"The World's Most Controversial Hymn Book"

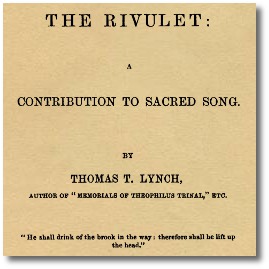

“Dr. Watts’s Hymn-book does not satisfy and suffice me,” said London Congregational minister Thomas Toke Lynch to his Mortimer Street church in 1851 (Memoir of Thomas T. Lynch, p. 95). Three years later, Lynch began penning his own hymns. In November 1855, while minister at Fitzroy Chapel on Grafton Street, Lynch published The Rivulet: A Contribution to Sacred Song also known as Hymns for Heart and Voice. A second edition appeared in 1856 and a third in 1868.

“Dr. Watts’s Hymn-book does not satisfy and suffice me,” said London Congregational minister Thomas Toke Lynch to his Mortimer Street church in 1851 (Memoir of Thomas T. Lynch, p. 95). Three years later, Lynch began penning his own hymns. In November 1855, while minister at Fitzroy Chapel on Grafton Street, Lynch published The Rivulet: A Contribution to Sacred Song also known as Hymns for Heart and Voice. A second edition appeared in 1856 and a third in 1868.

Lynch’s hymns were laden with his own religious interests and poetic expressions and light on doctrine, creed or orthodoxy. In the preface to the second edition, Lynch wrote that his intent was to supplement, not supplant, existing hymnody.

Within two months of the first edition of The Rivulet, conflict broke out among religious newspapers and within the Congregational Union the likes of which has never been seen in any denomination concerning a hymn book. John Campbell, editor of the Congregational Union’s official newspaper, used a newspaper not supported by the Union, titled the British Banner, as a means of criticizing Lynch, his hymns, and those who spoke favorably of them. James Grant, editor of the Morning Advertiser, joined Campbell’s cause. The Nonconformist and Eclectic Review fought back by supporting Lynch and his hymns. By the time “The Controversy”—as it came to be called—ended a year and half later many other periodicals joined the fray. Hundreds of articles and pamphlets had been written in criticism or defense of the hymnal. The bitter debate so engulfed the Congregational Union that the regular autumnal meeting scheduled for September 23, 1856, at Cheltenham, was canceled out of fear that peace could not be maintained.

The immensity of this hymnal controversy prompted English hymn researcher Richard Arnold, of The University of Lethbridge, to title his 2000 essay on the matter “The World’s Most Controversial Hymn-Book: Thomas Toke Lynch and The Rivulet of 1855.”

Criticism of The Rivulet

John Campbell, in the British Banner, pulled no punches after reading The Rivulet. He called Lynch’s hymns “pantheistic,” “unscriptural,” and “unchristian” and accused him of “deliberately contradicting the Word of God…defaming the character of the Son of God…[and] giving lie to the whole teaching of the Spirit of God.” Campbell said they “might have been written by a man who had never seen a Bible, and never heard more than a few words and a few names which might all have been uttered in a moment of time” and that poetically they were “ill-rhymed rubbish” (Memoir, p. 108-110).

James Grant of the Morning Advertiser wrote that The Rivulet “might have been written by a Deist,” contained “not one particle of vital religion or evangelical piety,” and “made no mention of Christ’s divinity, atoning sacrifice, and mediatorial office” (These Hundred Years: A History of the Congregational Union of England and Wales, 1831-1931, p. 222).

The Watchman printed, “We have looked into The Rivulet and cannot conceive how any one can suppose the writer to be an Evangelical Christian” while The Record said “The Rivulet, as a book of hymns, is destitute of all pretensions to poetry” (Memoir, p. 165-166).

Spurgeon, in an article titled “Mine Opinion” that appeared in the May 23, 1856 edition of The Christian Cabinet, wrote that Lynch’s writing style was “fine” but that the content was “useless” either for the sinner or the mature believer because it contained so little doctrine that “one could scarcely guess his doctrinal views at all.” Spurgeon’s article, which also compares Lynch’s hymns in an uncomplimentary way to mermaids and states his belief that they are better suited for Native American worship, is reprinted in his autobiography.

However, attention to the new hymn book was not all negative. Support for Lynch and his hymns came just as quickly and extensively as the criticism.

Defense of The Rivulet

Soon after Lynch’s first edition, the Eclectic Review predicted that the new hymns would become a favorite “in hundreds of musical families” and that they would gradually take “their place among these which have been long consecrated by dear and hallowed associations.” The Nonconformist wrote that Lynch’s hymns “will live and express the joys and aspirations of the devout Christian as long as divine praises are sung in the English tongue” (These Hundred Years, p. 221).

Later, the Eclectic Review printed a protest signed by fifteen well-known London ministers “testifying their respect for [Lynch], and their indignation at the manner in which he had been assailed” (Memoir, p. 108). In response to John Campbell’s criticism, the Nonconformist demanded that he cease his “rude and uncouth despotism.” James Baldwin Brown–one of the fifteen protesters–thought that Lynch was “shamefully and cruelly treated” (These Hundred Years, p. 222-223).

Another supporter of Lynch claimed that “there is no minister in London…who has a firmer belief than Mr. Lynch in the very doctrines which he is charged with denying.” He continued, “it is unsafe at any time to draw sweeping conclusions as to doctrinal belief from the language of poetry. In order to understand a hymn, it is oftentimes necessary to know the writer” (Memoir, p. 147-148).

Lynch himself remained silent for many months while others debated his hymns and the particular doctrines absent from, or apparently skewed by, them.

Lynch’s Response

Eleven months after publishing the first edition of The Rivulet, Lynch began responding to his critics. Under the pseudonym Silent Long, he wrote a book of poetry titled Songs Controversial. Through the fifteen poems in this book, he attempted to demonstrate the folly of his critics and their tactics. Seven of those poems were re-printed in Lynch’s Memoir (p. 111-117). Lynch also wrote a book titled Ethics of Quotation aimed at exposing the unappreciated tactics of his critics.

The following month (exactly one year after the first edition of The Rivulet was published) Lynch addressed his critics directly. According to his Memoir, Lynch said he was “no heretic” (p. 119) and accused his critics of using orthodoxy as “a cloak for transgression” ( p. 120). He denied “their orthodoxy” and charged them with “heresy” (p. 189). Lynch also believed his critics showed “their unfitness for leadership in the Church general,” (p. 199) called them “the dogs of theologic war, in full pack and full cry,” (p. 126) and referred to their newspapers as “the Gog and Magog of the newspaper ‘Evangelicals’ ” (p. 146).

Lynch thought that once “The Controversy” ended, “Men will have more liberty to love one another, notwithstanding differences; and the result will be, that differences will grow less and agreement greater” (p. 173). He believed that the most important question regarded not himself nor his book, but “the liberty which men and churches have in Christ Jesus” ( p. 186).

The Result

Along with the hundreds of articles and pamphlets that emerged during the Rivulet controversy came the publication of Who is Right, and Who Wrong? in 1857.

This book reproduced correspondence between Thomas Binney, who was one of the original fifteen protestors, and James Grant, editor of the Morning Advertiser, regarding theological disagreements that had arisen over The Rivulet. However, theological debate brought no resolution and threatened to destroy the Congregational Union.

Binney, in an effort to save the Union, had proposed in 1856 that the solution to “The Controversy” was for the Congregational Union to not have an official newspaper so that it would have no official ties with John Campbell–Lynch’s most ardent critic. In May 1857, the Congregational Union acted upon Binney’s resolution and decided it would no longer oversee or financially support any newspaper. In the fall of 1857, the autumnal meeting at Cheltenham (which was supposed to have taken place a year earlier) was held amidst peace and calm. The spring 1858 Committee Report stated “Henceforth the magazines are completely detached from…the Congregational Union” (These Hundred Years, p. 234).

Controversy over “the world’s most controversial hymn-book” thus ended, not because the propriety of Lynch’s hymns had been either established or discredited, but because John Campbell was no longer a Congregational Union newspaper editor and because the Union never officially endorsed the new hymn book. When the Union unveiled an approved hymn book in 1859, it did not contain any of Lynch’s hymns. However, this exclusion was in response to the recent animosity generated by the hymns rather than in judgment of their content.

As of June, 2011, the texts for ten of Lynch’s hymns are available at The Cyber Hymnal (http://www.hymntime.com/tch/bio/l/y/n/lynch_tt.htm). Because only a handful of his hymns have survived the passage of time, we may be tempted to conclude that Lynch and his hymns had little, if any, influence upon hymnody in general. However, a hymn writer’s actual texts may wane and fall into disuse while his methods wax and come into common use.

Thomas Toke Lynch published hymns for congregational use that were devoid of doctrine derived or quoted from Scripture and full of the personal religious experiences, natural observations, and spiritual imaginations that came from his “heart.” He deemed these worthy for others to use “for worship” (Memoir, p. 133, 186). Richard Arnold, in the abstract to his 2000 essay, claimed that Lynch’s hymn book “in essence changed the direction of hymnody forever, laying the literary groundwork for modern and even postmodern hymnody.”

Brenda T Bio

Brenda Thomas received her BS from Faith Baptist Bible College (Ankeny, Iowa), MA from Faith Baptist Theological Seminary and MA from California State University Dominguez Hills. She lives near Minneapolis, Minnesota with her husband and two children and is a member of a Baptist church there.

- 124 views

Discussion