Standard of Living?

One of the most telling characteristics of our culture is how we collectively determine an individual’s standard of living. The concept of a “standard of living” is something like a high-jump bar by which we gauge the quality of our daily lives. Some people cannot clear the bar and we say they experience a “low standard of living.” Others clear the bar with considerable room to spare and we declare that they enjoy a comparatively “high standard of living.” Those who fall between these two sub-sets keep jumping, but never seem quite sure if they clear the bar or not.

Irrespective of how high we are able to jump, one thing is certain: our culture naturally defines standard of living in terms of economic prosperity. The bar by which we gauge standard of living is hoisted to its current height by prevailing economic conditions and expectations and then we orient ourselves toward attaining that height—and then some.

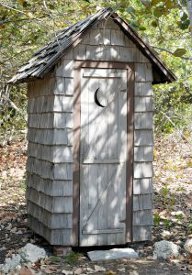

It is interesting to observe that the bar which distinguishes between high and the low standards of living has been steadily elevated throughout the latter half of this century. As case in point, I recently enjoyed an evening meal with my extended family. It was one of those summer time delights—grilled chicken breast, calico bean dish, corn on the cob, fresh baked rolls, potato salad and iced tea. Wow! The conversation among the elders at the table turned (as only an intimate family can turn it) to middle-of-the-winter trips to the outhouse. This topic veered off ever so naturally into a discussion of the history of toilet paper, when, on cue, my mother divulged her recurring account of the days her family could not afford said fibrous luxury. As the account always goes, she reminded us of the qualities of various alternative sources of “paper” that were used for this daily duty. (It seems that the wrapping on summer peaches was the paper of choice. My mother still speaks as if peach season were Nirvana.) I went home that night very thankful that the standard of living in America has improved so dramatically.

It is certainly not just toilet paper that has improved our living standard over the course of the twentieth century. Add to the list almost anything: from houses and cars to communication systems and the myriad of technological advances over previous generations.

Yes, in almost every way our standard of living has dramatically improved; if, that is, we blindly accept the prevailing criterion by which that standard is determined. I would like to propose that we should not so readily accept this criterion.

Without apparent thought, we assume that greater access to softer toilet paper, larger houses, fancier cars, enhanced technologies, etc., somehow constitutes a higher standard of living than was enjoyed in the past. In other words, we assume that economic improvements define our standard of living. I believe such thinking is misguided.

In light of experience and biblical revelation, I believe we need to learn to define standard of living in relational, not economic, terms. That is to say, we need to realize that the quality of our lives is not determined by material prosperity, but by relational prosperity.

When God established his covenant with the Israelites on Mt. Sinai, he summarized the Mosaic Law code in ten simple commandments. Not one of those commandments had anything to do with physical prosperity. All ten dealt with relationships. Jesus confirmed this thinking when he summarized the Mosaic Law as a life-quest to love God with all of our heart and to love our neighbor as we love ourselves (Matthew 22:34-40). In God’s way of thinking, it would appear, our standard of living is determined by how we love, not by what we have—by the worth and depth of our relationships, not by the ease of living we are able to carve out for ourselves.

To illustrate, we see too many children growing up in homes where interest in economic prosperity supersedes interest in building quality relationships between family members. It is a sad irony to watch a generation of parents trade intimacy with, and persistent daily training of, their children for the attainment of a supposedly higher “standard of living.” “What standard?” we might ask. “Whose standard?”

To illustrate again, how regrettable to see so many driven by the belief that winning the “jackpot” will provide an immediate, quantum leap to a higher standard of living. Anyone who believes that is deluded. If there is anything that can really mess up your relationships with others, it is coming into a large sum of money! In actuality, there is an astonishing record of misery that tends to follow those who win such “opportunity.” Or is it really that astonishing? Someone intending to realize a higher standard of living by means of a get-rich-quick scheme has a thing or two to learn about what kinds of things infuse quality into our lives.

My point is simply this: how you define standard of living has much to say about how you perceive life. In our context especially, it is vital that each of us work carefully on that definition. Somewhere on life’s journey we will all be stripped of physical wealth. The standard of living you will enjoy after that happens ought to be the standard of living you are pursuing with vigor before that happens. Forget about the prevailing definition, how do you define standard of living?

Pastor Dan Miller Bio

Dan Miller has served as the Senior Pastor of Eden Baptist Church since 1989. He graduated from Pillsbury Baptist Bible College in 1984 and his graduate degrees include the MA in history from Minnesota State University, MDiv and ThM from Central Baptist Theological Seminary and DMin from Trinity Evangelical Divinity School. Dan is married to Beth and the Lord has blessed them with four children: Ethan, Levi, Reed and Whitney.

- 6 views

Missionary in Brazil, author of "The Astonishing Adventures of Missionary Max" Online at: http://www.comingstobrazil.com http://cadernoteologico.wordpress.com

The danger in answering our society’s messed up social standards is that we’ll take on an unbiblically dim view of the material. God invented material, declared it to be good, made a man and told him to produce more of it. Interesting, isn’t it?

Views expressed are always my own and not my employer's, my church's, my family's, my neighbors', or my pets'. The house plants have authorized me to speak for them, however, and they always agree with me.

Discussion