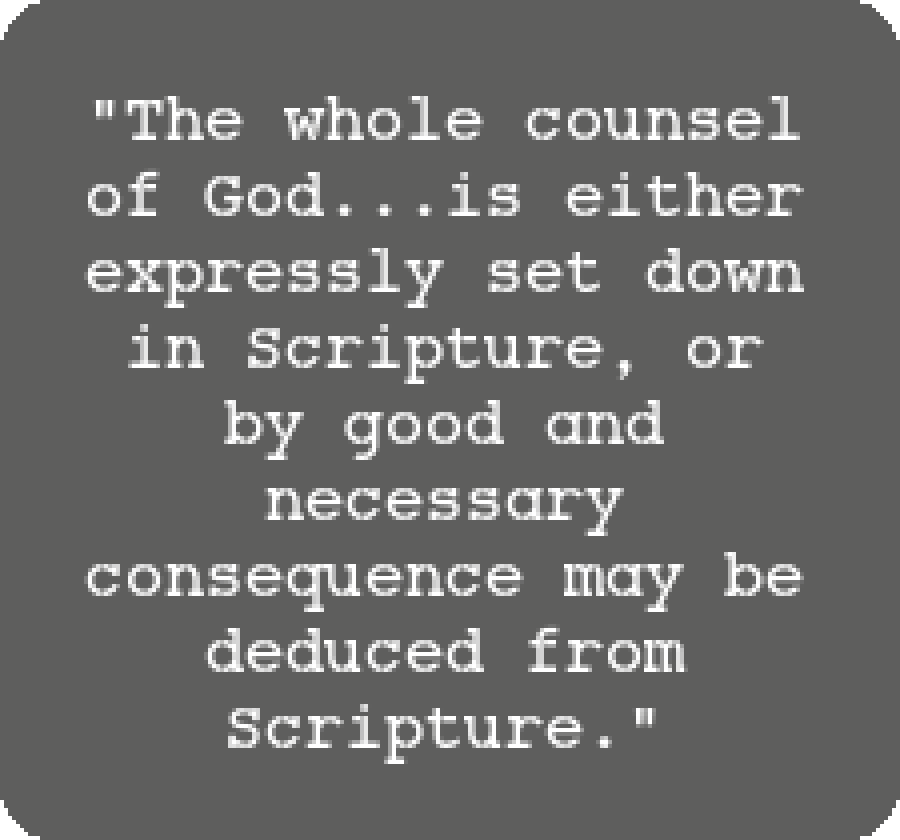

The phrase “good and necessary consequences” (hereafter, “GNC”) comes from the Westminster Confession of Faith2 (WCF):

The whole counsel of God concerning all things necessary for His own glory, man’s salvation, faith and life, is either expressly set down in Scripture, or by good and necessary consequence may be deduced from Scripture: unto which nothing at any time is to be added, whether by new revelations of the Spirit, or traditions of men.

The London Baptist Confession3 of 1689 is similar to the WCF, with its most significant variations being in the ordinances and church government. It also reads, “necessarily contained in Scripture.”4 Modern Baptists, such as Dr. Kevin Bauder, agree.5

Definition of “Good and Necessary”

James Bannerman says, “These consequences are really contained in Scripture, and therefore they are ‘good.’ They are contained, not in the words of the inspired writers, but in the relations of these words to each other.”6 The “goodness” of these consequences is a result of their being found in Scripture. Bannerman goes on to discuss:

[B]ut “necessary” as well; that is to say, one which forces itself upon any reasonable and unprejudiced mind as inevitable, plainly contained in the statements of the Word of God, not needing to be established by any remote process of refined argument.7

Ryan McGraw describes GNCs this way: “[A]s the phrase indicates, such inferences must be ‘good,’ or legitimately drawn from the text of Scripture. In addition, they must be ‘necessary,’ as opposed to imposed or arbitrary.”8

What Is the Relationship of GNC to Scripture?

In Mark 12:24, Jesus, responding to the Sadducees, insisted that they should have known that God’s statement from the burning bush proved the resurrection.9 “Jesus said to them, ‘Is this not the reason you are wrong, because you know neither the Scriptures nor the power of God?’” Jesus didn’t accuse the Sadducees of failing to reason from the Scripture, but of not knowing the Scriptures. Knowing GNC is part of understanding the Scriptures themselves.

The WCF says of Scripture and its GNC, “nothing at any time is to be added.”10 Scripture should have nothing added to it. So is a newly-reasoned GNC an addition, or not? On one hand, at the point we were given the Word, we had drawn no consequences. We’ve been adding them ever since. GNC, however, are not made, but discovered. The Trinitarian nature of God was always true and we discover its truth when we reason from the Word.

In this sense, genuine GNC are God’s Word. Bannerman said, “Whatsoever is directly deduced and delivered according to the mind and appointment of God from the Word, is the Word of God, and hath the power, authority, and efficacy of the Word accompanying it.”11 This might seem like a high claim, but note that he specifically referred to things “deduced…according to the mind and appointment of God.” Bannerman quotes Owen, “Dr. Owen, referring to an instance of this sort in Heb. i. 5, ‘that it is lawful to draw consequences from Scripture assertions; and such consequences, rightly deduced, are infallibly true, and de fide.’”12

What Is the Role of Logic in the Discovery & Authority of GNC?

GNC are proper and inevitable conclusions of the text of Scripture, and thus we are responsible for them just as we are responsible for Scripture. As we will see, the idea that these consequences are necessary doesn’t derive from the place logic holds in our thinking. It instead derives from the way Jesus and Paul used the Scripture. It is Scripture, then, that tells us logic exists and that it is a requirement for our reading the Scripture.

Ryan McGraw deals with the objection some have that “Necessary Consequences Found Faith upon Reason Instead of Scripture.”13

Forming theological conclusions does not make reason the foundation of faith and theology any more than observing and describing the natural world makes man the creator of the world… The role of reason is not to create theology from reading Scripture. Reason is a necessary tool that is used to receive the doctrines already stated and implied in the Holy Word of God. Warfield aptly noted that “if [this] plea is valid at all, it destroys at once our confidence in all doctrines, no one of which is ascertained without the aid of human logic.”14

The response is that logic is needed just to read, as Bauder explains:

When we read, we are constantly engaged in a process of drawing inferences. We observe words and phrases, and we infer that one is a subject, another is a predicate, and yet another is an object. We are constantly distinguishing nouns from verbs from modifiers from connectives. We reason that a particular sentence explains something, while another asks a question, and a third issues a command. We reason about the connection of words within a sentence, of sentences within a paragraph, and of paragraphs within a whole work.15

Is a GNC Application as Authoritative as Scripture?

With this question we are getting closer to the subject of this series. When we consider GNC doctrines, we need to apply those doctrines to our lives.

We should note that GNC language occurs in WCF, ch. 1 “Of the Holy Scripture,” and not in ch. 20, “Of Christian Liberty.” Therefore, perhaps Good and Necessary applications weren’t the intention of the Westminster Divines.

However, in ch. 1, the WCF says, “The whole counsel of God concerning all things necessary for His own glory, man’s salvation, faith and life, either expressly set down in Scripture, or by good and necessary consequence.” It could be that by “life,” the writers had in mind the application of doctrine to our lives.

Ch. 1 says of Scripture that “the true and full sense of any Scripture…is not manifold, but one.” Scripture plainly teaches that applications are manifold, with different believers applying differently. Paul acknowledged and encouraged commitment to different applications of biblical principles such as “reject idolatry,” “avoid worldly anxieties,” etc. And the OT believer applied it differently still. So perhaps we should consider applications outside of the GNC thought-system we have for Scripture.

McGraw discusses infant baptism as a GNC:

[A]lthough Baptists admit inferences and deductions with regard to the Trinity, they often rule them out as a matter of course with regard to the question of paedobaptism. Baptists often demand either one definite example of infant baptism in the New Testament or an express command to baptize children. This places an unbiblical limitation upon the discussion.16

In his defense of the practice of infant baptism, Pierre Marcel pointedly remarked, “In theology, that which follows by legitimate deductions from Scriptural norms is as exact as that which is explicitly stated…”17

There must, of course, be discussion about whether infant baptism is a doctrine or an application and, at a more basic level, about how such a distinction ought to be made.

Gillespie draws an important distinction between “necessary” and “legitimate” consequences:

Now the consequences of Scripture are likewise of two sorts, some necessary, strong, and certain, and of these I here speak in this assertion; others which are good consequences to prove a suitableness or agreeableness of this or that Scripture, though another thing may be also proved to be agreeable unto the same Scripture in the same or another place. This latter sort are in diverse things of very use. But for the present I speak of necessary consequences.18

Bannerman similarly noted the possibility of consequences being “really contained in Scripture” and yet not being “necessary”:

The consequences referred to are not only “good,” but “necessary consequences.” They might be the former without being the latter. But in order that a Scripture consequence shall come up to the definition of our Confession, it must not only be “good,”—that is to say, really contained in Scripture, really a part of Divine truth revealed there,—but “necessary” as well; that is to say, one which forces itself upon any reasonable and unprejudiced mind as inevitable, plainly contained in the statements of the Word of God, not needing to be established by any remote process of refined argument.19

McGraw discusses the difference:

Gillespie adds an important qualification at this stage of his treatment. There is a difference between legitimate consequences drawn from Scripture and necessary consequences drawn from Scripture (Gillespie, 240). This is a very important distinction. To illustrate Gillespie’s point, the duty of personal daily Bible reading is a necessary consequence drawn from those statements in Scripture that describe the godly person as meditating upon the law of God day and night (Ps. 1:2), that commend the saints for searching the Scriptures daily (Acts 17:11), and that necessitate Bible reading for faith and godliness (2 Tim. 3:16). However, how much of the Bible Christians ought to read each day, the amount of time they spend upon it, and the hour(s) of the day that they use to read the Scriptures are legitimate applications (or consequences) that admit variable expressions… If consequences drawn from Scripture are “necessary” as well as good, then they must carry the force of ‘Thus saith the Lord.’20

That distinction between “necessary” and “legitimate” consequences comes in Gillespie’s Ch. XX, which has this introduction:

That necessary consequences from the written word of God, do sufficiently and strongly prove the consequent or conclusion, if theoretical, to be a certain divine truth which ought to be believed, and if practical, to be a necessary duty, which we are obliged unto, jure Divino.21

So while Gillespie held a distinction between “necessary” and “legitimate,” he did not seem to draw such a line between the doctrinal (“theoretical”) and practical.

What Limits Should We Conceive for GNC?

Those seeking GNC can err. WCF says, “All synods or councils, since the apostles’ times, whether general or particular, may err; and many have erred. Therefore they are not to be made the rule of faith, or practice; but to be used as a help in both.”22

In 1 Corinthians 4:1-7, Paul provides a principle to be applied to teachers. They must not go, or think, beyond what is Written. For this test to be needed, the teaching must have been understood to include consequences from Scripture, some of which would be deemed “beyond” Scripture, and some of which would be “not beyond.” These latter are GNC.

In 2 Timothy 2:15, Paul admonished Timothy to “Do your best” (ESV), “study” (KJV), “be diligent” (NASB), in order “to present yourself to God as one approved, a worker who has no need to be ashamed, rightly handling the word of truth.” Paul demonstrates with this admonition that there is a possibility of wrongly handling the Word, which can lead to shame and can be averted by diligent study.

Gillespie saw these limits on GNC:

This assertion must neither be so far enlarged as to comprehend the erroneous reasonings and consequences from Scripture which this or that man, or this or that church, apprehend and believe to be strong and necessary consequences. I speak of what is, not of what is thought to be a necessary consequence, neither yet must it be so far contracted and straitened, as the Arminians would have it…23

He went on,

Let us here observe…a distinction between corrupt reason, and renewed or rectified reason…judging of divine things not by human but by divine rules & standing to scriptural principles, how opposite so ever they may be to the wisdom of the flesh. This the latter not the former reason which will be convinced and satisfied with consequences and conclusions drawn from Scripture, in things which concern the glory of God, and matters spiritual or divine.24

Here Gillespie sought to distinguish GNC from illegitimate consequences. But his method is of little use to us practically. Saying they are according to divine rather than human rules is of little benefit helping us discern them, unless he can enumerate divine rules of logic, which he makes no attempt to do.

Discussion

There are “consequences” that we ought to infer from Scripture. They are necessary. That is, we are culpable if we do not infer them. And when they are right consequences, they are authoritative. That is, to disobey them or disbelieve them is to disobey or disbelieve God.

However, they could be incorrect consequences, for even “councils may err.” Paul warned about the possibility of these errors and about the need for diligent study and holding one another to Scripture as a means of avoiding those errors. Therefore, the logical consequences we form may be “good and necessary”—in which case they are authoritative as Scripture—or they may be wrong, in which case, they have no authority.

This leaves us with significant questions about how to discern between necessary, legitimate, and illegitimate consequences. Further, what practical effect do good and necessary consequences have on our lives, as individual Christians, in church community, and in greater Christianity? Part 13b will begin to discuss these questions.

Notes

2 The humble advice of the Assembly of Divines, now by authority of Parliament sitting at Westminster, concerning a confession of faith: with the quotations and texts of Scripture annexed; presented by them lately to both Houses of Parliament by Westminster Assembly (1643-1652). Online here and here, Chapter 1, Paragraph VI.

4 (Where WCF says “good and necessary consequences.”)

5 Bauder, Kevin, Shall We Reason Together? Part Four: Ye Know Not the Scriptures, In the Nick of Time, 2006. Part 5 in his series is also important for this study. Online at SharperIron. The series came in 10 parts:

- The Challenge of Alogicality (Discussed)

- The Logic of Alogicality (Discussed)

- The God Who Reasons (Discussed)

- Ye Know Not the Scriptures (Discussed)

- Ye Ought to Be Teachers (Discussed)

- Reason and “Reason” (Discussed)

- Probability and the Limits of Logic (Discussed)

- Virtual Certainty (Discussed)

- The Problem of Premises (Discussed)

- Extra-Biblical Premises (Discussed)

6 Bannerman, James (2013-07-18). The Church of Christ (Kindle Locations 13079-13081). Titus Books.

7 Bannerman, James (2013-07-18). The Church of Christ (Kindle Locations 13089-13090). Titus Books.

8 McGraw, Ryan, By Good and Necessary Consequence, Reformation Heritage Books, Grand Rapids, MI, 2012. Kindle Location 122.

9 This passage is used in the same way by Gillespie, Robert Shaw (Exposition of the Westminster Confession of Faith, 1845), Bannerman (The Church of Christ), Bauder (In the Nick of Time), and McGraw (By Good and Necessary Consequence).

10 WCF, ch. 1, paragraph VI.

11 Bannerman, James (2013-07-18). The Church of Christ (Kindle Locations 13123-13124). Titus Books.

12 Bannerman, James (2013-07-18). The Church of Christ (Kindle Locations 13114-13116). Titus Books.

13 McGraw, Ryan (2012-12-26). By Good and Necessary Consequence (Kindle Location 936).

14 McGraw, Ryan (2012-12-26). By Good and Necessary Consequence (Kindle Locations 946-947).

16 McGraw, Ryan, By Good and Necessary Consequence, (Kindle Locations 785-787).

17 McGraw, Ryan, By Good and Necessary Consequence, (Kindle Location 807).

18 Gillespie, George, A Treatise of Miscellany Questions: Wherein Many Useful Questions and Cases of Conscience are Discussed and Resolved, University of Edinburgh, 1649, p. 240 (here in PDF, p. 269) Bannerman (Appendix

19 Bannerman, James (2013-07-18). The Church of Christ (Appendix F, Kindle Locations 13086-13090). Titus Books.

20 McGraw, Ryan, By Good and Necessary Consequence (Kindle Locations 427-436).

21 Gillespie, p. 238 (here in PDF, p. 267), emphasis mine.

22 http://www.reformed.org/documents/wcf_with_proofs/ch_XXXI.html (Ch. 31 IV) Footnote: “Eph 2:20 And are built upon the foundation of the apostles and prophets, Jesus Christ himself being the chief corner stone. Act 17:11 These were more noble than those in Thessalonica, in that they received the word with all readiness of mind, and searched the scriptures daily, whether those things were so. 1Co 2:5 That your faith should not stand in the wisdom of men, but in the power of God. 2Co 1:24 Not for that we have dominion over your faith, but are helpers of your joy: for by faith ye stand.”

23 Gillespie, p. 238 (here in PDF, p. 267)

24 Gillespie, p. 239 (here in PDF, p. 268)

Dan Miller Bio

Dan Miller is an ophthalmologist in Cedar Falls, Iowa. He is a husband, father, and part-time student.

- 157 views

Much appreciate this stud of the GNC concept.

I still struggle with how a couple pieces of this fit together… there’s a problem I can’t resolve. Here’s my quandary:

(1) A necessary inference/conclusion (in WC’s lingo, “consequence”) from Scripture has the same authority as Scripture itself.

(2) Logic being what it is, a necessary inference from a necessary inference would also have the same authority as Scripture itself.

(3) And so on… (Where does it stop? where could it possibly stop?)

(4) Further, if a necessary inference carries the same weight as Scripture, why don’t we put those inferences in writing and grow our body of infallible revelation a bit?

So the quandary is, I really can’t see any way to deny #1, but also cannot see any way to affirm 2-4! Where they necessarily lead is unacceptable. Which then leads me to question #1… and I go in circles until I shrug and give it up.

I think, on the whole, it is better to say that even necessary inferences, though binding, are of derived authority not identical authority, and that inferences from inferences must carry even less authority. Why this should be is very hard to pin down—after all, a necessary inference is forced by the premises.

… so I’m still stuck. (It reminds me of when I was a kid and decided to see if I could grasp the concept of God having no beginning and eternity having no end. The closer I got to truly apprehending, the more impossible it became… and the more my head hurt!)

Views expressed are always my own and not my employer's, my church's, my family's, my neighbors', or my pets'. The house plants have authorized me to speak for them, however, and they always agree with me.

George Gillespie (1613-1648):

A member of the Westminster Assembly, he took part in writing the Westminster Confession of Faith.

I chose him because his writing can be expected to reflect the thinking behind the words of the WCF. His work cited here, A Treatise of Miscellany Questions: Wherein Many Useful Questions and Cases of Conscience are Discussed and Resolved, University of Edinburgh, 1649, pdf, was published three years after the WCF. So there can be little doubt that his views reflect a nuanced treatment of GNC. The downside of Gillespie as a source is that it is slightly difficult reading, as you’ll see if you open the pdf.

James Bannerman (1807-1868):

Also a Scottish theologian, Bannerman’s The Church of Christ is a huge work. He’s a few generations removed from the WCF.

Ryan McGraw studied and teaches at Greenville Presbyterian Theological Seminary, which has a good reputation in our circles.

He wrote By Good and Necessary Consequence in 2012. I chose him because I wanted to read an author who is my contemporary to go along with the “dead guys” listed above.

Aaron: … (2) Logic being what it is, a necessary inference from a necessary inference would also have the same authority as Scripture itself.

(3) And so on… (Where does it stop? where could it possibly stop?)

For more reading on this sort of difficulty, see John Frame:

Discussion