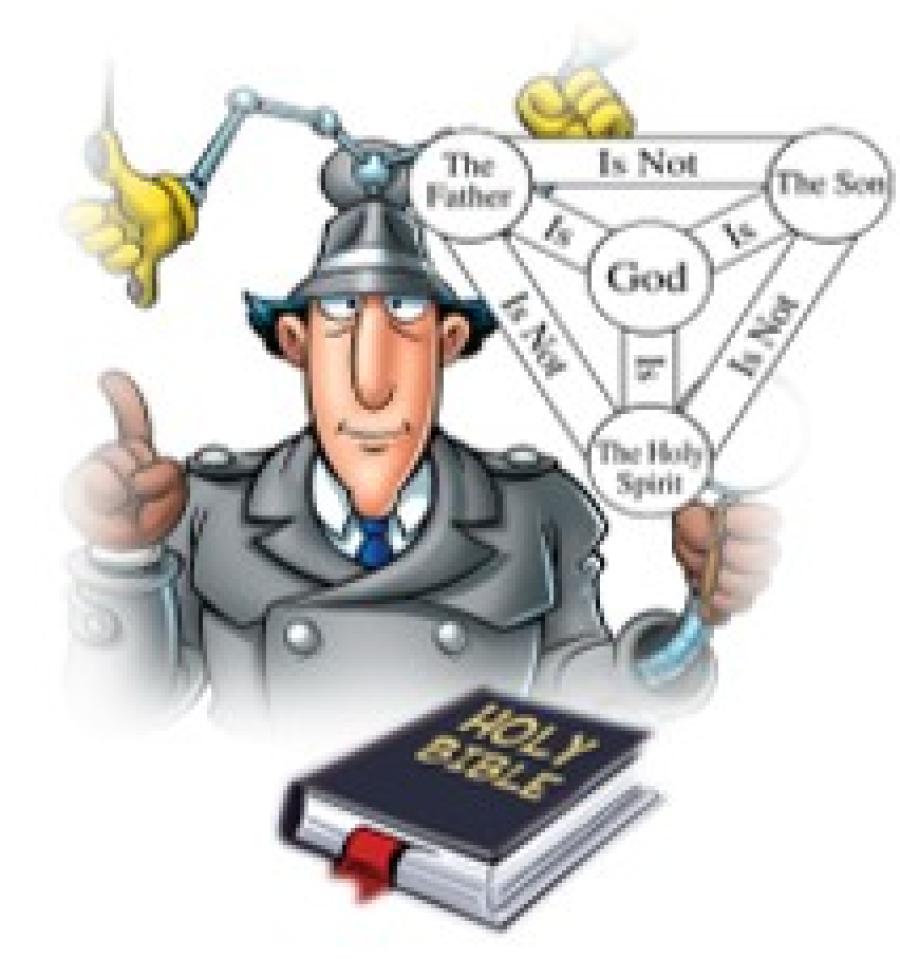

Inspector Gadget and the Trinity - Bible Study as Detective Work

Image

In the local church, the Trinity is usually expressed as an established truth; a fact. It’s often accompanied by a nice summary statement and some key verses. In a seminary context, the student (let’s call him Biff!) will be forced to go a bit deeper than that.

In theology proper, Biff will be introduced to the doctrine itself. In christology, Biff will study the virgin conception, the kenosis, and the ascension. If Biff is compelled to take historical theology, he’ll learn all about the Christological heresies of the early centuries. If he goes to a serious seminary, he might even be forced to present a biblical theology of the Trinity during a systematic theology class. Then, he graduates and is off to a local church—ready to conquer the world!

However, we live in the real world. In this world, it’s entirely possible Biff didn’t pay attention during theology proper. Maybe he sleepwalked his way through his term paper that semester. Maybe he went through seminary without ever even studying the doctrine for himself. Perhaps Biff took his required two years of Greek, then sold his battered copy of Mounce on Amazon and donated his tattered edition of Young’s intermediate grammar to Goodwill. He still has Wallace’s tome, but it’s in a box somewhere in the basement … with the spiders. Biff hates spiders, so Wallace stays in his box.

Biff doesn’t have the capability to interact with Jehovah Witness literature about the absence of the article before θεὸς in John 1:1. He doesn’t know who Colwell was, and he certainly isn’t interested in his “rule.”1 Pastor Biff cannot appreciate how significant the title κύριος is when it is applied to Jesus Christ, because he has never looked at the Septuagint … because he hates Greek. He used his old Greek flashcards as kindling for the youth group bonfire this summer. Everybody ἠγάπησαν the s’mores!

The result is that Biff believes the Trinity, but he doesn’t know why. He knows he’s supposed to believe the doctrine, so he does. Simple! His standard proof text is 1 John 5:7-8, along with Genesis 1:26. He faithfully preaches the Trinity at the appropriate times, and even throws in a three-leaf clover illustration every once and a while, for good measure. Pastor Biff doesn’t realize it, but he’s actually a modalist. His congregation is even worse.

Biff’s problem is a symptom of a larger issue; Christians often believe doctrines simply because they know they “should.” Many believers are orthodox because of convenience, not conviction. This is a pitiful state of affairs. The doctrine of the Trinity goes right to the heart of who God is. We must know this doctrine, understand it as best we can from the pages of the inspired and inerrant Scripture, and believe it because we know it’s the truth. That’s where Inspector Gadget comes in. But first, a brief definition!

Definition of the Trinity

James White provided the best and most helpful definition of the Trinity I’ve found:

Within the one Being that is God, there exists eternally three co-equal and co-eternal persons, namely, the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit 2

This definition is excellent, because it captures five key things about the doctrine of the Trinity which every Christian needs to understand.3 Each of these facts are always true. In fact, this definition and the five implications should be memorized by every Christian:

- Each Person is fully and completely divine4

- Each Person has always been co-equal,5

- Each Person has been around forever,6

- Each Person is, in some way, distinct from the others, and yet

- Each Person is, in some way, one with the others7

This definition is not found, verbatim, anywhere in the entire Bible. The clearest single passage in the KJV which supports the Trinity (1 Jn 5:7b-8a) is likely not original at all.8 Much more could be said about the Trinity. I could begin quoting systematic theology texts. I could dive into historical theology. I could cite Tertullian. I could trot out some valuable church creeds (the Athanasian Creed is especially helpful). I could direct you to Tim Challies’ extraordinarily helpful infographic about the Trinity, which, by the way, is a very good poster to hang on the wall at your church for members of the congregation to gawk at (the kids especially like it). But, I don’t want to do that. In technical terms, I’m going to present a biblical theology of Jesus Christ and the Trinity from the Gospel of Mark. In real language, we’re going to do a Bible study. We’re going to take an orthodox statement of Trinitarian doctrine and put it to the test through an entire book of the Bible. It should be a real hoot.

Inspector Gadget & the Trinity

I was on active-duty with the U.S. Naval Security Forces for 10 years. I was a criminal investigator at two different duty stations. I’m a Maranatha Baptist Seminary graduate, a Pastor, and now a senior insurance fraud investigator with the State of Washington. I’m used to detective work. When you get a criminal complaint, your job is to gather the facts, lay them out, and accurately interpret them. Did an offense actually happen? What offense was it? In light of the facts, can I demonstrate the suspect’s actions meet the legal criteria of that crime? Can I prove it? Bible study is the same way.

Christian doctrine about the Trinity was formulated by meticulously piecing together everything the Bible says about our One God, and the Divine People of Father, Son and Holy Spirit. Christian doctrine, properly done, is the result of pure detective work. Your only infallible authority is the Word of God; not commentaries, not books, not Pastor Google, not favorite preachers, and not (heaven forbid!) internet chat forums. Gather the Biblical evidence, lay it all out, and interpret it—what do the facts tell you? This is why Inspector Gadget is important. He’s a detective. He’s “always on duty!” Yes, he is incompetent—but we can do better. This is how you study out a doctrine for yourself, and do Biblical detective work:

- You survey everything Scripture has to say about a particular issue. For example, the intention of Christ’s atonement, what the Gospel is and isn’t, what baptism really means, etc.

- This can be an overwhelming task, so you usually start with a small slice of Scripture (e.g. the Gospel of Mark)

- You lay out all the data and take a fair and honest look at it. You ignore what you want to see, and deal with what you actually see. Our preconceived notions and ideas are always subject to the Bible, not the other way around

- Based on the Biblical data you’ve gathered, you pull together some conclusions and make a summary statement. This is systematic theology, a systemized presentation of doctrine based on an honest and thorough study of the text

- You expand your scope of inquiry to different texts (e.g. the General Letters), gather even more evidence, and re-evaluate your summary conclusions as necessary

That is how you study a subject in the Bible fairly and honestly. You systematically comb through the Scriptures. You do it line by line, chapter by chapter, book by book, testament by testament. You gather data, you fairly and accurately interpret that data, and only then can you come to conclusions. This is detective work. It’s the most rewarding thing in the world to know, in your own heart and soul, that you’ve studied a Bible doctrine and you’re convinced of it in your own mind for a real reason. You shouldn’t plan to stand before Jesus one day and stammer, “But, Pastor Biff said! …”

This series will be a Bible study on the Trinity. This is obviously a massive subject, so we’re going to take some realistic steps to narrow down our focus. We’re only going to look at Jesus Christ, and we’re only going to look at the Gospel of Mark. This will be a long series, and no doubt some people will tune out or lose interest along the way. But, no matter how much (or how little!) time somebody spends in studying the Trinity, any investment of effort and energy on this topic is certainly time worth spending.

Notes

1 See Daniel B. Wallace, Greek Grammar Beyond the Basics: An Exegetical Syntax of the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1996), 256-263, 266-270 for a long discussion of Colwell’s Rule and John 1:1.

2 This definition is from James White, The Forgotten Trinity (Minneapolis, MN: Bethany House, 1998), 26.

3 Whenever the doctrine of the Trinity comes up, Bible students are almost always compelled to issue about 500 caveats and 250 clarifications about what they are and are not saying, and agonize with blood, toil, tears and sweat over every word to ensure they are not taken out of context. I won’t bother to do that. This series began as a series of Wednesday evening Bible studies at my church when I was a Pastor. I intended it to accurately communicate weighty, orthodox doctrine in a user-friendly way to ordinary people. That is still my goal with this format.

4 Athanasian Creed, clause 15.

5 Ibid, clause 26.

6 Ibid, clauses 8, 21-23.

7 Ibid, clauses 3-6.

8 There are no Greek manuscripts with this reading until 1400 years after Christ—and even then, there are only four! There are four others which date from the 10th century onwards, but in those manuscripts this reading is only scribbled in the margins, not in the text itself. During the all the disputes against all the Christ-denying heretics during the first five centuries of the Christian church, no Christian ever used that verse in all the writings of theirs we possess—and we possess a whole lot of them (e.g. Ante-Nicene Fathers series).

If you have a UBS-5 or an NA-28, you can see all this from the critical apparatus. See also the discussion in Bruce Metzger and Bart Ehrman, The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration, 4th ed. (New York, NY: Oxford, 2005), 146-148. It is telling that Maurice Robinson and William Pierpont also omitted 1 Jn 5:7b-8a in their edition of the Byzantine Text.

For a brief defense of this passage as belonging to Scripture, see Thou Shalt Keep Them: A Biblical Theology of the Perfect Preservation of Scripture, ed. Kent Brandenburg (El Sobrante, CA: Pillar & Ground, 2007), 173-175. For one of the most comprehensive commentary discussions, see Alan E. Brooke, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Johannine Epistles, in International Critical Commentary (New York: C. Scribner’s Sons, 1912), 154–165.

Tyler Robbins 2016 v2

Tyler Robbins is a bi-vocational pastor at Sleater Kinney Road Baptist Church, in Olympia WA. He also works in State government. He blogs as the Eccentric Fundamentalist.

- 235 views

There’s definitely a whole lot of “I believe it because I trust so and so and he believes it” in churches. I’m not sure how I feel about that. In some cases, we’re talking about folks who don’t have the education and/or cognitive skill level to work through that sort of study on their own. But there those who could acquire both the education (I’m not talking about seminary or even Bible college, just solid reading comprehension, grammar, vocabulary… history helps) and the cognitive skills. A third group pretty much has all the tools and resources but is just lazy.

Those in group a are in good company, historically speaking. For how many centuries were most Christians semi-literate or illiterate and lacking access to a copy of the Bible, much less a good systematic theology? So what did they do? They decided who they were going to trust and believed what they said (and used whatever analytical tests for internal consistency, etc., they could muster).

So there is something to be said for trust in godly leaders.

But the leaders are human and need “non leaders” who are strong enough to ask hard questions and evaluate the answers… and derive beliefs first hand. And everyone who can learn to study the Bible well independently should learn to do it and use that ability faithfully.

Views expressed are always my own and not my employer's, my church's, my family's, my neighbors', or my pets'. The house plants have authorized me to speak for them, however, and they always agree with me.

I actually took a group of 5th & 6th graders through a little bit on the Trinity a few weeks back….obviously not being able to walk them through the verb and noun endings, it was somewhat more difficult, but it’s surprising what you can do with a good look at Genesis 1 (mismatch of verb and noun forms means something), Psalm 110, John 1, and so on. It was a lot of fun and they got it. :^)

Aspiring to be a stick in the mud.

Psalm 110 is one of my favorite passages, along with Psalm 2 and the whole Book of Hebrews!

Tyler is a pastor in Olympia, WA and works in State government.

Kids often have less difficulty with the Trinity than adults because they don’t feel as much need to wrestle with the seeming contradictions. Since there is so much in life they accept but don’t understand, it’s par for the course. But if you quiz them carefully, you find out they’re view is quite often modalism or tritheism or one of the other common errors.

Not saying they can’t “get it,” but usually at a young age, you’re doing well if you manage to know what you don’t know. It’s OK to not get it.

(Most adults teaching the Trinity to kids also lapse into some sort of error. Some good thoughts at “The Trinity is Like 3-in-1 Shampoo”… And Other Stupid Statements)

Views expressed are always my own and not my employer's, my church's, my family's, my neighbors', or my pets'. The house plants have authorized me to speak for them, however, and they always agree with me.

[Aaron Blumer](Most adults teaching the Trinity to kids also lapse into some sort of error. Some good thoughts at “The Trinity is Like 3-in-1 Shampoo”… And Other Stupid Statements)

–––––––––––––––––––––

I’ve seen this video (produced by a LCMS pastor) several times, and it still makes me laugh:

I illustrated the fallacy of ice-water-steam by noting that one example of multiple persons with a profound unity would be their parents—and then by asking “if we heated up your dad, would he turn into your mom?” Agreed that there is a profound mystery of the Trinity that even adults have trouble with—I know I did—but it’s doable.

Aspiring to be a stick in the mud.

I’d appreciate some pushback on this if anybody disagrees with me.

I think ordinary people can understand the Trinity, as long as we stick to biblical theology. If you followed the recent Trinitarian kurfluffle over the idea of “eternal functional subordinationism,” you probably noticed that the issue stayed up in the clouds of systematic theology. Latin words were thrown out, and a few Greek ones, too. Creeds were invoked. Anathema’s were issued. Accusations of creedal betrayal were levied. Blah, blah, blah. I’m not completely denigrating that kind of discussion; in fact, that discussion prompted me to translate the Nicene-Constantinople Creed (381 A.D.) for myself for fun. (Yes, I’ve since found many mistakes in my translation which I haven’t fixed yet - have mercy on me, a sinner).

But, that kind of discussion can often leave a normal church member shaking his head, throwing up his hands, and ready to just accept what Pastor Biff said. I think this discussion needs to come out of the systematic clouds, and stay in the biblical theology of the actual text. This is what I’ll be doing with this series - starting in part 4. We’re going to just take an orthodox definition of the doctrine of the Trinity, and put it to the test through the whole Gospel of Mark. We’re going to see if the evidence fits the definition.

I think ordinary people can deal with this level of discussion. I tried it in my church, and it worked. I really think they can understand the Trinity, if they’re grounded in biblical theology before we start parsing the Greek verbs from Chalcedon! Honestly, we may never have to parse those verbs if we spend enough time walking through the text and unveiling the Trinity before their eyes.

If people can spend their spare time on any number of complicated and taxing hobbies, then they can understand the Trinity. I’m convinced of it.

Tyler is a pastor in Olympia, WA and works in State government.

It’s a little harder to get at the deity of the Holy Spirit, but it strikes me that another good example of applying Biblical theology is to take a look and ask what Jesus was doing when He was praying to the Father. If you understand things modalistically, you’re basically accusing Christ of talking to Himself—more or less saying He was mentally ill. But in a Trinitarian mindset, it makes sense.

I would also agree that all too often, theologicans fall into the traps laid in Westminster, Augsburg, and elsewhere by debating in terms of the theological shorthand/creeds instead of pointing to the real authority of Scripture. Not that the authors of either confession intended for this to be a trap, but the big danger of shorthand is that eye glaze over Tyler’s talking about.

The big thing I can see as a danger for getting more decent theology in the churches is sometimes (as I noted in the “things that will kill your church” thread) that people are so wed to the easy, prooftext or cultural answer, that you cannot get through with real theology. Not that it’s impossible, just “very difficult.”

Aspiring to be a stick in the mud.

One of the complicating factors in this discussion is that there are some theologians who assert the plurality statements seen in Scripture (particularly Genesis) are evidence (or at least an indicator) for the Trinity. However, Bible scholars (usually OT guys) reject that conclusion.

Consequently, there appears to be no consensus on this issue.

Example: Wayne Grudem, Systematic Theology, p. 227

For instance, according to Genesis 1:26, God said, “Let us make man in our image, after our likeness.” What do the plural verb (“let us”) and the plural pronoun (“our”) mean? Some have suggested they are plurals of majesty, a form of speech a king would use in saying, for example, “We are pleased to grant your request.” However, in Old Testament Hebrew there are no other examples of a monarch using plural verbs or plural pronouns of himself in such a “plural of majesty,” so this suggestion has no evidence to support it. Another suggestion is that God is here speaking to angels. But angels did not participate in the creation of man, nor was man created in the image and likeness of angels, so this suggestion is not convincing. The best explanation is that already in the first chapter of Genesis we have an indication of a plurality of persons in God himself. We are not told how many persons, and we have nothing approaching a complete doctrine of the Trinity, but it is implied thatmore than one person is involved. The same can be said of Genesis 3:22(“Behold, the man has become like one of us knowing good and evil”),Genesis 11:7 (“Come, let us go down, and there confuse their language”), and Isaiah 6:8 (“Whom shall I send, and who will go forus?”). (Note the combination of singular and plural in the same sentence in the last passage.)

Gordon J. Wenham, Genesis 1-15, WBC, p. 29:

The use of the plural(a) From Philo onward, Jewish commentators have generally held that the plural is used because God is addressing his heavenly court, i.e., the angels (cf. Isa 6:8). Among recent commentators, Skinner, von Rad, Zimmerli, Kline, Mettinger, Gispen, and Day prefer this explanation. Westermann thinks such a conception may lie behind this expression, but he really regards explanation (e) below as adequate.

(b) From the Epistle of Barnabas and Justin Martyr, who saw the plural as a reference to Christ (G. T. Armstrong, Die Genesis in der alten Kirche [Tübingen: Mohr, 1962] 39; R. McI. Wilson, “The Early History of the Exegesis of Gen 1:28,” Studia Patristica 1 [1957] 420–37), Christians have traditionally seen this verse as adumbrating the Trinity. It is now universally admitted that this was not what the plural meant to the original author.

…

(e) Joüon (114e) himself preferred the view that this was a plural of self-deliberation. Cassuto suggested that it is self-encouragement (cf.11:7; Ps 2:3). In this he is followed by the most recent commentators, e.g., Schmidt, Westermann, Steck, Gross, Dion.

(f) Clines (TB 19 [1968] 68–69), followed by Hasel (AUSS 13 [1975] 65–66) suggests that the plural is used because of plurality within the Godhead. God is addressing his Spirit who was present and active at the beginning of creation (1:2). Though this is a possibility (cf. Prov 8:22–31), it loses much of its plausibility if רוח is translated “wind” in verse2.

The choice then appears to lie between interpretations (a) “us” = God and angels or (e) plural of self-exhortation. Both are compatible with Hebrew monotheism. Interpretation (e) is uncertain, for parallels to this usage are very rare. “If we accept this view, it will not be for its merits, but for its comparative lack of disadvantages” (Clines TB 19 [1968] 68). On the other hand, I do not find the difficulties raised against (a) compelling. It is argued that the OT nowhere else compares man to the angels, nor suggests angelic cooperation in the work of creation. But when angels do appear in the OT they are frequently described as men (e.g., Gen 18:2). And in fact the use of the singular verb “create” in 1:27does, in fact, suggest that God worked alone in the creation of mankind. “Let us create man” should therefore be regarded as a divine announcement to the heavenly court, drawing the angelic host’s attention to the master stroke of creation, man. As Job 38:4, 7 puts it: “When I laid the foundation of the earth … all the sons of God shouted for joy” (cf.Luke 2:13–14).

If the writer of Genesis saw in the plural only an allusion to the angels, this is not to exclude interpretation (b) entirely as the sensus plenior of the passage. Certainly the NT sees Christ as active in creation with the Father, and this provided the foundation for the early Church to develop a trinitarian interpretation. But such insights were certainly beyond the horizon of the editor of Genesis (cf. W. S. LaSor, “Prophecy, Inspiration and Sensus Plenior,” TB 29 [1978] 49–60).

Thankfully, the Trinity does not stand or fall on one particular verse! The New Testament is extremely clear. I also saw some very intriguing passages from Zechariah when I was preaching through it earlier this year. This is truly a subject that one never finishes studying.

Tyler is a pastor in Olympia, WA and works in State government.

If the “us” in Genesis 1 is God + the court of angels, what then must we assume of “let us create man in our own image”? We would assume that we are made in part in the image of angels, a notion directly contradicted in other places in Scripture. No?

So we have to be careful with the notion that just because the original readers/writers would not have read it in a particular way, neither should we. For example, although I’m sure you’ll find very few Trinitarian explanations of Psalm 110:1 in the Talmuds, that is exactly how the Gospel writers, Paul, Luke, and the author of Hebrews use that passage. In the same way, John 2:22 and other passages show us that the disciples saw the previously hidden meaning of many things Christ had said only after He was resurrected.

In other words, an essentially literal, dispensational interpretation of the Scriptures is not incompatible with us seeing the meanings that even the writers and original readers did not get. We definitely have to be careful with it, but if we take the usage of Psalm 110 and John 2:22 seriously, neither is it something that we can a priori exclude.

Agreed wholeheartedly that one passage then does not make doctrine if we can at all avoid it—the further we can get from prooftexting, the better, in my opinion—but this is still one little piece of evidence of many that suggest significant OT support for the doctrine of the Trinity—or at least the deity of Christ.

Aspiring to be a stick in the mud.

[Bert Perry]Taught a SS lesson (adult) last Sun on the immutability of God. Didn’t use the word immutable at all, though I meant to tie it in at the end. I’ve seen many a lesson bomb because it trotted out the seminary vocabulary either too soon or when it really wasn’t needed at all. Also many doctrinal lessons are arranged & delivered with almost no tension at all. There is no central question or conflict or dilemma or puzzle or anything of the sort to give it forward pull. It’s just “here’s a bunch of facts.” No wonder people glaze over.It’s a little harder to get at the deity of the Holy Spirit, but it strikes me that another good example of applying Biblical theology is to take a look and ask what Jesus was doing when He was praying to the Father. If you understand things modalistically, you’re basically accusing Christ of talking to Himself—more or less saying He was mentally ill. But in a Trinitarian mindset, it makes sense.

I would also agree that all too often, theologicans fall into the traps laid in Westminster, Augsburg, and elsewhere by debating in terms of the theological shorthand/creeds instead of pointing to the real authority of Scripture. Not that the authors of either confession intended for this to be a trap, but the big danger of shorthand is that eye glaze over Tyler’s talking about.

The big thing I can see as a danger for getting more decent theology in the churches is sometimes (as I noted in the “things that will kill your church” thread) that people are so wed to the easy, prooftext or cultural answer, that you cannot get through with real theology. Not that it’s impossible, just “very difficult.”

Views expressed are always my own and not my employer's, my church's, my family's, my neighbors', or my pets'. The house plants have authorized me to speak for them, however, and they always agree with me.

Aaron ~ like the idea of not trotting out the big words too soon. It is a good reminder, and I agree with Tyler that people can get this stuff … if they are willing to study. Big words can be a difficult challenge, especially when they are labels that have been necessarily created to express biblical theology in a systematic format. But, for balance sake, I will mention this as well. When the Bible uses big words, you know, the “big, $.50 cent variety,” we should use them and not shy away from them. Teach, explain, and use.

I’ve actually found that if you explain them, you can use big words—even at the junior high level. The thing you’ve got to watch out for is the habit of simply dropping them around like pearls of wisdom when you’re pretty sure the recipients don’t understand them. Make it fun, make it historical, and they’ll remember.

Aspiring to be a stick in the mud.

James White provided the best and most helpful definition of the Trinity I’ve found:Within the one Being that is God, there exists eternally three co-equal and co-eternal persons, namely, the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit 2

This definition is excellent, because it captures five key things about the doctrine of the Trinity which every Christian needs to understand.3 Each of these facts are always true. In fact, this definition and the five implications should be memorized by every Christian:

Each Person is fully and completely divine4

Each Person has always been co-equal,5

Each Person has been around forever,6

Each Person is, in some way, distinct from the others, and yet

Each Person is, in some way, one with the others7

I saw this definition and my first thought was “But that definition doesn’t tell us what a ‘person’ actually is.” Then I looked up “person” in Wikipedia and found out something I didn’t know about the origin of the word “person,” that the concept was developed during the trinitarian debates.

“The concept of person was developed during the Trinitarian and Christological debates of the 4th and 5th centuries in contrast to the word nature.[2] During the theological debates, some philosophical tools (concepts) were needed so that the debates could be held on common basis to all theological schools. The purpose of the debate was to establish the relation, similarities and differences between the Λóγος/Verbum and God. The philosophical concept of person arose, taking the word “prosopon” (πρόσωπον) from the Greek theatre. Therefore, Christus (the Λóγος/Verbum) and God were defined as different “persons”. This concept was applied later to the Holy Ghost, the angels and to all human beings.

Discussion