"Replacement Theology" - Is It Wrong to Use the Term? (Part 1)

Image

Recently I have been reminded of the Reformed community’s aversion to the label of supercessionism, or worse, replacement theology. In the last decade or so particularly I have read repeated disavowals of this term from covenant theologians. Not wanting to misrepresent or smear brethren with whom I disagree, I have to say that I struggle a bit with these protests.

“We are not replacement theologians” we are told, “but rather we believe in transformation or expansion.” By some of the objectors we are told that the church does not replace Israel because it actually is Israel — well, “true Israel” — the two designations are really one. This move is legitimate, they say, because the “true Israel” or “new Israel” is in direct continuity with Israel in the Old Testament.

In this series of posts I want to investigate the question of whether it is right; if I am right, to brand this outlook as replacement theology and supercessionism.

Basics: What Is a “Replacement”?

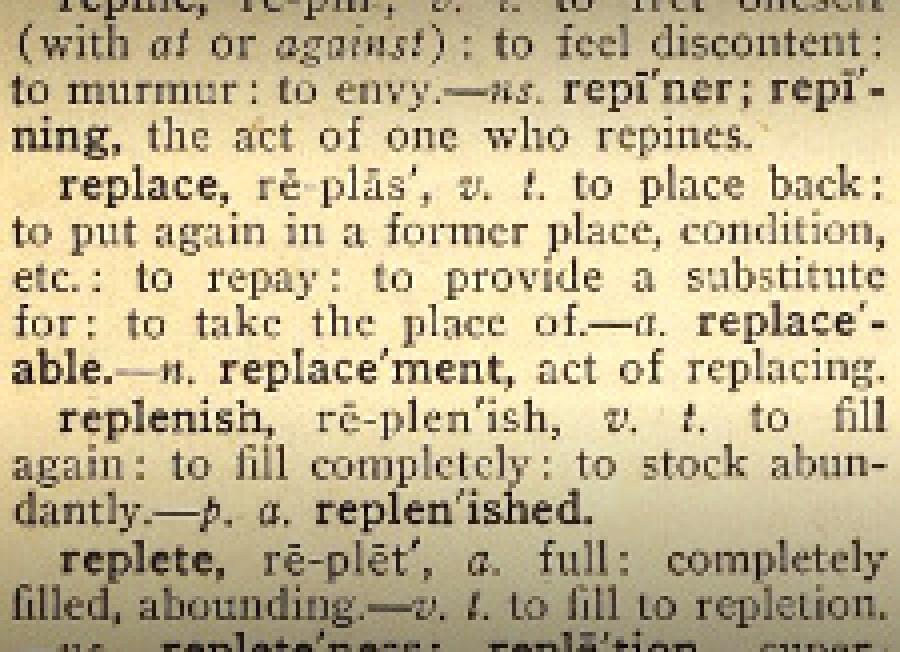

A good thing to do as we begin is to have a definition of the word at issue. Websters New World Dictionary defines the word “replacement” thus:

1. a replacing or being replaced 2. a person or thing that takes the place of another…”

The entry for “replace” says,

1. to place again; to put back in a former or the proper place or position. [obviously, this does not apply to our question.]

2. to take the place of… 3. to provide a substitute or equivalent for.

The synonym “supersede” means that something is replaced by something else that is superior. In the way I use the terms in a theological context I mean “to take the place of.” The third meaning (i.e. to substitute) is somewhat relevant since some may be claiming that OT Israel has been switched out for another Israel. By “supercessionism” then, I mean any theology that teaches a switching out of “old Israel” with “new,” “true Israel.”

The question before us is whether the Church takes the place of Israel in covenant theology, and if so how? To answer that question we must ask several more. These include such important questions as, ‘what exactly do covenant theologians say about the matter? And do they ever use replacement terminology themselves?’; ‘Can their understandings of Israel and the church, and so their “expansion” language, be supported from the Bible?’

If “Israel” and “the church” are the same thing then clearly we have our answer, and I can stop writing. If the church and Israel are the same any question of replacing one with the other starts and stops with the simple swapping of names.

Identifying “Israel”

In the Old Testament Israel is either a person, the man Jacob who was renamed “Israel” by God in Genesis 32:28, or the nation of people (sometimes a part of them either in rebellion or redeemed) who stem from Jacob who are called “the children of Israel” in Genesis 32:32 (Israelites), or a designation for the promised land (cf. Josh. 11:16, 21).

Covenant theology adds to these designations another. For example, an anonymous devotional at Ligonier’s website entitled “Who is Israel?” claims that,

Finally, the term Israel can also designate all of those who believe in Jesus, including both ethnic Jews and ethnic Gentiles. In Galatians 6:16, the Apostle applies the name Israel to the entire believing community—the invisible church—that follows Christ. Paul does not make this application specifically in Romans 11; however, this meaning is clearly implied in his teaching about the one olive tree with both Jewish and Gentile branches (vv. 11-24).

Although nowhere does the New Testament explicitly equate Israel with the church, the assumptions that lead the writer to his conclusion (not to mention his exegesis of Gal. 6:16 and his use of the Olive Tree metaphor) come into focus once his view of the church is understood.

Chapter Twenty-five of the Westminster Confession of Faith defines the Church like this:

I. The catholic or universal Church, which is invisible, consists of the whole number of the elect, that have been, are, or shall be gathered into one, under Christ the Head thereof; and is the spouse, the body, the fulness of Him that fills all in all.

II. The visible Church, which is also catholic or universal under the Gospel (not confined to one nation, as before under the law), consists of all those throughout the world that profess the true religion; and of their children: and is the kingdom of the Lord Jesus Christ,the house and family of God, out of which there is no ordinary possibility of salvation.

You will notice that this definition places every saved {elect} person in human history into the Church. It also places all the those elect who will be saved into the Church. The Church is also seen as the Body of Christ, as well as “the kingdom of the Lord Jesus Christ, the house and family of God” outside of which there is no salvation.

Acceptance of this definition pretty much wraps things up as far as OT Israel is concerned. The saved saints under the Mosaic covenant were simply the Church of the time. Also, the kingdom which was repeatedly promised to the remnant of Israel is, well, the Church. Not the land, not Jerusalem, not the national throne or the temple on Mt. Zion, just the Church.

There is reason to dissent from the honored position of the Puritans cited above, and I shall have to do so later on. But right here my intention is simply note that according to this way of thinking the elect Church and elect Israel are the same thing. If this is the right tack then there is nothing wrong with the following thought from Anglican theologian Gerald Bray:

As men and women who have been grafted into the nation of Israel by the coming of Jesus Christ, Christians…lay claim to [the] love and the promises that go with it. – God Has Spoken, 41

Very well, we are to believe that Christians have been grafted into Israel. Bray too is alluding to Paul’s metaphor of the Olive Tree in Romans 11. Again, “Israel” here must mean believers, therefore, all believers are “Israel.” That is, IF these claims are true.

(To be continued…)

- 202 views

Ethnicity and genealogy meant nothing apart from faith in the OT.

I wouldn’t agree with that at all. The NT seems to undermine this fairly clearly by its emphasis on the inclusion of the Gentiles. The reason that was hard for Jews is because ethnicity and genealogy did mean something in the OT. It wasn’t everything, but it was something major. Even unbelievers were included in the covenant blessings on the nation. The change to that in the NT was troubling to them and hard to accept because of what the OT taught.

The NT makes it clear that promises were fulfilled in the quintessential only obedient Israelite who is the final sacrifice, the Temple, the inaugurator of the one New Covenant, etc.

I wouldn’t agree with that either. The NT appeals so the OT too many times in too many specific ways for this to stand. I think this can only stand if we seriously minimize the OT teaching and the NT use of the OT.

The Church is the chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, a people for his possession. OT language for NT believers. Those OT descriptors describe the Church where there are both Jews and Gentiles and in which there is neither Jew not Gentile.

Using the same descriptors doesn’t mean it is the same group, or that the promises given to one of them transfer to the other.

I know you are writing briefly, as am I, and neither is taking the time to unfold everything. But I am also confident that you know that this is not a good response to the issues I addressed. Dispensationalists have long since addressed these issues and I don’t think it is complicated. I think the alternative complicates matters more because it requires us to essentially ignore what the text says.

When I began to understand how NT authors interpreted the OT, I was compelled to revisit my OT interpretation in the light of NT revelation. I am convinced that NT revelation must clarify the way we understand the OT.

Which leads to this question: If you realized you couldn’t interpret the OT without the NT, why are you so sure you are interpreting the NT correctly?

It seems to me that the OT had to have meaning in and of itself. Those people in the OT were held accountable to the OT revelation without the NT clarification. Your hermeneutic seems to undermine that since it essentially argues that we cannot properly interpret the OT without the NT. Yet the OT people were punished or blessed based on that revelation alone without the NT.

Is the NT superior revelation, or not? I don’t have time just now to look up texts, but several NT statements indicate that it is. The way NT authors interpreted the OT is definitive. Their understanding is perfect, ours is not. How do I know that my NT interpretation is correct? I don’t, though I believe it is closer to correct than those who squeeze the NT to fit a previously locked in OT interpretations. However, I, like all God’s people, have imperfect understanding, and must continue to study and endeavor to arrive at the true meaning of Scripture.

It goes without saying that OT saints also wrestled with questions and partial obscurity, which the NT helps to clarify. Total clarify will not come in this life. I cannot accept the premise that God will not hold us responsible for partial revelation unless we have total understanding of all revelation.

G. N. Barkman

Thank you for the pushback. I don’t think we’re looking for agreement so it’s good to discuss these issues.

Ethnicity and genealogy - the OT promises given to ethnic Jews are of little or no account without faith. There is so much in the NT that sheds light on the OT and the NT teaching becomes definitive (in agreement with G. N. Barkman). According to Jesus unbelieving Jews of his day were offspring of Abraham but not Abraham’s children (John 8); the sons of the kingdom will be thrown into outer darkness (Matt. 8). Jesus has spoken. So yes what Jesus (and the apostles) says takes precedence over how old covenant people understood or misunderstood what was spoken and written. No surprise, Even the prophets didn’t always understand. What counts in the era inaugurated by Jesus is being in him, not flesh and blood. In Christ we don’t lose our ethnicity but it doesn’t count for anything.

As for the descriptors you either have one group or two. Of course if someone believes there’s two peoples of God, Israel and the Church then sure the descriptors can apply to both. I believe the Scripture teaches the unity of God’s people. The wall has come down making “both one,” “one new man,” both have access in one Spirit, etc, etc. Like GNB I read Scripture through a dispensational hermeneutic for years and made things fit. I can still argue that way because I think I see the logic of it once one begins going down that trail. I just can’t defend it anymore. I don’t need to change anyone’s mind.

G. N. says, “What makes it clear is the theological interpretation which Steve is employing.” And what makes it obscure is the theological interpretation that Paul is employing.”

If what he says is correct then ALL interpretation is theological interpretation and all those new books on the theological interpretation of Scripture as a viable hermeneutic are pointless. Now I think the reason that G.N. finds my interpretation “obscure” is that he believes that the OT cannot be understood without the NT. Of course, that stance automatically makes the OT obscure and makes a nonsense of the doctrine of the clarity of the OT. The reason CT’s do this is because they believe, sincerely, that the writers of the NT reinterpret the OT. What they do not see is that the reinterpretation (they may adopt a softer term) is done, not by the Apostolic authors, who can be understood very well in hermeneutical continuity with the OT, but by them. It is their interpretation of the NT that drives things.

A second point may be made from another of G.N.’s remarks:

“Is the NT superior revelation, or not? I don’t have time just now to look up texts, but several NT statements indicate that it is.”

If it is then we have primary and secondary scriptural revelation, i.e. the NT is “superior” to the OT in what way? We certainly have two levels of perspicuity.

I respect the fact that G.N. doesn’t have time to provide the requisite texts to prove his thesis. But I think he ought to take some time to do it. Even though he has taken the thread down this (important) road, I want to put a reminder in here that this is not the subject of the article. Perhaps after Parts 2 & 3 this matter will be clearer?

Is the NT superior revelation to the OT? In a word, No.

Dr. Paul Henebury

I am Founder of Telos Ministries, and Senior Pastor at Agape Bible Church in N. Ca.

Steve said,

Like GNB I read Scripture through a dispensational hermeneutic for years and made things fit. I can still argue that way because I think I see the logic of it once one begins going down that trail. I just can’t defend it anymore. I don’t need to change anyone’s mind.

He’s quite right. I respect that.

Dr. Paul Henebury

I am Founder of Telos Ministries, and Senior Pastor at Agape Bible Church in N. Ca.

This is a good series. I hope Steve and GNB will stick around for the rest of it. It will be fun. I’m just waiting for Bro. Henebury to publish his book on Christ as the center! :)

Tyler is a pastor in Olympia, WA and works in State government.

Is the NT superior revelation, or not?

I can’t imagine saying that one part of the Bible is superior revelation to another part as if part of God’s revelation can be relegated to an inferior status. But I think you have tapped into a common problem—that people denigrate (uintentionally) one part of God’s revelation in favor of another part. I don’t think there is any merit for that, at least that I can find.

The way NT authors interpreted the OT is definitive. Their understanding is perfect, ours is not.

Let’s assume this is true. (I think it is true though it needs more explication.) You are interpreting their interpretation. And you have acknowledged that you don’t know your interpretation is correct. So you are really no better off, are you? Which leads back to my original question: Why do you trust your interpretation of the NT more than your interpretation of the OT?

I think it is more complex.

I don’t, though I believe it is closer to correct than those who squeeze the NT to fit a previously locked in OT interpretations.

Here I am not sure how to respond because I don’t know what “previously locked in OT interpretations” means. As a dispensationalist, I feel no need to “squeeze the NT to fit a previously locked in OT interpretations.”

Let me ask you a series of questions and see if perhaps I can make some headway in understanding your position (or whoever will answer):

Were OT saints held accountable to believe and obey the OT revelation without benefit of the NT revelation? (If not, then I think the discussion is over and any talk of a coherent bibliology or revelation is finished.)

If so, was God holding them accountable to something false or something true? If false, then why are they held accountable to believe and obey something false? If true, then isn’t the OT sufficient for true belief in that era? And if true, in what sense can that change without them having been called to believe something false at least for a time?

It goes without saying that OT saints also wrestled with questions and partial obscurity, which the NT helps to clarify.

But the question is how does it clarify? Does it clarify by adding new unknown revelation? By extending previous revelation? By changing previous revelation?

I think it is true that the NT can bring additional revelation that was previously unknown (such as the church) or add information to previous revelation (such as a fuller understanding of the Messiah’s mission). But that can’t change the OT revelation to be something it wasn’t.

I cannot accept the premise that God will not hold us responsible for partial revelation unless we have total understanding of all revelation.

This is exactly what I would say. And the OT saints were held accountable to believe and obey the partial revelation, even as we are.

[Paul Henebury]Steve said,

Like GNB I read Scripture through a dispensational hermeneutic for years and made things fit. I can still argue that way because I think I see the logic of it once one begins going down that trail. I just can’t defend it anymore. I don’t need to change anyone’s mind.

He’s quite right. I respect that.

Still part two and part three :-)

Larry, Are you saying that OT Saints could not be held responsible for partial revelation unless they could clearly understand it all? But the NT makes obvious that most first century Jews did not understand the prophecies about Christ very well, if at all. Were they, therefore, not held responsible? Or, perhaps you are saying that God could not hold them ressponsable unless the OT Scriptures were capable of being correctly understood. But its one thing to say they could be correctly understood, and another to assert that you, or I, or anyone else, does in fact understand them correctly.

If I have an understanding of the OT that clashes with a declared understand of Christ or the Apostles in the New Testament, then I must yield my understanding to theirs. New Testament Scripture trumps OT interpretation. That’s what I am trying to say.

Paul, I retract my statement that NT Scriptures are superior to the OT. What I meant to say is that my interpretation of the OT is trumped by the inspired interpretation of the New Testament. My previous statement was incorrect because it was imprecise, but perhaps this will help.

G. N. Barkman

Appreciate the way you have re-expressed what you meant. Thank you. I too (like Larry) believe that the NT furthers the revelation of the OT. Our differences stem from our interpretation of the NT.

Dr. Paul Henebury

I am Founder of Telos Ministries, and Senior Pastor at Agape Bible Church in N. Ca.

Are you saying that OT Saints could not be held responsible for partial revelation unless they could clearly understand it all?

I am actually saying quite the opposite, that they were responsible for it even if they didn’t understand it fully. It was clear enough for them to understand and be held responsible without the NT. To me, that flies in the face of those who say that the NT is necessary to understand the OT. I don’t see how that can be sustained. Jesus condemned the Pharisees and even a couple of followers for not believing the OT on its own merits.

But the NT makes obvious that most first century Jews did not understand the prophecies about Christ very well, if at all. Were they, therefore, not held responsible?

Somewhat true. There was enough revelation to believe and they are judged for not believing it (e.g., John 5, Luke 24). Jesus called them foolish and slow because they refused to accept the OT on its own.

If I have an understanding of the OT that clashes with a declared understand of Christ or the Apostles in the New Testament, then I must yield my understanding to theirs. New Testament Scripture trumps OT interpretation. That’s what I am trying to say.

I can agree with that. But that assumes that you have properly understood the NT. And that assumes that we can do what they did. I am persuaded that Longenecker was onto something in his article on “Can We Reproduce the Exegesis of the New Testament?” (and an article by John Walton in TMSJ). In essence, the answer is no. They were operating under inspiration. We are not. Much of their use of the OT does not seem to be historical grammatical exegesis. And therefore, it can’t be replicated by non-inspired people.

So when we come to a place where the NT does not interpret the OT we are back to exegesis. And that must assume that the OT is intelligible and coherent on its own merits, even if not complete for us.

So the NT furthers the OT and adds additional revelation that the OT doesn’t have. and doesn’t add to or clarify some revelation the OT does have. But it doesn’t contradict or change the OT.

Exactly. Their inspired interpretations of OT prophecies do not conform to most DT interpretations. Therefore we should examine their interpretations carefully to: 1) learn what the OT passages that they interpreted actually mean, and 2) allow them to guide us in the proper way to interpret other OT passages.

Dismissing their conclusions because we are not inspired misses the point It is precisely because they were inspired that we must give greater weight to their conclusions than to the exegesis of uninspired commentators.

G. N. Barkman

Their inspired interpretations of OT prophecies do not conform to most DT interpretations.

I am not sure I would grant this at all. What passages do you have in mind?

Remember, the NT use of the OT is multi-faceted. There are more than dozen ways that the NT uses the OT from simply borrowing words to direct fulfillment identification and a whole lot in between. And frankly, we don’t always know what they are doing or how they are doing it. Sometimes the NT doesn’t give an interpretation at all.

Therefore we should examine their interpretations carefully to: 1) learn what the OT passages that they interpreted actually mean, and 2) allow them to guide us in the proper way to interpret other OT passages.

You sound like Dennis Johnson or Pete Enns here (among others). I think it is flawed in a number of ways. I think Kaiser’s response to Enns in the Three Views book was pretty devastationg.

With respect to #1, the NT use may not be a guide because it doesn’t give a meaning in some cases. Again there are a number of different ways and not all of them give the OT meaning. So the NT doesn’t always tells us what the OT passage meant in its context.

With respect to #2, remember that much of the OT isn’t even addressed by the NT so there is no guide for that. I think you are underemphasizing the fact of inspiration. We are not inspired and therefore we cannot replicate what they did in some cases. We don’t even know what they did so how can we imitate what we don’t even identify?

Walton rightly say, :The credibility of any interpretation is based on the verifiability of either one’s inspiration or one’s hermeneutics” (Walton 2002, 70). IF you don’t have inspiration, then you have only exegesis (or imagination/making it up). The burden of preaching is to show that the text says what we are saying. The only way to do that is through exegesis of the text.

Dismissing their conclusions because we are not inspired misses the point It is precisely because they were inspired that we must give greater weight to their conclusions than to the exegesis of uninspired commentators.

I agree absolutely but this is simplistic. We must not dismiss their conclusions. But what about the times when they don’t give an interpretation? Or again, when they don’t even address a text. And what about the complexities? Scholars today, to say nothing of pastors, don’t agree on how the NT uses the OT in particular cases.

It seems to me, at the end of the day, we have the text in front of us and God has called us not to give our imaginative thoughts on it but rather to say what the text says, to “preach the word.” Preaching the word requires exegeting the text in its immediate context and its canonical context. But the text has to rule. If at the end of the sermon, the audience cannot clearly see the conclusion in the text, I think we have not done our job.

If we will start with the OT Scriptures cited in the NT and accept their inspired interpretation, we have a good foundation to better understand for those more numerous Scriptures of which the NT writers say nothing. Let’s not jump to the un-addressed passages until we have given due consideration to those which are addressed.

I will give two example in general terms, since I am facing a deadline and do not have time to look these up. Example # 1. The NT declares repeatedly that John the Baptist is the Elijah foretold in the OT. In other words, the Elijah who is to come was not the literal OT prophet, but rather one who would come in the power and spirit of Elijah. Reading ony the OT text in Malachi, I doubt that i would have understood that prophecy correctly. Reading the words of Christ I now can.

Example # 2. Jeremiah foretold a new covenant to be made with the house of Judah and Israel. The book of Hebrews identifies this with the New Covenant inaugurated by Christ which embraces the church. Conclusion: the church fulfills the prophesy made to Judah and Israel and in fact is the Israel and Judah of which the OT prophet speaks.

I have read DT explanations which deny these conclusions. I find them unconvincing. They seem strained, as if to protect DT at the expense of NT illumination. IOW, these statements can be and are of necessity explained away, but explained away is not the same as correctly explained. If historical grammatical exegesis is applied to these NT texts, a less than strictly literal interpretation of the OT texts emerges. If strictly literal exegesis is utilized with the OT texts, something less than plainly literal is imposed upon the NT explanations of these texts. Either way, some strictly literal interpretation must give way. With DT, the NT is always required to give way to the OT. I find that odd. I am more convinced by the approach that takes a straight-forward understanding of the NT, and re-interprets the OT in the light of the inspired NT interpretation.

G. N. Barkman

Discussion