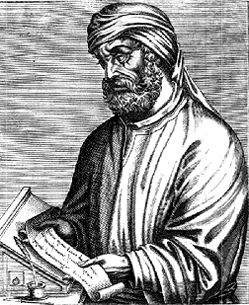

Tertullian Misses the Gospel

Tertullian was the first Latin theologian and one of the most creative minds of the second and early third centuries. In particular, his writings contributed greatly to later articulations of the Trinity. This essay focuses on the negative, but not because I think Tertullian was worthless or because I think all good Protestants should bash the Fathers to prove their orthodoxy. On the contrary, we Protestants could probably use quite a bit more familiarity with, and appreciation for, the first five centuries of Christianity. It is precisely because of how much I enjoy Tertullian that his sub-biblical gospel stings me so sharply. I’m writing this because I think we Christians could benefit from understanding how this powerful theologian and apologist came to his misunderstanding of the gospel.

Tertullian believes that there are several unforgivable sins—“murder, idolatry, fraud, apostasy, blasphemy; (and), of course, too, adultery and fornication; and if there be any other ‘violation of the temple of God’ ” (On Modesty, 19). To Protestants, this alone appears unnecessarily harsh, but Tertullian goes farther still. It is not that the Church (or at least the New Prophets, i.e., Montanists) lacks the power to forgive these sins, in Tertullian’s view; it does have the power, but it ought not forgive such sins (On Modesty, 21). Disregarding Tertullian’s scriptural arguments, which are intriguing, his practical argument is that such leniency will simply encourage more sin in the Church, which is clearly unacceptable. There are a few hints that perhaps God in His mercy will forgive the repentant, but in any case, they cannot be returned to the fellowship of the Church.

What a twisted view of the gospel! Yet, it is more profitable to explain the context of this error than simply to decry it. We must start with Tertullian’s view of the Church. He is a perfectionist, or very nearly so. The Church is the bride of Christ, so no spot or blemish should be allowed in it. Anyone who could be condemned by the outside world on moral grounds should have already been cast out of the assembly (Apology, 44). Tertullian’s apologetic strategy both presupposes and necessitates this perfectionist tendency. Tertullian’s main argument for Christianity is the moral blamelessness of Christians. According to Tertullian, Christians simply don’t engage in bad behavior, at least nothing too bad. Although he does grant that Christians may need one (and only one) dose of post-baptismal forgiveness for some non-mortal sin (On Repentance, 7), Tertullian does not paint a picture of Christians struggling against sin, except in an unending stream of victories.

Tertullian’s view of the Christian life is intertwined with his beliefs concerning baptism and repentance. A sinner should not approach baptism carelessly, but with faith and firm repentance in hand (On Repentance, 6). As Eric Osborn summarizes, “We are not baptized so that we may stop sinning, but because we have stopped sinning” (Tertullian, 171). For Tertullian, baptism washes away sin and original sin. Osborne explains that Tertullian believes that the human soul, as created, was originally good and that that good part remains in man. Original sin forms a second nature, both different and lower (On the Soul, 16, 41), that veils or blocks out the higher nature so that it is rarely seen. Baptism, then, removes the veil and enables the repentant sinner to make good on his commitment to the new life (Tertullian, 166-7).

Using a similar picture, I think of Tertullian’s doctrine of salvation in terms of two window washers. One day, both washers look at their windows and notice how dirty and ugly they are, covered with filth and almost entirely opaque. Acknowledging the sordid condition of their windows and resolving to do better, they turn to their manager, who has more powerful cleaning tools than they possess. The manager comes out and cleans their windows for them until they are spotless, transparent. He shows them how to use the tools and charges them to keep their windows clean. If a few specks of dirt happen to get on the window, they can clean it, but if the window should ever again resemble its filthy state, that washer may as well leave his tools and go home.

Under this arrangement, the first washer cheerfully begins to keep his window clean. As he goes along, though, he keeps noticing spots that he missed, or that seem to be reappearing whenever he moves on to another part. He begins scrubbing faster, but in his carelessness he seems to miss more and more spots. The dirty looks from the other washer only unravel him more. In desperation, he appeals to his friend, “Your window looks so clean! Can’t you help me with mine?” The other washer barks out a derisive laugh. “Ha! Help you? We’ve been given the same opportunity, and look how well I’m doing. If you were really trying, surely you’d be doing better than that. I could help you, but if I helped every window washer who asked me, I’d only be encouraging laziness. As for you, I’d rather you just give up and go home. We’ll find someone else who can live up to being a window washer.” So the frustrated washer does go home, wondering how he could have been doing so poorly when that other washer did so well. Unbeknown to him, the successful washer had only kept his window so clean by ignoring the bottom two inches, which had become so crusted with grime that the casual observer wouldn’t even realize that portion was supposed to be part of the window.

Tertullian in his perfectionism fails to understand the extent of the law—lust is as adultery, hatred as murder—and the purpose of the law—to lead men to cast themselves on Christ. To Tertullian, his repentance is the moral resolve of an unregenerate man, and his regeneration through baptism effects only a second chance with better equipment. His attitude toward repentant sinners is that of a haughty “older brother” who thinks he always keeps the Father’s commands. Although I am deeply thankful for his work on the Trinity and Christ, and for his refutation of heretics, I must conclude that Tertullian misses the gospel.

Charlie Johnson is a member of Downtown Presbyterian Church in Greenville, SC. He and his wife, Hannah, are graduates from Bob Jones University. He holds an MA in Theology from Greenville Presbyterian Theological Seminary and works teaching and tutoring while preparing for doctoral studies. He writes book reviews and reflections on Scripture at his blog, Sacra Pagina.

- 929 views

I saw alot of parallels between Tert’s way of thinking and some Fundamentalists I know! In their case, they believe the gospel, but also hold to attitudes about sin that are not compatible with it. Perhaps this was the case w/Tertullian also.

Views expressed are always my own and not my employer's, my church's, my family's, my neighbors', or my pets'. The house plants have authorized me to speak for them, however, and they always agree with me.

The whole notion of “missing the Gospel” is historically untenable. It assumes, among other things, that the “Gospel” Tertullian was missing was clear, articulate, and present in his context, and therefore it’s fair and not distorting to hold him accountable for “missing” it, just as we hold people accountable for not noticing something right in front of them due to inattention. If, however, the “Gospel” as Charlie is thinking of it was not clear, articulate, and present in Tertullian’s context than the whole idea of him “missing” it is an anachronism of the worst sort. If someone actually thinks the Protestant Reformation Gospel was “there” to be missed, then that is an equally bad if not worse form of anachronism.

Either way then, it’s at best irrelevant and at worst unfair to speak of Tertullian “missing the Gospel” in any straightforward sense. As many theologians have long noted, some people are seen in the light of developments that have made things clearer to have gone in a wrong direction, but we don’t, or should not, treat them the way we would treat someone who makes the “same” mistake in light of a much clearer understanding of truth and in the face of ecclesial rebuke. The latter person is a heretic, the former is not.

One reason Protestants do poorly with the Patristics is because you can deal with them in a serious and historically tenable way if you don’t have a developmental view of doctrine, which sounds relativistic to people who don’t understand it and, frankly, demands a historical consciousness Fundamentalists and most Americans in general have never exemplified. It’s a very “German” thing in its origins, although Newman saw the same issues from Great Britain without knowing any of the goings on in Germany in the 19th Century. The point is, besides the Mercersberg theologians (Nevin and Schaff), I don’t think conservative America theologians have ever come to grips with this issue. One evidence of this is that many people simply don’t understand this issue and thus don’t see it as an issue, including exactly the theologians who ought to know better (e.g. like professional historical theologians at our seminaries).

I know Charlie is not “going after” Tertullian; but the effect is, unfortunately, the same. If Tertullian missed anything, which he clearly did, one would have to go into his historical context to make a plausible case for where he mistakenly should have accepted x, y, and z rather than Montanism, etc. But x,y, and z would definitely not have been, in any historically relevant sense, the “Gospel.” Saying someone “missedsthe Gospel” is a severe charge and an enormously complicated one if it’s made about a historical figure who lived as long as a Tertullian.

1. Assuming that the Protestant articulation of the gospel is indeed the biblical one, all Christians (indeed all people) bear some measure of responsibility for embracing it and ordering their lives in accordance with it. Tertullian’s responsibility, due to his historical circumstances, is probably a lot less than those theologians’ at the Council of Trent. However, if there is development in doctrine, it is from the human side only. God has not changed, developed, or even expanded what he means by the gospel. I think there is probably a measure of methodological impasse between us in this way.

2. I am addressing Tertullian in his historical context. During his lifetime, there was a running controversy over post-baptismal sins - which were “mortal,” what you could do about them, how church leaders should address them, etc. Insofar as Tertullian chose the side in that debate that is farther from the biblical gospel, he expressed theological ideas that were contrary to gospel-informed reasoning, even by the standards of the early church.

3. My title and wording were deliberately ambiguous. As Aaron noted, genuine Christians can hold thoughts and attitudes contrary to the gospel. I think that people can be genuine believers with quite a few aberrations in their theology, even in their soteriology. However, expressing ideas that are out of accord with the gospel is very serious, and not the sort of thing that we can tolerate in ourselves or refuse to mark in others, even those early church Fathers living in a different era of “doctrinal development.” I think the proper Protestant stance toward the church Fathers is somewhat ambiguous - heartfelt gratitude mixed with serious reservation.

My Blog: http://dearreaderblog.com

Cor meum tibi offero Domine prompte et sincere. ~ John Calvin

SI isn’t the forum for an in-depth exchange about this, so I’ll just offer responses to your three points, in inverted order.

3.”Heartfelt gratitude mixed with serious reservation” is sufficiently vague to be uncontroversial to me, although I suspect I would have eventual problems with how “serious reservations” plays out. Any serious reservations I would have about the Fathers, as the group that shaped the theological and ecclesial shape of the early church, are along the lines of the “serious reservations” I might have about a plane that just successfully flew me from the US to China - I could not have gotten there without it, even if I wish some things were different, etc. The analogy is limited; the main point is that the Fathers are an indispensable and necessary part of the church’s development, and any position that can’t make sense of this is to that extent not part of the “one, holy catholic and apostolic church.” I don’t think most conservative evangelicals (including Fundamentalists) can make sense this, hence the thinness and historical shallowness of their theological work.

2. Sounds ok to me, although the use of “biblical Gospel” seems to be begging the question.

1. This just seems to be a way of saying you fundamentally either don’t understand what I’m saying or don’t have any substantive belief in doctrinal development, since it assumes everything I cited as anachronistic, viz. the idea that the Protestant Gospel is just there to be known, which is historically rubbish - it wasn’t. It was “discovered” and even then in a context that most contemporary Protestants would find “too Catholic.” Calvin was possible because of Luther, et al. who were in turn possible because of a host of contingent historical and theological factors.

I’m not sure I understand the “God doesn’t change,” etc. part, as I don’t see how doctrinal development has anything to do with beliefs about God’s impassibility, etc. If you mean God didn’t develop or expand what he means by the Gospel in his revelation to human beings then that is just patently false, as it would make pure rubbish and idolatry of Judaism, whose history from Abraham ot Christ is most definitely a history of God’s progressive revelation of what the Gospel means and who God is. One does not have to believe in critical reconstructions of Judaism’s history to know, as any good OT scholar would confirm, that there was immense development in Judaism’s idea of God, the messiah, the Davidic kingdom, and a host of other things.

Christianity is essentially and radically a historical religion; there is an important sense in which it has always understood itself as such. But after the rise of historical consciousness and the crucial ways that intersects with and shapes historical-critical studies of texts, including Scripture, this became clearer than it had ever been in history, and it really took the Twentieth century, the Holocaust, and the Third Quest (so-called) for most Christians to finally own up to how crucial Judaism is for Christianity and for Jesus himself, for example. That’s two thousand years; it took until roughly the Renaissance century for people to finally understand the past as past (e.g. see Peter Burke’s The Renaissance Sense of the Past), and even longer until that became widespread in historical study.

There was nothing inevitable or universal about these developments; the fact that most people, including those who live in the societies that made these discoveries and advances in consciousness, do not understand them simply illustrates that point.

I think we are afraid to let the pastness of the past be a reality to people (with some justification), but the result of that fear or simple inability is a distortion of the past. I understand that, too, and there are no easy solutions to the problems history raises; but, unfortunately, Christians need to deal with this, and only the ones who do can do profound historical work on the church’s past. As I said, we don’t have many of these in American conservative Protestantism.

First, I think (probably not a good idea, but can’t help myself…) that you’re saying that the gospel has in fact changed. Better put, those things that each person is called to believe for salvation have been revealed to different extents at different times. All believers have been given grace to trust the promises of God. But the details and scope of the promises of God has not always been revealed or understood to equivalent extents.

*** Not agreeing or disagreeing at this point, just seeking to understand ***

The other basis seems to be that you read “missed” as “just barely missed” or “missed despite it staring him in the face.” Why not read it as “didn’t correctly or completely apprehend?”

I think that even if you do read it the way you did, I think there is still call to say that he has missed it. Certainly, we stand on the shoulders of giants and we shouldn’t arrogantly think that we would have the view we have without them. But how would it be wrong to judge Tertullian by the view properly afforded by his giants? He had David. He had Paul. Surely, even if he didn’t understand Paul, the life of David could have told him that there is forgiveness for murder and adultery. Perhaps Tertullian stood too much on the shoulders of his legal training and not enough on the shoulders of the Scriptures, through which we have hope.

I will also take issue with your Airplane to China analogy. To me, it is a bit more like the taxi in Connecticut that takes you to airport, but runs the meter up for an hour before dropping you off, in the process making you miss your flight and then you have to catch one the next day (or in 1500 years). Then the airplane takes you to China and you’re thankful to the Taxi?

-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-

Charlie,

Tertullian’s view of personal perfectionism in salvation seems to mirror the growing ecclesiastical perfectionism seen in the bishops, especially the Roman bishop. In other words, considering the sentence, “X really should be true in the life of Y,” where X=(forsaking sin, teaching correct doctrine) and Y=(a believer, churches led by Bishops in the apostolic tradition-especially Rome). Tertullian (but more Cyprian and Iraneus) would read “should” as a guarantee from God, where I would read “should” as an obligation.

[Joseph]You’re right, I don’t. I’m far more inclined to filter history through a theological grid than vice versa. I don’t put very much stock in doctrinal development, and I don’t think it’s incidental that you mentioned Newman, whose turn from Protestant to Catholic is considerably intermingled with his views on the history of doctrine. I’m not much for historical consciousness or any of the mainstream developments post-Lessing. I don’t think that what people should believe about Scripture, God, and Christ has changed much since 90 AD.

1. This just seems to be a way of saying you fundamentally either don’t understand what I’m saying or don’t have any substantive belief in doctrinal development

My Blog: http://dearreaderblog.com

Cor meum tibi offero Domine prompte et sincere. ~ John Calvin

Also, I’m not sure about what you meant by your last paragraph. I don’t know of any early church father that would say that all bishops, or even the Roman bishop, had reached perfection or even always taught the truth. They deposed bishops all the time (John Chrysostom for example) and one Pope (Honorius III I believe) was declared a heretic. All the way into the Middle Ages the status of the bishops and the Pope in relation to the church was hotly debated by Ockham, Marsilio, Wyclif, and Hus. I don’t think until Vatican Council 1 the Pope we see the Pope as we know him today.

My Blog: http://dearreaderblog.com

Cor meum tibi offero Domine prompte et sincere. ~ John Calvin

Might be redundant to say so at this point but, yes, we believe here that the gospel we embrace now was and has always been the gospel that had to embraced. So if T. missed the gospel as we know it, he missed the gospel, period.

But I’ll still cut him this much slack: people hold to mutually exclusive ideas all the time. That is, people are not logically consistent (which has to include me though I don’t like to think so). Even smart people.

The result is that though they may state beliefs in one place that are not compatible with the gospel, they may still believe the gospel… they just aren’t seeing the disjunction.

Perhaps that’s where there is room for development-of-doctrine factors, “anachronism,” etc. It may be fair to say that what students of the Bible figured out later included recognizing certain ways of thinking were not compatible w/the gospel and had to be rejected.

But still, Paul pretty much spelled it all out in Romans, and Galatians, and Philippians, and… and…

So I’m inclined to say it’s not a dev. of doctrine issue so much as a failure to think it through issue, at best. At worst, T. was just a plain old legalist.

Views expressed are always my own and not my employer's, my church's, my family's, my neighbors', or my pets'. The house plants have authorized me to speak for them, however, and they always agree with me.

"Our task today is to tell people — who no longer know what sin is...no longer see themselves as sinners, and no longer have room for these categories — that Christ died for sins of which they do not think they’re guilty." - David Wells

I’ve indicated that SI isn’t the right context for a thorough discussion of this, and I just want to repeat that so people don’t misunderstand what I expect from my comments. E.g. I don’t expect to change anyone’s mind, for example, or for people to understand what I’m saying exactly.

I think I would agree with your “better put” statement, but I would also probably agree that the Gospel has changed, if and only if people sufficiently appreciated what saying that does not mean. Let me just offer a precis of what I think the statement involves. If you say “the Gospel changes” you have an enormously ambiguous statement, but it’s grammatical structure implies at least two things that set that statement apart from certain other statements that some might wrongly think are entailed by it.

If “the Gospel” changes, there is a single, self-same, unitary subject that in some ways maintains its identity, its self-sameness, while also not remaining static. There is thus no question here of there being multiple Gospels, one for x and another for y, which is what some might think such a statement entails - but, again, they would be quite wrong. It’s helpful to see an analagous statement: “Charlie changes.” Of course Charlie changes: it’s the nature of human beings, which are biological organisms (among other things) and subject to history, that they do so. But Charlie is still Charlie. A lot of the same difficulties that arise in making sense of statements like “the Gospel changes” arise in the philosophy of personal identity (e.g. see Parfit’s book on Persons), viz. how you account for identity through change. But the point is everyone knows humans change and that they also, in some very important sense, remain the same. The issue with the Gospel is similar (although I have not even touched what we mean by the Gospel; I’m just drawing attention to the grammar of the statement); there are differences, too, but the grammatical problems are the same.

With respect to the Fathers, I’m one of those (who historically are the mainstream, incidentally) who don’t see the history of the early church as “accidental,” and thus the Fathers in particular play an essential role in our being where we are and in constituting Christian identity. Jaroslav Pelikan spent his life combating the idea that we could “skip” the people who formulated our most fundamental doctrines by just snatching the formulae and saying, “yep, they are Scriptural but never mind Athanasisu and Gregory….” I agree with Pelikan.

Finally, with respect to Tertullian “missing” anything, I repeat what I said: it’s only just to speak of someone “missing x” if x, as the person who is making the judgment “He missed x” understands x, could be relevantly said to be available to the person. As I said, Tertullian was seen to have missed something, as were all of the Montanists, but that does not justify a statement like “Tertullian missed the Gospel.” This is especially the case since many of the post facto heretic condemnations (e.g. of Origen) are seen now, in retrospect, to be unfair if understandable.

A couple of questions for you that I hope you will try to give a clear answer for our better understanding of your position.

1. How has the gospel changed?

2. What was not available to the church fathers that is available to us, in terms of the biblical revelation about the gospel?

From where I sit, statements like “I’m far more inclined to filter history through a theological grid than vice versa” don’t make a lot of sense. Nor does not putting “stock in doctrinal development make sense” make sense to me, although I understand what you mean in saying these things. Historical consciousness is an achievement, like reading, that is irreversible by its nature; you can’t not see certain things as intelligible after the transformation, although you also never stop seeing them as little black squiggly marks. So there is no issue of “believing in it” or “putting stock in it.” One is either in a position in which one sees the problem to which doctrinal development is an attempted solution or one is not. If one is not, one will simply find the issue close to pointless, etc. and not put much stock in it. If one does understand the problems that it attempts to deal with there can be no question of putting stock in it: it is there, the only question is how to deal with it, make sense of it, etc.

Few people in American orthodox Protestant theology historically have seen these issues, which is one reason Nevin and Schaff, for example, are simply incomprehensible in a lot of their concerns to modern Presbyterians, including many of the scholars who write on them, who simply do not know or understand the thinkers (e.g. German romantics and Idealists) and problems (issues of historical consciouness, development, etc.) that they were concerned with. It’s for this same reason - and this is something many Americans just don’t understand - that many European theologians or “German” American liberal theologians simply don’t engage with a lot of American theology; it plain to them that we don’t get a lot of the background that frames the issues they attend to and the way in which they attend to them.

There is no way of frankly dealing with this kind of disagreement on these and analagous issues without sounding “elitist” or “esoteric” because, in fact, disagreement is not what is happening here. Charlie and I don’t disagree because we’re not attending to the same thing. Unlike some of the people on whom I work (e.g. FIchte), I don’t think the issue is ultimately one of elitism or esotericism, where only a few people, in principle, understand what’s going on. I think, in principle, practically anyone can understand them but in practice there is 1) no way of ensuring this happens to a person and 2) there is no direct way of communicating the issue, because the issue is not about something or other, it’s about a kind of consciousness that characterizes one’s identity and thus one’s relation to the world.

As Burke, in the book I mentioned, shows, even understanding “anachronism” is a major achievement of consciousness that was not part of Medieval theology, just as i don’t think it’s part of many people’s understanding today.

I don’t see any of this is horrible or meaning we collectively can’t do good and valuable work; we can, have, and continue to do so. We just don’t do a certain kind of work very well and thus we don’t really engage with a lot of issues that others regard as fundamental.

Joseph, I’d also like to see you respond to Larry’s questions.

Views expressed are always my own and not my employer's, my church's, my family's, my neighbors', or my pets'. The house plants have authorized me to speak for them, however, and they always agree with me.

I won’t engage those questions and don’t feel a need to explain why beyond my last post, as well as for time reasons. Still, here are two other reasons, neither of which I’m going defend - I’m just stating them.

1. I don’t know what you think you mean by those questions, but to me the are questions of the scale on which you need to read hundreds of books to understand in any profound way what is at issue and in response to which a monograph study, in terms of depth and coverage, is the only appropriate answer. That is why I only touched on the grammar of the statement “the Gospel changes,” which grammar itself, as I alluded to, has received an enormous amount of highly technical and complex treatment - and it’s also why I said I would say the Gospel changes “if and only if…” - which you seemed to ignore. My entire discussion of the issue was hypothetical, and your question assumes the very proposition that I said I would not affirm except under certain strict conditions that don’t here obtain.

2. ‘In light of that, I reject the way you formulate the questions, especially the first. It indicates that we are nowhere close to being on the same page (e.g. you didn’t even attend carefully to what I wrote), which is one reason answering them would require so much effort. More than half the effort would need to be spent on understanding what is being asked. In fact, that kind of question is the kind of question that is appropriate at the end of a chapter, or even a book, length exposition that frames and gives a determinate sense to what the question is doing.

This happens frequently on SI, so I”m not surprised by it nor do I feel badly about it: not everything can be meaningfully and constructively discussed on a forum, and it’s imprudent not to signal when one thinks such an issue is arising.

I’ve already spent a good bit of my time already thinking and writing about these issues and wondering how, pedagogically, I’m going to communicate them to students. Suffice it to say that I seriously doubt whether any one-semester course would have a high probabilty of bringing about the desired outcome, viz. a certain quality of understanding, even if at a very inchoate level. I hope that maybe at the end of a sequence of courses some students might come to appreciate some of these problems. That is the kind of scale on which I see this issue, so it’s simply ridiculous for me to pretend we’re going to have a meaningful discussion about it on a forum.

Calvin was possible because of Luther, et al. who were in turn possible because of a host of contingent historical and theological factors.I would argue that Luther and Calvin were possible because of Paul, although they may have gotten there partly through Augustine.

This entire discussion argues well my case, namely, finding our “roots” in the church fathers is pretty much a futile direction. They did, in fact, make some good observations and did accumulate doctrinal summaries that were more holistic (like the Trinity as the prime example, or the hypostatic union). But, theologically, we are better served if we return to the Jewish roots of our faith. As Charlie pointed out, even a great mind like Tertullian whose work on the Trinity is monumental, was groping. The early Jewish believers (particulary those influenced by the School of Hillel, the ethics Jesus and Paul seemed to match in many ways) understood the concept of mercy and forgiveness so much better than Tertullian. Jewish believers were in the majority until 68 A.D., and the church went down hill as the gentiles — who did not have the Jewish assumptions of the early believers — took charge.

"The Midrash Detective"

Discussion