Now, About Those Differences, Part Ten

Read Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, Part 7, Part 8, and Part 9.

Read Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, Part 7, Part 8, and Part 9.

Miraculous Gifts

Are fundamentalists and conservative evangelicals really the same thing under different labels? In order to answer that question, we must investigate the apparent differences. So far in this series we have looked at two.

First, we asked the extent to which each favored dispensationalism. We discovered that fundamentalists tend to be dispensationalists while evangelicals tend to be non-dispensationalists. In evaluating the significance of this difference, however, we found that it really did not mark out a major division between fundamentalists and conservative evangelicals.

Second, we explored the accusations that (according to some evangelicals) fundamentalists tend toward legalism and (according to some fundamentalists) evangelicals tend toward worldliness. In trying to understand these mutual recriminations, we found that they tended to focus upon revivalistic taboos, concessions to the counterculture, the acceptance of extra-Scriptural second premises in moral argument, and the degree to which churches adapt their congregational life to popular culture. These differences are sometimes matters of degree, but they are nevertheless real. I am willing to argue that more often than not, fundamentalists have been more right than evangelicals on these matters, including most conservative evangelicals.

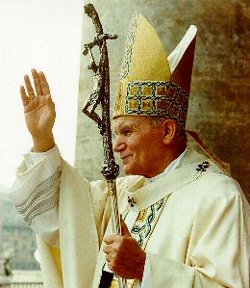

(This series on evangelical confusion about Roman Catholicism originally appeared as one article in

(This series on evangelical confusion about Roman Catholicism originally appeared as one article in  (This series on evangelical confusion about Roman Catholicism originally appeared as one article in

(This series on evangelical confusion about Roman Catholicism originally appeared as one article in  (This series on evangelical confusion about Roman Catholicism originally appeared as one article in

(This series on evangelical confusion about Roman Catholicism originally appeared as one article in

Discussion