From the Archives – Using the London Baptist Confession of 1646 in the Local Church

Image

Reformed Baptists are drawn to the London Baptist Confession of 1689 (originally issued in 1677) because it so closely mirrored the popular Presbyterian Westminster Confession of Faith. But the first two London Baptist confessions of 1644/1646 offer a window into history and a resource for Baptists today that is slightly different in its emphases. The London Baptist Confession of 1646 is Reformed and Baptist in its theology while emphasizing the newness of the New Covenant era that began with Christ. This article explores some of the benefits and challenges of using the London Baptist Confession of 1646 in the local church today.

Appealing Qualities

There are three appealing qualities of this Confession that are worthy of highlighting.

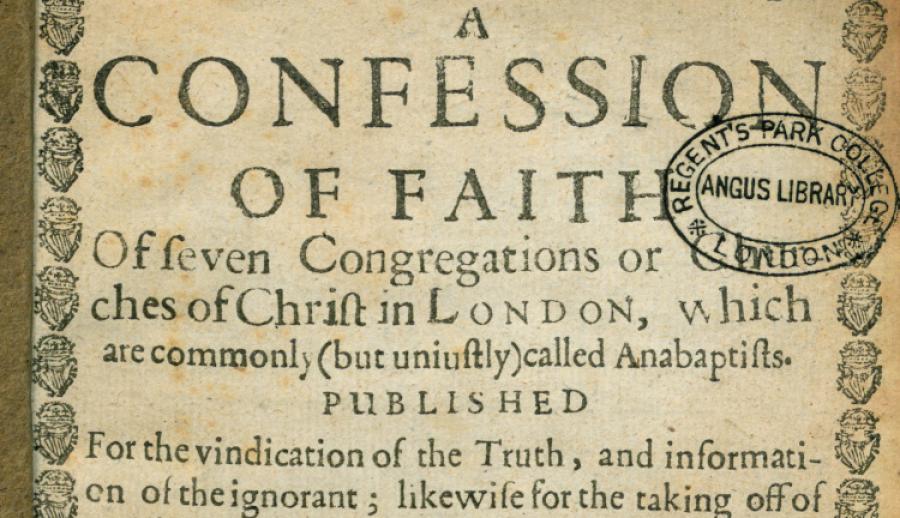

The Confession was originally drawn up and signed by seven churches in London in 1646. This was a “corrected and enlarged” edition of the first confession, published in 1644. The title of the original Confession of 1646 was: “A Confession of Faith of Seven Congregations or Churches of Christ in London, Which are commonly (But Unjustly) Called Anabaptists.” A copy of the original Confession of 1646 is widely available on the internet. An edition printed by Matthew Simmons and John Hancock in Popes-head Alley, London, 1646 is available online from The Angus Library and Archive at Regent’s Park College, University of Oxford.

One area in which the Confession is appealing is the absence of a doctrine about Christian Sabbath-keeping. This is an area in which Calvinistic Baptists have historically been divided. Other confessions such as the London Baptist Confession of 1689 view the Lord’s Day (Sunday) as the equivalent of the Sabbath as found in the Ten Commandments and the only acceptable day for corporate worship. In contrast, the London Baptist Confession of 1646 does not address the Sabbath. The Confession of 1646 stresses the newness of the New Covenant era with respect to the use of Law of Moses. Some strands of Reformed theology over-emphasize continuity between the New Covenant era and the Mosaic era, but the Confession of 1646 offers a valuable alternative that is silent on the matter.

A second area in which this Confession is appealing is the identity of the anti-Christ. The London Baptist Confession of 1689 explicitly identifies the Pope of Rome as “that antichrist” (chapter 26, paragraph 4). Today, this statement is sometimes qualified or re-written so that the article is wider in scope or applicable to more persons than the Pope of Rome. In contrast, the London Baptist Confession of 1646 does not attempt such an identification of the antichrist. In hermeneutics, it is axiomatic that the meaning of the biblical text is singular and does not change whereas the application of the text is many. Wisdom also dictates that a confession of faith should avoid applications of texts that may not endure in future generations. The point is that the antichrist concept may include more individuals than the Pope and so it remains an area of weakness in the Confession of 1689. The Confession of 1646 allows local churches to make this application without finalizing and making their application permanent it in a statement of faith.

A third area that will be of interest is the Confession’s approach to the difficult doctrine of limited atonement or particular redemption. The Confession rigorously integrates the sovereignty of God in salvation throughout all of the articles. When it comes to the specific topic of atonement in article 21, it addresses Christ’s work on behalf the elect. It does not offer an overly narrow definition of Christ’s objective accomplishment on the cross, but rather focuses on the narrowness of how this atonement is applied to the elect. This focus on the application of the atonement toward the elect opens this Confession to the nuances of the doctrine of atonement as found within Reformed thought and doctrine (see Thomas’ monograph: The Extent of the Atonement). This makes the 1646 Confession appropriate for a range of Baptists seeking unity in core doctrines while offering flexibility in secondary areas where there is disagreement.

Briefly stated, the strength of the London Baptist Confession of 1646 is that it offers a Reformed and historical Baptist confession that is substantially different from the popular 1689 confession in the areas of Sabbatarianism and the doctrine of Limited Atonement. Where others (e.g. Shawn Wright in 9Marks) have questioned the “wisdom” of using the 1689, the 1646 edition offers a strong and perhaps wise” alternative for use in the local church.

Challenging Aspects

Local churches who want to use the Confession today should first consider these four challenges.

The first challenge is its omission of statements on the doctrine of Scripture that subsequent debates now require. The Confession of 1646 addresses the doctrine of Scripture but this topic is sometimes assumed rather than explained. The Confession celebrates the truthfulness and excellence of Scripture, but it nowhere identifies the Bible as inerrant or even inspired. However, these concepts are certainly present even if the terms are not used. There are references to the nature of faith in relation to God’s “revealed or written word” (article 22), the centrality of preaching the word of God (article 44), and the concept of the authority of the Old and New Testament (article 49), etc. This issue might be addressed by supplementing the Confession with the Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy.

Second, the doctrine of the Holy Spirit, his person and work, is not singularly addressed in any article. Like the doctrine of Scripture, a close reading of the articles in the Confession will demonstrate that the doctrine of the Holy Spirit is found in many places. Rather than having a dedicated article, the doctrine of the person and work of the Holy Spirit is woven throughout. He is referenced at least fourteen times and is given specific attention in articles 1 and 2 in relation to the doctrine of God. The doctrine of the Holy Spirit is actually robust when all of the statements in the Confession are considered together.

Third, the Confession does not address human sexuality and the roles of men and women in marriage. The requirement for elders or pastors to be men is clearly stated in article 44, but the topic of human sexuality and the role of women in the church was simply not a major issue at the time this Confession was originally written. But the cultural and legal context of the world today requires that churches have a clear written statement about these matters. This omission might be addressed by adopting The Danver’s Statement by the Council on Biblical Manhood and Womanhood.

Fourth, the Confession is rather long compared to contemporary denominational statements of faith. The length of any confession is a double-edged sword. If a confession is too detailed, it can become impractical for use in a local church with people who have varying levels of theological training. But if a confession is too short, it can lead to division, confusion, and deviant doctrine. For example, some churches may be uncomfortable with the lack of detail in this Confession regarding the “end times.” Some Christians will perceive this silence as an opportunity for Christian unity.

Conclusion

A modern version in booklet form is available from Ambassador International press, edited by David H. Wenkel, PhD (Aberdeen, Scotland). The goal of this modern edition is to maintain the meaning and message of the original Confession while presenting it a new way for today’s readers in the local church. The preface of this booklet explains all of the changes that were made in the editorial process. A sample PDF and more information can be found at: www.reformedbaptistconfession.org. A historically accurate and academic copy with all of the original elements is available through Particular Baptist Press.

David Wenkel Bio

David H. Wenkel enjoys supporting theologically-minded pastors and pastorally-minded theologians. He holds a PhD in NT theology from Univ. of Aberdeen, Scotland, as well as ThM and MA from Trinity Evangelical Divinity School. He serves as adjunct faculty in Bible at a couple of seminaries.

- 259 views

Read the article and the creed. The article’s points are good, it is better than the 1689 in many ways, but needs the recommended supplementing.

Here is a link to the creed: http://www.reformedreader.org/ccc/1646lbc.htm

"The Midrash Detective"

One area in which the Confession is appealing is the absence of a doctrine about Christian Sabbath-keeping. This is an area in which Calvinistic Baptists have historically been divided. Other confessions such as the London Baptist Confession of 1689 view the Lord’s Day (Sunday) as the equivalent of the Sabbath as found in the Ten Commandments and the only acceptable day for corporate worship. In contrast, the London Baptist Confession of 1646 does not address the Sabbath.

This article seems to imply that the 1LBC had a more discontinuous view of the Sabbath than the later 2LBC Baptists, similar to New Covenant and Dispensational folk.

I wonder if that’s the case, though. As I recall, the Seventh-Day Baptists (who view Saturday rather than Sunday as the “true Christian Sabbath”) originated around this time. Or at least, the first historical records of them date to the 1650s. I wonder to what degree their story played a role in this omission. Would be curious to find out.

Andrew wrote:

This article seems to imply that the 1LBC had a more discontinuous view of the Sabbath than the later 2LBC Baptists, similar to New Covenant and Dispensational folk.

I didn’t read it that way. I understood the comments to mean that it was more USEFUL to those of us who don’t hold to a Christian Sabbath Day, not that they didn’t believe that. They just didn’t address it.

"The Midrash Detective"

[Ed Vasicek]Andrew wrote:

This article seems to imply that the 1LBC had a more discontinuous view of the Sabbath than the later 2LBC Baptists, similar to New Covenant and Dispensational folk.

I didn’t read it that way. I understood the comments to mean that it was more USEFUL to those of us who don’t hold to a Christian Sabbath Day, not that they didn’t believe that. They just didn’t address it.

Possibly, but I took it from this sentence: “This is an area in which Calvinistic Baptists have historically been divided.”

Discussion