Book Review: My Grandfather's Son

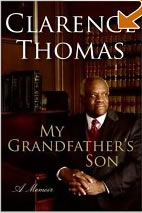

Note: This article is reprinted with permission from As I See It, a monthly electronic magazine compiled and edited by Doug Kutilek. AISI is sent free to all who request it by writing to the editor at [email protected]. My Grandfather’s Son: A Memoir by Clarence Thomas. New York: Harper, 2007. Hardback, 304 pages. $26.95

My Grandfather’s Son: A Memoir by Clarence Thomas. New York: Harper, 2007. Hardback, 304 pages. $26.95 His Honor Clarence Thomas is of course an associate justice of the United States Supreme Court, where he has served since his confirmation in 1991. The confirmation process was infamous for the unbridled viciousness of the attacks on appointee Thomas by the Democrat-controlled Senate Judiciary Committee. In his years on the court, Thomas has always demonstrated a strong commitment to judicial restraint and “original intent” in interpreting the Constitution, rather than “legislating from the bench” as has been the general trend of the judiciary in the past half century. As a consequence, he has often been in the judicial minority of the court (though historically dead-on right), along with the late William Rehnquist, Anton Scalia, and Byron White. But this book is not about Thomas’s years as associate justice. It is a tradition among Supreme Court justices not to write about any other current or living Supreme Court justices or to report on the current doings of the court.

His Honor Clarence Thomas is of course an associate justice of the United States Supreme Court, where he has served since his confirmation in 1991. The confirmation process was infamous for the unbridled viciousness of the attacks on appointee Thomas by the Democrat-controlled Senate Judiciary Committee. In his years on the court, Thomas has always demonstrated a strong commitment to judicial restraint and “original intent” in interpreting the Constitution, rather than “legislating from the bench” as has been the general trend of the judiciary in the past half century. As a consequence, he has often been in the judicial minority of the court (though historically dead-on right), along with the late William Rehnquist, Anton Scalia, and Byron White. But this book is not about Thomas’s years as associate justice. It is a tradition among Supreme Court justices not to write about any other current or living Supreme Court justices or to report on the current doings of the court.

Clarence Thomas, only the second justice of African heritage to serve on the court, would seem to be the most unlikely person to rise to such a position of authority and honor. He was born in 1948 into rural poverty near Savannah, Georgia. His father abandoned the family, and his single mother was incapable of raising two grade-school sons. Therefore, Thomas and his younger brother, Myers, were taken in by their maternal grandfather, whom they called “Daddy,” and their step-grandmother, know as Aunt Tina (pronounced “Teenie”). While the family was short on life’s comforts (though a huge step up from the squalid apartments the boys had lived in with their mother), they were well-fed and well-disciplined. Though only semiliterate, Daddy worked for himself delivering heating oil and farmed a small patch of land during the summers. Daddy’s firm hand and his demand that they pull their own weight and do their own share of the work at home and on the farm kept the boys out of trouble. Daddy never showed the boys much affection, but he did set them a good example.

Daddy, unlike nearly the whole of his relations, converted from Baptist to Catholic chiefly because of the shallow bombast and lack of substance that characterized the black Baptist preachers he knew. This change led him to send the boys to Catholic school, where they were strictly disciplined and compelled to study much (Thomas had four years of Latin before heading to college), which prepared him to succeed in later academic endeavors. In his mid-teens, Thomas had an inclination to become a Catholic priest, undertook studies in high school toward that goal, and went off to seminary in northwest Missouri. But after a year there, he realized (in part because of the racism, prejudice, and hypocrisy he experienced there) that the priesthood wasn’t for him; in fact, he would soon break—for more than a decade—any consistent or formal relationship with any church (a break repaired in the 1980s). He experienced a strained relationship with Daddy over “quitting,” which to Daddy was about the worst offense a person could commit.

After graduating from Holy Cross College, where he was involved for a time in radical campus politics and demonstrations (it was the mid-60s), Thomas secured a law degree from Yale, thinking that it would be his open door to success. It wasn’t. Saddled with huge school debts, he struggled for many years to pay them off while trying to support a wife, whom he met at Holy Cross, and a son. That first marriage ended with his leaving his wife in the early 1980s. (Thomas is rather coy about explaining the circumstances and causes, though he confesses to feeling deep and continuing guilt and regret about this failure.) He soon had custody of his son and raised him to manhood. Thomas remarried in 1987.

During college, law school, and his early years in the workplace, Thomas drank heavily—variously out of rage, boredom, emptiness, and escapism. He gave up drinking completely in 1982.

After law school Thomas worked three years for Missouri Attorney General (later Senator) John Danforth. From there he went to Monsanto Chemical (he hated the work, though it paid well) and then joined Senator Danforth’s congressional staff in Washington. Newly elected President Ronald Reagan appointed him, at age thirty-two, to be assistant secretary for civil rights in the Department of Education. After Thomas’s service there, Reagan appointed him as head of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), a federal agency in disarray. Thomas reorganized it and made it much more efficient and effective. He served in the EEOC until George H. W. Bush appointed him, first as a justice of the Federal District Court for Washington D.C., and then, at only forty-three years of age, as an associate justice of the Supreme Court.

Thomas adopted—or developed—strongly conservative political views during the 1970s and 80s. Daddy had instilled in him a firm belief in personal responsibility, self-reliance, and anti-dependency. He had also taught Clarence not to make excuses for one’s circumstances. Thomas was helped along the way in the development of his thinking by reading the writings of black conservative authors Thomas Sowell (especially) and Walter Williams. Thomas saw that federal paternalism—through welfare, quotas, set-asides and such, however well-intentioned—had the effect of destroying personal responsibility and self-reliance among the black population, guaranteeing the perpetuation of the self-respect-destroying lifestyle of dependence on federal handouts.

When Thomas was appointed to the Supreme Court, liberal Democrats launched the most vicious smear campaign and personal attack on any Supreme Court appointee in history, even worse than what Robert Bork had undergone two years before. It was simply unthinkable to liberals that a black man from the rural South (or anywhere else) could be politically conservative and, revealing more bigotry on their part, could have earned his way to this high office through ability and effort. The capstone of the Senate’s “high-tech lynching” (as Thomas graphically described it on nationally televised TV) was the completely unsubstantiated and unquestionably perjured testimony of Anita Hill, a disgruntled former EEOC staffer. A decade earlier, Thomas had reluctantly hired Hill as a favor to a friend and had repeatedly helped out with various job recommendations after her departure from the EEOC. Her accusations of sexual harassment were expressly contradicted by many witnesses and wholly out of character for Thomas. Yet Ted Kennedy, the crown prince of debauchery and sexual misconduct in Washington, and the other Democrats had the brazen hypocrisy to sit in judgment of Thomas and vote against his confirmation.

In his first sixteen years on the court, Thomas has proven to be one of the finest justices to serve and one who takes his job—and the Constitution as written—seriously.

Doug Kutilek is editor of www.kjvonly.org, a website dedicated to exposing and refuting the many errors of KJVOism, and has been researching and writing about Bible texts and versions for more than 35 years. He has a B.A. in Bible from Baptist Bible College (Springfield, MO), an M.A. in Hebrew Bible from Hebrew Union College (Cincinnati), and a Th.M. in Bible exposition from Central Baptist Theological Seminary (Plymouth, MN). A professor in several Bible institutes, college, graduate schools, and seminaries, he edits a monthly cyber-journal, As I See It. The father of four grown children and four granddaughters, he and his wife, Naomi, live near Wichita, Kansas. Doug Kutilek is editor of www.kjvonly.org, a website dedicated to exposing and refuting the many errors of KJVOism, and has been researching and writing about Bible texts and versions for more than 35 years. He has a B.A. in Bible from Baptist Bible College (Springfield, MO), an M.A. in Hebrew Bible from Hebrew Union College (Cincinnati), and a Th.M. in Bible exposition from Central Baptist Theological Seminary (Plymouth, MN). A professor in several Bible institutes, college, graduate schools, and seminaries, he edits a monthly cyber-journal, As I See It. The father of four grown children and four granddaughters, he and his wife, Naomi, live near Wichita, Kansas. |

- 7 views

Discussion