Now, About Those Differences, Part Five

Read Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, and Part 4.

Read Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, and Part 4.

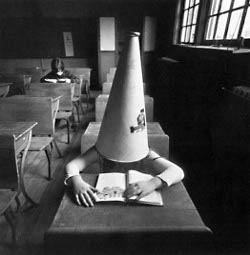

Legalism and Worldliness

Over the decades, fundamentalists and other evangelicals have played a kind of game. It is a contest of mutual recrimination. To fundamentalists, evangelicals have often said, “You are legalists.” Fundamentalists have generally replied, “You are worldly.” Both parties seem to find pleasure in this game, though neither has ever really won it.

Of course, most evangelicals are not conservative evangelicals. In common with other evangelicals, however, conservative evangelicals still tend to view fundamentalists as unnecessarily legalistic. For their part, many fundamentalists are not even willing to recognize a difference between conservative evangelicalism and other branches of non-fundamentalistic evangelicalism (usually classed under the broad label, “neo-evangelical”). These fundamentalists believe that any evangelical who is not a fundamentalist is a new evangelical and simply must be worldly.

An uninformed observer might wonder what all the fuss is about. One group observes some strictures that the other does not. Why worry about it?

The answer is that Christianity is more than a set of doctrines. Christianity is also a life lived for the love and to the glory of God. Just as some doctrinal affirmations or denials are not compatible with the gospel, so also some ways of living are not compatible with the gospel.

What follows should not be seen as any kind of “answer” to the essay by Dr. Kevin Bauder we posted here last week (what minor points I differed with him on are already expressed in the comments there).

What follows should not be seen as any kind of “answer” to the essay by Dr. Kevin Bauder we posted here last week (what minor points I differed with him on are already expressed in the comments there). Reprinted with permission from

Reprinted with permission from

Discussion