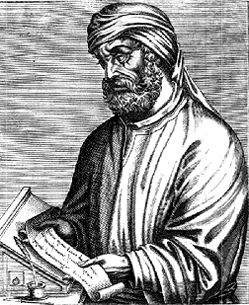

Tertullian Misses the Gospel

Tertullian was the first Latin theologian and one of the most creative minds of the second and early third centuries. In particular, his writings contributed greatly to later articulations of the Trinity. This essay focuses on the negative, but not because I think Tertullian was worthless or because I think all good Protestants should bash the Fathers to prove their orthodoxy. On the contrary, we Protestants could probably use quite a bit more familiarity with, and appreciation for, the first five centuries of Christianity. It is precisely because of how much I enjoy Tertullian that his sub-biblical gospel stings me so sharply. I’m writing this because I think we Christians could benefit from understanding how this powerful theologian and apologist came to his misunderstanding of the gospel.

Tertullian believes that there are several unforgivable sins—“murder, idolatry, fraud, apostasy, blasphemy; (and), of course, too, adultery and fornication; and if there be any other ‘violation of the temple of God’ ” (On Modesty, 19). To Protestants, this alone appears unnecessarily harsh, but Tertullian goes farther still. It is not that the Church (or at least the New Prophets, i.e., Montanists) lacks the power to forgive these sins, in Tertullian’s view; it does have the power, but it ought not forgive such sins (On Modesty, 21). Disregarding Tertullian’s scriptural arguments, which are intriguing, his practical argument is that such leniency will simply encourage more sin in the Church, which is clearly unacceptable. There are a few hints that perhaps God in His mercy will forgive the repentant, but in any case, they cannot be returned to the fellowship of the Church.

What a twisted view of the gospel! Yet, it is more profitable to explain the context of this error than simply to decry it. We must start with Tertullian’s view of the Church. He is a perfectionist, or very nearly so. The Church is the bride of Christ, so no spot or blemish should be allowed in it. Anyone who could be condemned by the outside world on moral grounds should have already been cast out of the assembly (Apology, 44). Tertullian’s apologetic strategy both presupposes and necessitates this perfectionist tendency. Tertullian’s main argument for Christianity is the moral blamelessness of Christians. According to Tertullian, Christians simply don’t engage in bad behavior, at least nothing too bad. Although he does grant that Christians may need one (and only one) dose of post-baptismal forgiveness for some non-mortal sin (On Repentance, 7), Tertullian does not paint a picture of Christians struggling against sin, except in an unending stream of victories.

Discussion