Ties of Fundamentalism and Premillennialism

Image

Thomas Ice

Republished from Voice, Jan/Feb 2020.

While all fundamentalists have not been premillennial, the overwhelming majority have been. Premillennialism has been a historic staple of fundamentalism. It is often the case that when one abandons the fundamentals of the faith, they also abandon the premillennial hope. Why has that been the case in the past and why should it continue into the future, especially within the IFCA?

Post-Civil War Rise of Fundamentalism

Postmillennialism in America arose as the dominant eschatology in the 1720s as a result of the influence of theologians like Jonathan Edwards and dominated evangelicalism until a decade or two after the Civil War. Higher critical liberal scholarship began to cross the Atlantic and make progress in America by the 1880s, which lead to the rise of fundamentalism as a response by conservative evangelicals. “Dispensationalism, or dispensational premillennialism, was the fruit of renewed interest in the detail of biblical prophecy which developed after the Civil War,” observes George Marsden. “Rejecting the prevailing postmillennialism… dispensational premillennialists said that the churches and culture were declining and that Christians would see Christ’s kingdom only after he personally returned to rule in Jerusalem.”1

It appears that fundamentalism is simply the continuation of historic orthodox Christianity as expressed within the context of a changing American Christianity that had its beginnings in the second half of the nineteenth century in response to the rise of liberalism within American Protestantism. Fundamentalism has been “a self-conscious interdenominational movement from 1857 to the present.”2 It was the Bible Conference movement that began to coalesce true conservatives into a movement. The movement began in 1875 with the first meeting in Niagara in New York. “Meeting for two weeks each summer, the Niagara Conferences provided a gathering place for conservative evangelicals to hear the older evangelical doctrines confirmed and preached,” notes Timothy Weber. “The new premillennialists were at the Niagara Conferences from the beginning and eventually became the dominant force in their leadership.”3 Such gatherings became a source for the furtherance of the fundamentalist premillennial faith up until the beginning of the twentieth century.

John Nelson Darby and other Brethren brought dispensationalism to America through their many trips and writings that came across the Atlantic. It was primarily within the orbit of Reformed denominations that produced the fundamentalist premillennialism that would dominate conservative Protestants for the next century. “In fact, the millenarian (or dispensational premillennial) movement,” declares Marsden, “had strong Calvinistic ties in its American origins.”4 The Reformed historian continues his explanation of how dispensational-ism came to America:

This enthusiasm came largely from clergymen with strong Calvinistic views, principally Presbyterians and Baptists in the northern United States. The evident basis for this affinity was that in most respects Darby was himself an unrelenting Calvinist. His interpretation of the Bible and of history rested firmly on the massive pillar of divine sovereignty, placing as little value as possible on human ability.5

There were fundamentalists in virtually every denomination in the United States since ‘the focus was on maintaining the historic Christian faith. “In 1910 the Presbyterian General Assembly … adopted a five-point declaration of ‘essential’ doctrines,” notes Marsden. “Summarized, these points were: (1) the inerrancy of Scripture, (2) the Virgin Birth of Christ, (3) his substitutionary atonement, (4) his bodily resurrection, and (5) the authority of the miracles.”6 In most instances, premillennialism was also considered a fundamental of the faith as noted by Marsden: “they became the basis of what (with premillennialism substituted for the authenticity of the miracles) were long known as the ‘five points of fundamentalism?”7

Why did premillennialism become such an important doctrine for the early fundamentalists? The importance of premillennialism spoke to the clearness of Scripture and the issue of the miraculous, which is why it eventually displaced miracles as the fifth point of the fundamentals of the faith. Early dispensationalists believed strongly in the essential clarity of Scripture. God, who created human language, could and did reveal Himself clearly in Scripture. In an intellectual climate of ever-increasing Darwinian influence in the first half of the twentieth century fundamentalists “were militantly committed to an essentially supernatural, biblically based, traditional faith.”8

This would mean that premillennialism was front-and-center in such a struggle. Belief in premillennialism meant that one took the Bible literally when it referred to God’s foreordained plan for history. “The strong link that developed between premillennialism and conservative-evangelical Protestantism in America helped spread the belief in the Second Coming.”9 It was the fundamentalist who brought premillennialism to the forefront as an essential of the faith in the early 1900s because of the attack on the Bible by liberals who mocked a literal interpretation of God’s Word. If one interprets the Bible literally, the way it was intended when written, then premillennialism had to be the obvious outcome.

Early Twentieth Century Premillennialism

With the turn of the century and events leading to World War I, premillennialism began to make significant gains within American evangelicalism. It was becoming clear from the events of history that Christendom was not leading to the Christianization of America, let alone the world. “The resurgence of millenarian interest during the world war,…distressed many liberals,”10 notes Ernest Sandeen. Liberals were beginning to take note of the impact of premillennial fundamentalism. Shirley Jackson Case, a liberal professor at the University of Chicago Divinity School wrote a response to premillennialism entitled The Millennial Hope, (1918), which sounds like it could be a case for premillennialism, but it was a presentation advocating for postmillennialism and extremely critical of premillennialism. Even though postmillennialism had enjoyed dominance within evangelical Christianity in America since the days of Jonathan Edwards, it was in the process of almost dying out as a result of the Civil War and two subsequent World Wars. As a result, liberals became amillenninal and conservatives premillennial.

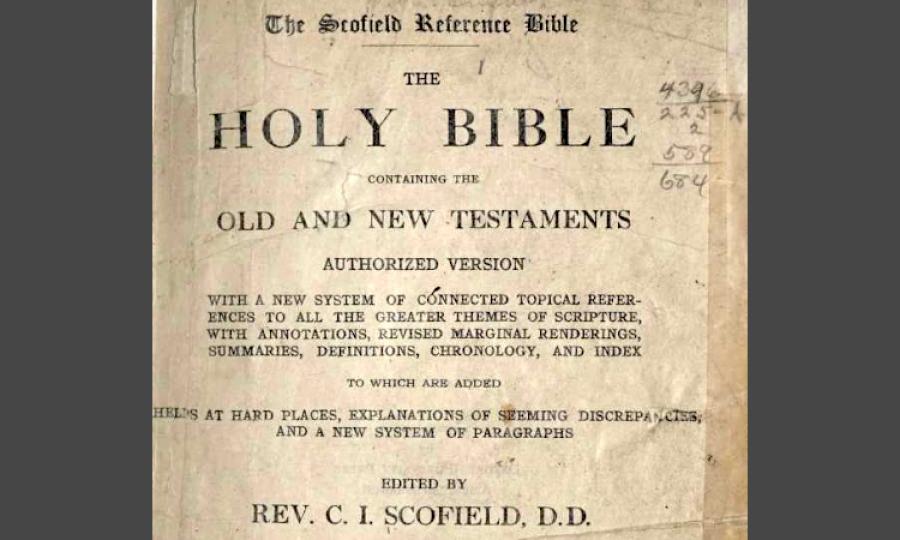

“The year 1925 was a grim one for American Fundamentalism.”11 The famous Scopes trial dealing with evolution was proclaimed by the national media as an embarrassment for fundamentalist Christianity. However, in 1909 (revised, 1917) The Scofield Reference Bible was published. “Oxford University Press released that Bible on January 12, 1909, and, within two years, two million copies had been published.”12 C. I. Scofield produced notes in his Bible that taught dispensational premillennialism and the pretribulational rapture. As indicated by the amazing sales throughout the next sixty years, Scofield’s Bible spread far-and-wide as did belief in dispensational, premillennialism, and pretribulationism.

The IFCA came into existence in 1929 and as a fellowship of fundamentalist churches has always held to premillennialism as a required tenet for membership. Some of the most outstanding advocates of premillennialism have been members of the IFCA over the years. The list includes such stalwarts as J. Oliver Buswell, M. R. DeHaan, Louis Talbot, Charles Feinberg, John Walvoord, J. Vernon McGee, Merrill Unger, Charles Ryrie, and John MacArthur. While some other organizations and schools have abandoned premillennialism in recent times, the IFCA remains totally committed to premillennialism as a fundamental of the faith.

Contemporary Premillennialism

Premillennialism probably reached its peak of popularity in America during the 1960’s and 70’s because of the amazing growth of evangelical churches and influence. The early 70’s saw explosive growth within evangelicalism, largely due to the revival during the Jesus movement.” Dispensational Bible prophecy was front and center during the Jesus movement fueled by books like Hal Lindsey’s The Late Great Planet Earth and the movie series A Thief in the Night. Tim LaHaye’s multiple novels in the Left Behind series that sold over 80 million copies in the late 1990’s and early 2000’s reignited both premillennialism and pretribulationism within American Christianity. In spite of the novel’s success premillennialism appears in decline following the pattern of overall decline of evangelical Christianity in the United States since the beginning of the new millennium.

There has been in every generation of America, since the Pilgrims and Puritans first arrived in the early 1600’s, some kind of revival or spiritual awakening, whether national or localized. It has been about forty-five years since America’s last revival—the Jesus Movement (about 1968-75). Both fundamentalism and premillennialism historically prosper during times of revival since these times produce an interest in Bible study and biblical teaching. Because the overall evangelical church in America has lost its biblical focus the emphasis has shifted to preoccupation with issues that the world thinks are important. Premillennialism

and the fact that Christ could come at any-moment via the rapture of the Church helped keep a believer’s focus on the future. When believers are future oriented it does not lead to inactivity, as many insist, instead when properly applied it motivates believers to get their priorities straight, which is evangelism, discipleship, and worldwide missions. A focus on premillennialism as a fundamental of our faith in the IFCA has been and still remains a powerful truth and motive to live sacrificially in the present because of the future. Maranatha!

Notes

1 George M. Marsden, Understanding Fundamentalism and Evangelicalism (Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1991), 39.

2 David 0. Beale, In Pursuit of Purity: American Fundamentalism Since 1850 (Greenville, SC: Unusual Publications, 1986), 5.

3 Timothy P. Weber, Living in the Shadow of the Second Coming: American Premillennialism 18751982 (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1983), 26.

4 George M. Marsden, Fundamentalism and American Culture: The Shaping of Twentieth-Century Evangelicalism: 1870-1925 (Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 1980), 46.

5 Ibid., 46.

6 Ibid., 117.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid., 138.

9 Yaakov Ariel, On Behalf of Israel: American Fundamentalist Attitudes Toward Jews, Judaism, and Zionism, 1865-1945 (Brooklyn, NY: Carlson Publishing, 1991), 43.

10 Ernest R. Sandeen, The Roots of Fundamentalism: British and American Millenarianism, 1800-1930 (Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1970), 235.

11 Ibid., 37.

12 See Larry Eskridge, God’s Forever Family: The Jesus People Movement in America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013) for an overview of that revival.

Thomas Ice is Executive Director of The Pre-Trib Research Center and Professor of Bible and Theology at Calvary University in Kansas City, Missouri. The PTRC was founded in 1994 by Ice with Dr. Tim LaHaye to research, teach, and defend the pretribulational rapture and related Bible prophecy doctrines. Ice has authored and co-authored about 35 books, written hundreds of articles, and is a frequent speaker at churches and conferences. He has served as a pastor for 17 years. Dr. Ice has a BA from Howard Payne University, a Th.M. from Dallas Theological Seminary, a Ph.D. from Tyndale Theological Seminary and done doctoral studies at the University Wales in Lampeter. He lives with his wife Janice in Lee’s Summit, Missouri and they have three grown sons and seven grandchildren.

- 212 views

Thomas Ice is at the forefront when it comes to defending Premillennialism and particularly the Pretribulational rapture. He is one sharp cookie.

I think a fellowship or church can decide that they value premillennialism enough to make it a necessary belief to their church/group, but to label it a “fundamental” is questionable. It might be better to say that, in time, it became looked upon as a fundamental — for better or worse.

As a confirmed, adamant Premillennialist, I don’t think I would join a church that held another position, but I would not consider such a church neo-evangelical because of this.

I do agree that taking the Bible more literally leads to Premillennialsm (Acts 1:6, Acts 3:19-21 e.g.), but I know a host of people would challenge that. We all have to make a judgment call as to what is obvious in Scripture, while acknowledging that others who are seeking the true meaning of Scripture may disagree with us.

I do think his points that the clarity of Scripture and interest in Bible study birthed the emphasis on Premillennialism, which is a populist belief. The argument that top scholars are amil makes the point. The net effect of a retreat from premil — except for the brainier type — is that many believers no longer give a care about eschatology. I mean, what point is there in studying Ezekiel’s temple if what it says doesn’t really mean anything?

We are returning to a Romish approach, where we let the scholars tell us what to believe because the Bible is too complicated for laymen. Dispensationalism provided a system that make the Bible more intelligible to the dedicated layman.

I appreciate Ice’s different twist on things, especially the clarity of Scripture.

"The Midrash Detective"

Ed commented how premill is a populist belief. Realizing that I’m straw-manning his point, I’m most definitely not a top scholar, nor a scholar, really, at all. But I am amill. In fact, after becoming a Christian, after having been raised in a dispensationalist family, church pastored by my dispensationalist father, and Christian school that taught, at the least, that pre-trib/premill is the only viable position Christians can take, I struggled with reading and studying the Bible. To be clear, I didn’t struggle, necessarily, with the act of reading and studying; I struggled with the hermeneutic I had been steeped in rubbing my understanding of literary analysis raw. It was only after I began learning covenant theology that the Bible began to open up to me in vibrant, deep ways. Frankly, having the bulk of my professional training in storytelling/literary analysis and having spent much of my professional adult life as a storyteller and teaching various aspects of literary analysis, I find dispensationalism convoluted and damaging to a literal understanding of the text. This is also why I tend to squint my eyes, wrinkle my brow, and say, “hmmm” whenever I read or hear anything that charges my hermeneutic with being less literal. I would argue that dispensationalists conflate synonym with literal. In other words, contradicting the author of this article, I don’t believe that premill “speaks to the clearness of Scripture.” I believe it does the opposite.

Ice has kind of a two-part thesis here: a) premil became a nonnegotiable in the fundamentalist movement, b) it should continue to be. I think a. is true of what eventually became majority fundamentalism. But you still have, the World Christian Fundamentals Association and eventually the American Council of Christian Churches, neither of which was ever overtly premil. ACCC’s doctrinal statement here.

So, there was always a component of the movement, however small and quiet, that didn’t want that to be a point of division.

I agree with Ice that essentially literal hermeneutics provides a stronger basis for defense of the faith and defense of Scripture. The continuing faithfulness to the fundamentals of the faith by so many Presbyterians is strong evidence that you can stay faithful without it. The whole phenomenon of confessional Christianity is a bit overlooked.

So, in short, my view is that premil is good, and essentially literal hermeneutics is necessary, but these shouldn’t be a basis for identifying people as outside the true Christian faith. Outside the fundamentalist movement? That’s a better claim, but still not air tight.

Anyway, my take on the fundamentalist movement is that it’s basically now American evangelical history. The landscape has changed and what we have now is the need to find ways to take the spirit of the movement to the present and future: we have some of the same old battles but lots of new ones, and faithful believers need new alliances and new separations, as far as individuals and institutions goes.

Views expressed are always my own and not my employer's, my church's, my family's, my neighbors', or my pets'. The house plants have authorized me to speak for them, however, and they always agree with me.

I find it interesting that the stand was taken on an issue (pre-mil) vs. the fundamental (no pun intended) principle itself which is really what the issue should be. The issue isn’t about eschatology, the issue is defining how to read, interpret, and understand scripture.

My guess is they went that route because it is easier to understand a black and white issue than trying to explain how to properly read and understand scripture. Clearly those who are a-mil or pan-mil approach understanding scripture differently from those who are pre-trib/pre-mil, and the different approaches can lead to many differences in doctrinal conclusions, not just eschatological ones.

Ashamed of Jesus! of that Friend On whom for heaven my hopes depend! It must not be! be this my shame, That I no more revere His name. -Joseph Grigg (1720-1768)

John, I’d love to hear more about what you mean by having your literary senses rubbed raw by the hermeneutic. I personally struggle with the distinctions of literal vs. literary understanding, and you might have a touch of a “Rosetta Stone” in this regard for many of us.

Aspiring to be a stick in the mud.

I’ve sat down several times over the last few years and began writing about why I am not a dispensationalist, especially from the standpoint of my training in literary analysis, understanding, and experience. Obviously, I have yet to actually write anything. Frankly, I made my comment above as a type of fishing exercise; I’m curious as to how my dispensationalist brothers and sisters in Christ respond to what I wrote. I also responded so that at least one dissenting voice can be heard during conversation about the article posted above - an article I found interesting, by the way.

In short (very short), to begin answering your question, Bert, for me it boiled down to is the Bible a unified Story or not. If it is, and I believe with every ounce of my being that is, then a dispensational hermeneutic damages the unity. It inserts chaos and confusion into a Story that is beautiful in its symmetry in ways that the best of all other stories can barely dream to aspire to, and, in doing so, creates two super-objectives for the protagonist (God). At times, those two super-objectives are in conflict with each other. This is why theologians recognize that the most pertinent “boots-on-the-ground” question that divides dispensationalists from CT’s isn’t about eschatology but in reference to Israel and the Church.

No doubt, if any care to respond, dispensationalists will have much good to say that pokes holes in my previous paragraph. If that happens, I will be most appreciative. Just be aware that my final response may end up being in the form of a 5,000+ word article that I won’t finish anytime soon (that’s not to say that I’m already bowing out of this comment thread, because I’m not).

I find it ironic that among those who propose “continuity,” these very people abandon God’s continuity with national Israel. I am a PD, and not among those who advocates segmenting Scripture. There are two major themes in Scripture,IMO, the scarlet thread of redemption and God’s faithfulness ot Israel no matter how badly Israel treats God.

"The Midrash Detective"

There is nothing wrong with accepting a division between Israel and the church. God himself divided Israel from non-Israelites, and even did so post-ascention ever time he references Jews and Greeks (Romans 1:16 and every other time Paul refers to Jews and non-Jews in the same context). This obvious, natural division in scripture does not at all negate the overall theme of Redemption.

Ashamed of Jesus! of that Friend On whom for heaven my hopes depend! It must not be! be this my shame, That I no more revere His name. -Joseph Grigg (1720-1768)

Bert, for me it boiled down to is the Bible a unified Story or not. If it is, and I believe with every ounce of my being that is, then a dispensational hermeneutic damages the unity. It inserts chaos and confusion into a Story that is beautiful in its symmetry in ways that the best of all other stories can barely dream to aspire to, and, in doing so, creates two super-objectives for the protagonist (God). At times, those two super-objectives are in conflict with each other.

As a DT, I will respond: I think the Bible is a unified story and the dispensational hermeneutic is actually what keeps it together. Without it, the story becomes a jumble of confusing and contradictory ideas. Take, for instance, the Law. A non-dispensational hermeneutic sees a tearing apart of the law (both in terms of its parts and in terms of its blessings and consequences). Such a tearing apart cannot be justified in any way that I can find satisfactory. Or take for instance, the promises. A non-dispensational hermeneutics renders the promises of God unintelligible because (as most non DTs admit), the promises fulfilled are nothing like the promises that were made—either in terms of the participants in them or in terms of the actual promises themselves. This is a major flaw that, again, I can find no satisfactory answer to. So far from being confusing and contradictory, a DT hermeneutic actually clarifies and unifies.

This is why theologians recognize that the most pertinent “boots-on-the-ground” question that divides dispensationalists from CT’s isn’t about eschatology but in reference to Israel and the Church.

Both eschatology and Israel and the Church are secondary issues. The “boots on the ground” question is about hermeneutics: What can a text do?

[JNoël]The issue isn’t about eschatology, the issue is defining how to read, interpret, and understand scripture.

[Larry]Both eschatology and Israel and the Church are secondary issues. The “boots on the ground” question is about hermeneutics: What can a text do?

And both sides have done it.

This all comes down to one thing - hermeneutic, and it is an area that I still find amazing that Christians cannot agree on. If we cannot agree on how to approach scripture, then what use is scripture beyond the basics of the gospel and redemption?

Mark Snoeberger’s series on hermeneutics was a really good read.

https://sharperiron.org/article/whatever-happened-to-literal-hermeneuti…

Ashamed of Jesus! of that Friend On whom for heaven my hopes depend! It must not be! be this my shame, That I no more revere His name. -Joseph Grigg (1720-1768)

[Ed Vasicek]God’s faithfulness ot Israel no matter how badly Israel treats God.

You could reword this as God’s faithfulness to His people. That is probably a more accurate reflection of the theme, than the limitation of Israel, since not everyone born of Israel received the promise and there are those that were not born of Israel that did receive the promise. The two major themes are redemption and faithfulness only to Israel, we lack the hope.

Interesting article.

I grew up seemingly surrounded by premillennialists. My dad, Joe Brumbelow, and so many preachers and commentators. Robert G. Lee, Hyman Appelman, W. A. Criswell, Warren Wiersbe, Adrian Rogers, Paige Patterson, J. Vernon McGee, Bailey Smith, Jerry Vines, Hershel Ford, Billy Graham, Robert L. Sumner, John R. Rice, Bob Jones, Jimmy Draper, John MacArthur, H. A. Ironside, and a host of others. And, of course, I grew up with the Scofield Bible, New Scofield Bible, Criswell Study Bible, etc.

Southern Baptists do not require premillennialism. But it seems the most conservative, evangelistic preachers are usually premillennial.

David R. Brumbelow

Discussion