Book Review: Schulz and Peanuts

Note: This article is reprinted with permission from As I See It, a monthly electronic magazine compiled and edited by Doug Kutilek. AISI is sent free to all who request it by writing to the editor at dkutilek@juno.com.

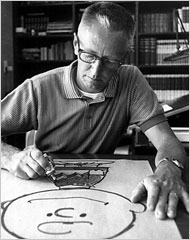

Schulz and Peanuts: A Biography by David Michaelis. New York: Harper, 2007. 655 pp., hardback. $34.95 As a rather typical baby boomer/adolescent of the 1960s, I was an enthusiastic reader of the daily four-panel comic strip “Peanuts,” conceived and drawn by Charles Schulz. I imbibed much of the wit and sarcasm of the strip and made it my own (to my occasional detriment). I was entirely at home with the ever-lonely perpetual fall guy and loser Charlie Brown; his very strange dog, Snoopy; the domineering and often-crabby Lucy; the philosophical and thoughtful Linus (my personal favorite); and the rest of the regular gang. At various times and in various guises, these characters were Schulz’s alter egos or real life “adversaries” caricatured. Michaelis has written a detailed and thorough biography of Schulz, the retiring and reticent barber’s son from the Minnesota Twin Cities. His lifelong aspiration, even from smallest childhood, was to be a cartoonist. By doing so, he achieved worldwide fame and remarkable wealth. (Right: Charles Schulz, Associated Press)

As a rather typical baby boomer/adolescent of the 1960s, I was an enthusiastic reader of the daily four-panel comic strip “Peanuts,” conceived and drawn by Charles Schulz. I imbibed much of the wit and sarcasm of the strip and made it my own (to my occasional detriment). I was entirely at home with the ever-lonely perpetual fall guy and loser Charlie Brown; his very strange dog, Snoopy; the domineering and often-crabby Lucy; the philosophical and thoughtful Linus (my personal favorite); and the rest of the regular gang. At various times and in various guises, these characters were Schulz’s alter egos or real life “adversaries” caricatured. Michaelis has written a detailed and thorough biography of Schulz, the retiring and reticent barber’s son from the Minnesota Twin Cities. His lifelong aspiration, even from smallest childhood, was to be a cartoonist. By doing so, he achieved worldwide fame and remarkable wealth. (Right: Charles Schulz, Associated Press)

Schulz (1923-2000) grew up in an emotionally undemonstrative family. An only child, he was reclusive and reserved from childhood. He was in marked contrast to his country cousins who were loud, brusque, and verbally bellicose—all the things “Sparky” (for such was his nickname) was not. His reserved nature made the frequent Sunday visits with extended family painful and exceptionally uncomfortable for him. His father, like Charlie Brown’s, was a neighborhood barber of modest ambitions.

After high school and service in World War II (during which war his mother died from cancer after four agonizing years), Sparky pursued a career in art and cartooning and finally broke in in 1950 when his local “Li’l Folks” strip went “national” (with seven original subscribing newspapers; “Peanuts” would eventually appear in more than 1,000 papers). Due to a copyright dispute with a defunct comic strip from the 1930s, the name was changed by the national syndicator—against Schulz’s wishes—to “Peanuts,” a name lifted straight from the successful “Howdy Doody” television program’s famous “Peanut gallery” where the live children’s audience sat. Schulz frankly hated the new name (though I $uppo$e he eventually got u$ed to it); for years, people would ask, “Which one of the characters is named ‘Peanuts’?” Many thought it was the dog (my original impression). The strip developed, was picked up by more papers, and by 1955 had become popular nationwide.

Even when fame and considerable fortune came his way because of “Peanuts,” Schulz remained reclusive—indeed, perhaps more so—and used the strip as both a creative outlet and an escape from the real world. In the strip and only there, he had complete control over his “world.” Schulz was personally very much self-absorbed and had a strong aversion to taking responsibility if it could be avoided by losing himself in the strip.

Raised in a quiet, nonreligious home, Schulz somehow never smoked, used profanity, or drank alcohol beyond the rarest and barest exception. Both he and his father came into contact with a small Church of God (Anderson, IN) congregation at the time of his mother’s death. The minister of the small congregation—because of the unavailability of the Lutheran minister—consoled the family and conducted the funeral. After the war, Schulz attended this small church, made numerous friends, became a regular part of the congregation, and eventually made a credible profession of faith in Christ, followed by baptism. While residing in Minnesota, he regularly attended this church—all weekly services—and tithed. His growing income from “Peanuts” eventually accounted for more than half of the church’s total income.

Though often interested in girls during his high school, military, and postwar years, Schulz was with rare exception too self-conscious, too insecure, too introverted, and too fearful of rejection even to speak to girls he found attractive, much less to ask them for a date. In 1951, however, he met and married the sister of a coworker, a 20-year-old divorcee, who at 19 had worked one summer in a New Mexico dude ranch. She met and married a ranch wrangler twice her age, bore a child, and was abandoned by the man—all in short order. Joyce Schulz was strong-willed, domineering, and highly energetic. A driven woman, she was never much of a churchgoer (rarely accompanying Sparky to church in Minnesota) and never any kind of professing Christian. This latter characteristic would eventually have a highly detrimental impact on Schulz’s spiritual life.

At Joyce’s insistence, the new family soon moved to Colorado, where they knew no one and were far from relatives; they remained there less than a year and were soon back in Minnesota (cartoonists can live anywhere while plying their trade). After a few years and numerous kids, Joyce engineered a move to Northern California, where Schulz would reside for the rest of his life. With the move to California, nearly all of Schulz’s regular association with churches ended (he briefly taught—or rather, supervised—a Sunday Bible class in a Methodist Church). And while he continued to read the Bible and commentaries (chiefly the modernist Abingdon Bible Commentary, which could only have served to undermine any conservative faith Schulz had), he never taught anything about the Bible to his children, not even explaining to them the meaning of the Christmas story. They grew up wondering what the nativity scene that decorated the house each December represented. One daughter eventually became a Mormon.

Sparky’s emotionally undemonstrative nature, passivity, aloofness, and escapism led to growing conflict with extroverted Joyce. After a total of five children and more than 22 years of marriage, they divorced in 1973. Before the split, Schulz had an 18-month adulterous relationship with a 24-year-old single woman. “Peanuts” had given Schulz fame, a multitude of fans, immense wealth, and worldwide recognition. But these could not make him a happy man.

As Schulz got away from church, the Bible, and God, his life drifted. In the 1950s and 1960s, as he first became widely known, he was lionized as a model evangelical Christian. His 1965 Christmas TV special, “A Charlie Brown Christmas,” was and remains the traditional Christmas TV program with the clearest, most straightforward presentation of the gospel. I have watched it 30 times at least and still tear up when Linus takes center stage (“Lights, please”) and recites Luke 2. But with an unbelieving wife and without the continuing influence of fellow believers and the Bible in his life, Schulz in essence abandoned the faith. By the end of his life, he was espousing some strange, even heretical theology. He denied that God wants to be worshiped and taught universalism (people with guilty consciences and unforgiven sin self-servingly often hope there is no condemnation for sin, especially their own).

After his tryst with the 24-year-old and while his marriage to Joyce was unraveling to its dissolution, Schulz began a relationship with a 33-year-old married mother of two. After his divorce—and hers—they wed and stayed together until Schulz’s death on February 12, 2000 (the same weekend Dallas Cowboys football coach Tom Landry died).

For years, I had heard reports and rumors of Schulz’s evangelical Christian profession and his turning away from Christianity in his later years, but I had a Pollyannaish, naive perspective on the whole subject until reading this book. My delusions were certainly dispelled. While still recalling with appreciation the humor and entertainment derived over the years from “Peanuts” (especially in the 1960s), I have lost nearly the whole of any respect I might have had for Schulz the man. He was a success as a cartoonist, but a failure as a Christian, a husband, and a father.

Doug Kutilek is editor of www.kjvonly.org, a website dedicated to exposing and refuting the many errors of KJVOism, and has been researching and writing about Bible texts and versions for more than 35 years. He has a B.A. in Bible from Baptist Bible College (Springfield, MO), an M.A. in Hebrew Bible from Hebrew Union College (Cincinnati), and a Th.M. in Bible exposition from Central Baptist Theological Seminary (Plymouth, MN). A professor in several Bible institutes, college, graduate schools, and seminaries, he edits a monthly cyber-journal, As I See It. The father of four grown children and four granddaughters, he and his wife, Naomi, live near Wichita, Kansas. Doug Kutilek is editor of www.kjvonly.org, a website dedicated to exposing and refuting the many errors of KJVOism, and has been researching and writing about Bible texts and versions for more than 35 years. He has a B.A. in Bible from Baptist Bible College (Springfield, MO), an M.A. in Hebrew Bible from Hebrew Union College (Cincinnati), and a Th.M. in Bible exposition from Central Baptist Theological Seminary (Plymouth, MN). A professor in several Bible institutes, college, graduate schools, and seminaries, he edits a monthly cyber-journal, As I See It. The father of four grown children and four granddaughters, he and his wife, Naomi, live near Wichita, Kansas. |

- 1 view

Discussion