The Kingdom of Heaven in Matthew (Part 3)

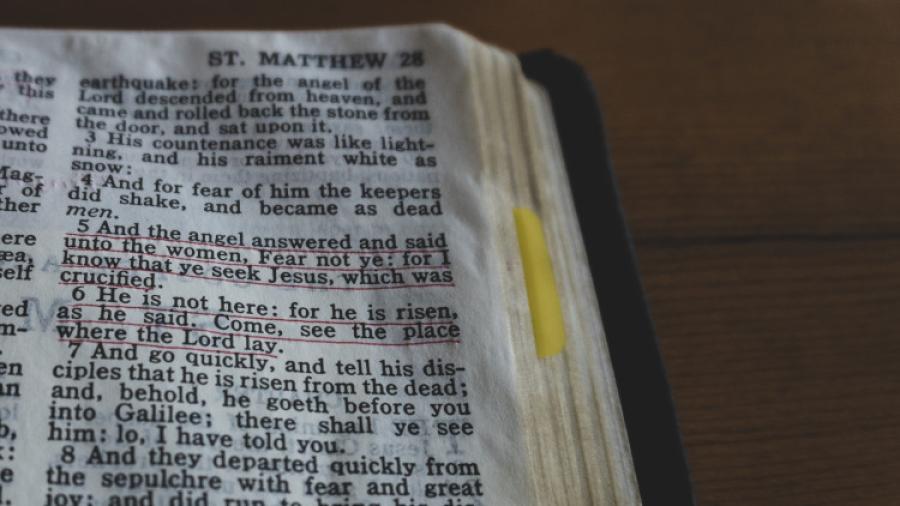

Image

This is from the first draft of my book The Words of the Covenant: New Testament Continuity. Read the series.

Interpreting Matthew 10

Jesus dispenses power to vanquish demons and sicknesses to His disciples in Matthew 10:1 in preparation for them going throughout Israel heralding the impending Kingdom of Heaven (Matt. 10:1-10). The wonders they are to perform in the sight of their countrymen demonstrate the unsuitability of putting new wine in old wineskins. The Kingdom they are preaching as “at hand” will introduce a new aeon; one that will outdo this aeon as a combine-harvester outdoes a scythe. The miracles should not be seen as only sins that attract attention, but as portents of the kind of realm the Kingdom of God will be.

But it is a striking fact that Matthew tells us that this powerful witness was to be confined.

These twelve Jesus sent out and commanded them, saying: “Do not go into the way of the Gentiles, and do not enter a city of the Samaritans. But go rather to the lost sheep of the house of Israel. And as you go, preach, saying, ‘The kingdom of heaven is at hand. Heal the sick, cleanse the lepers, raise the dead, cast out demons. Freely you have received, freely give.” (Matthew 10:5-8)

No other Gospel writer includes this saying, but Matthew felt that it was important to put it in, in all probability for contextual reasons. The road to the Gentiles could mean the actual roads to Trye and Sidon or to the Decapolis but is better interpreted as meaning any route that takes you to where Gentiles are. Carson offers a balanced explanation of the prohibition; that it would not add to the opposition they were experiencing, but that does not go far enough in my opinion. There is a focus on Israel that is legitimate, harkening all the way back to Genesis 12 and Exodus 19. It respects the covenants God made with Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob and the fact that Jesus is first the Jewish Messiah.1 His ministry was, in Paul’s later language, “to the Jew first” (Rom. 1:16; 2:10).

Then there is a section about persecution (Matt. 10:16-23). The first part of it is straightforward enough, although even there the sayings crop up in Luke and Mark in eschatological settings (Mk. 13:9–13; Lk. 21:12–17). The real difficulty enters in with Matthew 10:21-23. Verse 21 is found in Mark and Luke in proximity to “tribulation” passages (which more of later). Verse 22 includes the well-known “But he who endures to the end will be saved.” Mark 13:13 is placed right next to and looks to be consonant with the end times discourse of Jesus (which is where Matthew will also place it in unmistakable terms in Matthew 24:13-14). If one is not dead set on finding immediate first century correspondences to these sayings it begins to look as if Matthew 10:21-23 leap the centuries and land us in the days just prior to the Lord’s return in power.

This impression is only cemented by verse 23:

When they persecute you in this city, flee to another. For assuredly, I say to you, you will not have gone through the cities of Israel before the Son of Man comes. (Matthew 10:23)

Many attempts have been made to make sense of this difficult verse in a first century setting, but in my opinion they all fail. Let us pick apart the ingredients:

- The Son of Man was the one speaking to the disciples. They were not waiting for Him to come He was already there.

- Although Israel was and is a small territory, there is no evidence that Christ’s disciples covered the whole land in their evangelistic efforts.

- Soon after the death of Jesus the scattered disciples were given a wider field of evangelism and most of them, either to avoid persecution or for ministry’s sake, began to work further afield.

- If the disciples had completed their task of going through every town in Israel, they would have falsified Jesus’ words. Jesus predicted that they would not complete the task before He came.

The first and the fourth points are the most difficult to get around. To my mind the only plausible view is that the words are proleptical. The setting has shifted to the time of the end; the period running up to and including the second coming (i.e., “before the Son of Man comes”).2 This portion of the chapter might be thought about as telescoping out from post-ascension persecution (Matt. 10:16-17) to wider persecution throughout Christian history (Matt. 10:18-20), reaching into the times and events surrounding the second advent (Matt. 10:21-23). This position means the “you” in Matthew 10:23 refers to those who will be ministering for Christ prior to His return. There is nothing particularly strange about this; one finds the same thing in John 14:1-3. Whether or not one agrees with this interpretation, what cannot be escaped is that the coverage of Israel and the coming of Christ belong together.3

If Matthew 10:23b causes headaches for scholars, Matthew 11:12 comes a close second:

And from the days of John the Baptist until now the kingdom of heaven suffers violence, and the violent take it by force.

Since we are studying Jesus’ teaching on the Kingdom of God/Heaven we must tackle this verse. Once more, various attempts have been made to make sense of the passage. The attention is grabbed by the word “the violent” (biastes) who take the Kingdom by force. What kind of force can take the Kingdom of Heaven? The answer aside from the text itself is that nothing can take it, for no human violence disturbs the entrance of those whom God permits to enter, nor perturbs the Kingdom upon entering it. Bunyan famously had one of his characters in Pilgrim’s Progress cut through the swathe of guards before the king’s gate, but the exegetical basis for the image is dubious.4 One approach which I think has a lot of merit is that which looks at the verse and in particular the verbs biazetai and biastai negatively as teaching that religionists want to press into the Kingdom, and they react violently against those who are righteous. Hence, they attack the Kingdom instead of surrendering to its preconditions.5 This understanding of the verse fits well the oppositional content in Jesus’ discourse, especially Matthew 11:15-26.

As Matthew 12 begins we find Jesus answering the Pharisees regarding the matter of His disciples plucking the heads of grain to eat on the Sabbath (Matt. 12:1-8). Luke and Mark also record this encounter, but I take notice of Matthew’s report because in it he includes a statement by Jesus about Him being “greater than the temple” (Matt. 12:6). This is in addition to His claim that “the Son of Man is Lord even of the Sabbath” (Matt. 12:8).

These two statements constitute direct challenges to the Pharisees’ religion. There were scarcely any more important institutions of Pharisaic Judaism than the temple and the Sabbath (even though, much to their chagrin the temple was overseen by the Sadducees). Who was this Galilean to exalt himself above these pillars of Judaism?

Certainly, what Christ is doing here is bold, but it is not arrogant. How else is the true Son of Man of Daniel 7, the Messiah, nay, the co-Creator, going to get across to these “doctors of the Scriptures” that He transcends all those things which, in one way or another, epitomize Him? What is the Law without the covenant? What is the Sabbath without the Creator’s cessation of the first creation week? If the Christ will inaugurate the New covenant and Jesus has been announced (by John the Baptist) as He, and Jesus’ mighty miracles and impeccable character more than corroborate John’s announcement, should not the eyes and ears of all those near to God be open to His message? The question is of course rhetorical, for in God’s purposes these men and their religious neighbors (the scribes and Sadducees) would lead the opposition against Jesus. But the signs were there, and word and deed pointed the Pharisees in the right direction.

As if these already present clues were not there, Jesus quotes Hosea 6:6 to them:

But if you had known what this means, ‘I desire mercy and not sacrifice,’ you would not have condemned the guiltless. (Matthew 12:7)

On the basis of the aforementioned clues, the Pharisees should have cottoned on to who Jesus was (i.e. “God with us,” Matt. 1:23). This in turn ought to have informed their understanding of what the disciples were doing. Mercy is better than sacrificial duty, according to Yahweh, who, in His Son, is greater than the temple or the Sabbath.6 This is underlined in the very next section, where the Pharisees’ gross neglect of mercy meant they cannot stand to see a man’s withered hand restored on the Sabbath (Matt. 12:9-14).

Notes

1 See Ed Glasscock, Matthew, 222-223.

2 It is also plausible to view Matthew 10:40-42 as eschatological.

3 Some interpreters try to get round this problem by theorizing that Matthew 10:23 is based upon a non-extant source that has found its way into the text. See e.g., John Nolland, The Gospel of Matthew, 428. Carson calls the verse “the most difficult in the NT canon.” – D. A. Carson, “Matthew,” 250. He runs through seven interpretations and chooses the last, where the coming of the Son of Man refers to the coming judgment against the Jews. (Ibid, 252). But this leaves points 1 and 4 above untouched and therefore is unsatisfactory. For more analysis see Ryan E. Meyer, “The Interpretation of Matthew 10:23b.” Detroit Baptist Seminary Journal, 24.0 (NA 2019). Also, Richard L. Mayhue, “Jesus: A Preterist Or A Futurist?” Masters Seminary Journal, 14:1 (Spring 2003), 75-77.

4 John Bunyan, The Pilgrim’s Progress. See also Thomas Watson, Heaven Taken By Storm.

5 This negative take on verse 12 is favored by Craig Blomberg, Matthew, 187-188. A commentator who thinks Jesus intended a kind of double entendre is Daniel M. Doriani, Matthew, Phillipsburg, NJ: P & R Publishing, 2008, Vol. 1. 470-471.

6 This way of putting the matter owes much to the excellent comments of Robert H. Gundry, Commentary on the New Testament, Peabody, MA: Hendricksen, 2010, 49-50. Hosea 6:6 is followed by recrimination “Like men, they have transgressed the covenant…” (Hos. 6:7). Though admittedly a difficult verse, the transgression of the covenant (in all probability the Mosaic covenant) was because mercy, which reflects “the knowledge of God,” was forgotten, just as in the case of the Pharisees.

Paul Henebury Bio

Paul Martin Henebury is a native of Manchester, England and a graduate of London Theological Seminary and Tyndale Theological Seminary (MDiv, PhD). He has been a Church-planter, pastor and a professor of Systematic Theology and Apologetics. He was also editor of the Conservative Theological Journal (later Journal of Dispensational Theology). He is now the President of Telos School of Theology.

- 49 views

Discussion