Shall the Fundamentalists Win? (Part 1)

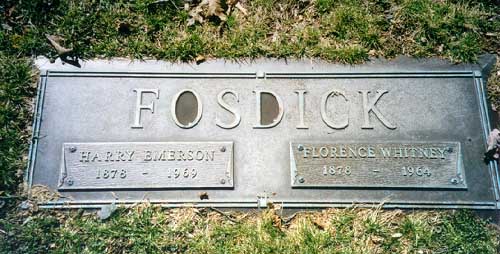

Image

In this landmark 1922 sermon, Harry E. Fosdick, Pastor of First Presbyterian Church in New York, called for an open-minded, “tolerant” view of Christian fellowship. He delivered this address in the midst of the Fundamentalist-Modernist controversy. As is plain from his sermon, he did not want the fundamentalists to win!1

This morning we are to think of the fundamentalist controversy which threatens to divide the American churches as though already they were not sufficiently split and riven. A scene, suggestive for our thought, is depicted in the fifth chapter of the Book of the Acts, where the Jewish leaders hale before them Peter and other of the apostles because they had been preaching Jesus as the Messiah. Moreover, the Jewish leaders propose to slay them, when in opposition Gamaliel speaks “Refrain from these men, and let them alone; for if this counsel or this work be of men, it will be overthrown; but if it is of God ye will not be able to overthrow them; lest haply ye be found even to be fighting against God.” …

Already all of us must have heard about the people who call themselves the Fundamentalists. Their apparent intention is to drive out of the evangelical churches men and women of liberal opinions. I speak of them the more freely because there are no two denominations more affected by them than the Baptist and the Presbyterian. We should not identify the Fundamentalists with the conservatives. All Fundamentalists are conservatives, but not all conservatives are Fundamentalists. The best conservatives can often give lessons to the liberals in true liberality of spirit, but the Fundamentalist program is essentially illiberal and intolerant.

The Fundamentalists see, and they see truly, that in this last generation there have been strange new movements in Christian thought. A great mass of new knowledge has come into man’s possession—new knowledge about the physical universe, its origin, its forces, its laws; new knowledge about human history and in particular about the ways in which the ancient peoples used to think in matters of religion and the methods by which they phrased and explained their spiritual experiences; and new knowledge, also, about other religions and the strangely similar ways in which men’s faiths and religious practices have developed everywhere… .

Now, there are multitudes of reverent Christians who have been unable to keep this new knowledge in one compartment of their minds and the Christian faith in another. They have been sure that all truth comes from the one God and is His revelation. Not, therefore, from irreverence or caprice or destructive zeal but for the sake of intellectual and spiritual integrity, that they might really love the Lord their God, not only with all their heart and soul and strength but with all their mind, they have been trying to see this new knowledge in terms of the Christian faith and to see the Christian faith in terms of this new knowledge.

Doubtless they have made many mistakes. Doubtless there have been among them reckless radicals gifted with intellectual ingenuity but lacking spiritual depth. Yet the enterprise itself seems to them indispensable to the Christian Church. The new knowledge and the old faith cannot be left antagonistic or even disparate, as though a man on Saturday could use one set of regulative ideas for his life and on Sunday could change gear to another altogether. We must be able to think our modern life clear through in Christian terms, and to do that we also must be able to think our Christian faith clear through in modern terms.

There is nothing new about the situation. It has happened again and again in history, as, for example, when the stationary earth suddenly began to move and the universe that had been centered in this planet was centered in the sun around which the planets whirled. Whenever such a situation has arisen, there has been only one way out—the new knowledge and the old faith had to be blended in a new combination. Now, the people in this generation who are trying to do this are the liberals, and the Fundamentalists are out on a campaign to shut against them the doors of the Christian fellowship. Shall they be allowed to succeed?

It is interesting to note where the Fundamentalists are driving in their stakes to mark out the deadline of doctrine around the church, across which no one is to pass except on terms of agreement. They insist that we must all believe in the historicity of certain special miracles, preeminently the virgin birth of our Lord; that we must believe in a special theory of inspiration—that the original documents of the Scripture, which of course we no longer possess, were inerrantly dictated to men a good deal as a man might dictate to a stenographer; that we must believe in a special theory of the Atonement—that the blood of our Lord, shed in a substitutionary death, placates an alienated Deity and makes possible welcome for the returning sinner; and that we must believe in the second coming of our Lord upon the clouds of heaven to set up a millennium here, as the only way in which God can bring history to a worthy denouement. Such are some of the stakes which are being driven to mark a deadline of doctrine around the church.

If a man is a genuine liberal, his primary protest is not against holding these opinions, although he may well protest against their being considered the fundamentals of Christianity. This is a free country and anybody has a right to hold these opinions or any others if he is sincerely convinced of them. The question is—Has anybody a right to deny the Christian name to those who differ with him on such points and to shut against them the doors of the Christian fellowship? The Fundamentalists say that this must be done. In this country and on the foreign field they are trying to do it. They have actually endeavored to put on the statute books of a whole state binding laws against teaching modern biology. If they had their way, within the church, they would set up in Protestantism a doctrinal tribunal more rigid than the pope’s.

In such an hour, delicate and dangerous, when feelings are bound to run high, I plead this morning the cause of magnanimity and liberality and tolerance of spirit. I would, if I could reach their ears, say to the Fundamentalists about the liberals what Gamaliel said to the Jews, “Refrain from these men and let them alone; for if this counsel or this work be of men, it will be everthrown; but if it is of God ye will not be able to overthrow them; lest haply ye be found even to be fighting against God.”

That we may be entirely candid and concrete and may not lose ourselves in any fog of generalities, let us this morning take two or three of these Fundamentalist items and see with reference to them what the situation is in the Christian churches. Too often we preachers have failed to talk frankly enough about the differences of opinion which exist among evangelical Christians, although everybody knows that they are there. Let us face this morning some of the differences of opinion with which somehow we must deal.

We may well begin with the vexed and mooted question of the virgin birth of our Lord. I know people in the Christian churches, ministers, missionaries, laymen, devoted lovers of the Lord and servants of the Gospel, who, alike as they are in their personal devotion to the Master, hold quite different points of view about a matter like the virgin birth. Here, for example, is one point of view that the virgin birth is to be accepted as historical fact; it actually happened; there was no other way for a personality like the Master to come into this world except by a special biological miracle.

That is one point of view, and many are the gracious and beautiful souls who hold it. But side by side with them in the evangelical churches is a group of equally loyal and reverent people who would say that the virgin birth is not to be accepted as an historic fact… . So far from thinking that they have given up anything vital in the New Testament’s attitude toward Jesus, these Christians remember that the two men who contributed most to the Church’s thought of the divine meaning of the Christ were Paul and John, who never even distantly allude to the virgin birth.

Here in the Christian churches are these two groups of people and the question which the Fundamentalists raise is this—Shall one of them throw the other out? Has intolerance any contribution to make to this situation? Will it persuade anybody of anything? Is not the Christian Church large enough to hold within her hospitable fellowship people who differ on points like this and agree to differ until the fuller truth be manifested? The Fundamentalists say not. They say the liberals must go. Well, if the Fundamentalists should succeed, then out of the Christian Church would go some of the best Christian life and consecration of this generation—multitudes of men and women, devout and reverent Christians, who need the church and whom the church needs.

The sermon will continue next week.

Notes

1 The text of the sermon was retrieved from http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/5070/.

Tyler Robbins 2016 v2

Tyler Robbins is a bi-vocational pastor at Sleater Kinney Road Baptist Church, in Olympia WA. He also works in State government. He blogs as the Eccentric Fundamentalist.

- 41 views

Note the calls for “tolerance” and “charity.” It all sounds so polite. So nice. So Christian.

Revisionists are the enemies of the faith. Conservative evangelicals are not. There are many revisionists today, perverting the faith. Yet, some fundamentalists still write articles (for example) advocating separation from a certain young-earth creationist because he’s a “neo-evangelical.” That’s mission drift.

This is the enemy; Fosdick and the modern revisionists who follow his playbook.

Tyler is a pastor in Olympia, WA and works in State government.

Most hymnals include “Faith of our Fathers.” Unless my recollection is skewed, that was written by a Roman Catholic about defending the long tradition of RC faith and doctrine. What do we say about that? At some point, we rightly evaluate by the soundness of the message, and not the identity of the author, right? (Perhaps a legitimate discussion could explore exactly when that point is reached, but I think we all agree that there is such a point which we have all embraced at various times.)

G. N. Barkman

The issue becomes “authorial intent” as I remember Andy Naselli pointing out in his lectures on Keswick theology. There are many songs in our hymnal that could be sung in a different light than they were intended. Personally I just prefer not to sing those but each person has to decide that for themselves.

[josh p]I was pretty surprised that the MacArthur hymnal had a Fosdick song in it. One thing I think conservative evangelicals and fundamentalists could be better at is teaching the history of the movement and especially the fund./modern. controversy.

https://hymnary.org/text/god_of_grace_and_god_of_glory

https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/blogs/kevin-deyoung/a-hymn-worth-not…

Fosdick wrote God of Grace for the dedication of the Rockefeller financed Riverside Church in New York City (October 5, 1930). Years later when he penned his autobiography, Fosdick entitled it “The Living of these Days,” an allusion to a line in the second verse of his famous hymn. When Fosdick wrote of the church’s need for courage and asked God that the church might bloom in “glorious flower,” he had a different vision for the church than we should be comfortable with.

What’s wrong with the words of the hymn? (Maybe I missed something when I just checked JM’s hymnal.)

How many people in your church know who this damnable, apostate Fosdick is?

Should we do doctrinal background checks on all hymn writers?

"Some things are of that nature as to make one's fancy chuckle, while his heart doth ache." John Bunyan

At some point, we rightly evaluate by the soundness of the message, and not the identity of the author, right?

I would think so. There are songs I like and use today even though I don’t approve of the author or group, provided I even know who the author is. The author is really of secondary or even tertiary importance, after the theological content contained in it. The only time I think I’d even worry about that is if the author is current and ensnared in controversy or doctrinal errors (Hillsong, CJ Mahaney, James MacDonald, something like that). I didn’t know that Fosdick was the author of God of Grace and God of Glory, and I am totally OK with using it since Fosdick has been gone for decades now.

I don’t know how it looks or works in your churches, so I’ll ask it here. Does the congregation generally ask for songs to be used or is that a leadership decision?

"Our task today is to tell people — who no longer know what sin is...no longer see themselves as sinners, and no longer have room for these categories — that Christ died for sins of which they do not think they’re guilty." - David Wells

Craig,

Yes I think that is it. Thanks

[Ron Bean]What’s wrong with the words of the hymn? (Maybe I missed something when I just checked JM’s hymnal.)

How many people in your church know who this damnable, apostate Fosdick is?

Should we do doctrinal background checks on all hymn writers?

You might have missed it but I said that I personally would sing songs written by heretics or those with erroneous theology as long as “the lyrics are God honoring.”

I also mentioned “authorial intent” which was meant to distinguish what we mean when we sing a hymn and the way it was intended by the author.

As I said, everyone has to follow their own convictions. My own conviction is that if I know a song means something heretical or seriously erroneous, then I don’t sing it. To me it makes no sense to be scrupulous about proper doctrine from the pulpit but negate it during the singing. This is MY conviction.

I doubt anyone at my church knows who Fosdick is which is why I also said that one thing I think CEs and Fundys could be better at is teaching the history of the Fundy/Modernist controversy.

[Jay]At some point, we rightly evaluate by the soundness of the message, and not the identity of the author, right?

I would think so. There are songs I like and use today even though I don’t approve of the author or group, provided I even know who the author is. The author is really of secondary or even tertiary importance, after the theological content contained in it. The only time I think I’d even worry about that is if the author is current and ensnared in controversy or doctrinal errors (Hillsong, CJ Mahaney, James MacDonald, something like that). I didn’t know that Fosdick was the author of God of Grace and God of Glory, and I am totally OK with using it since Fosdick has been gone for decades now.

I don’t know how it looks or works in your churches, so I’ll ask it here. Does the congregation generally ask for songs to be used or is that a leadership decision?

Jay, in my church it is a leadership or song leader decision. That’s why when we sing certain songs (Keswick stuff, Fosdick, The Old Rugged Cross) I personally do not sing them if the lyrics are not God honoring. I am not out campaigning to avoid them (although I have mentioned one song to the elders). Its just a personal decision.

Are there really people who have been in Fundamentalist or Conservative Evangelical churches for any length of time that do not know who Harry Emerson Fosdick is? What about other famous compromisers and liberals, such as J. C. Massee, Cornelius Woelfkin, or Shailer Matthews?

Most people in Fundamental churches know little to nothing about these men.

G. N. Barkman

I’d never heard of any of these men until I got to undergraduate and had to take a Baptist History class. I’d be surprised if we had ever taught anything like that at my current church.

"Our task today is to tell people — who no longer know what sin is...no longer see themselves as sinners, and no longer have room for these categories — that Christ died for sins of which they do not think they’re guilty." - David Wells

Are there really people who have been in Fundamentalist or Conservative Evangelical churches for any length of time that do not know who Harry Emerson Fosdick is? What about other famous compromisers and liberals, such as J. C. Massee, Cornelius Woelfkin, or Shailer Matthews?

What would be the biblical basis for teaching about these men? Wouldn’t the fact that no one knows who they are indicate that they are not a big threat?

Discussion