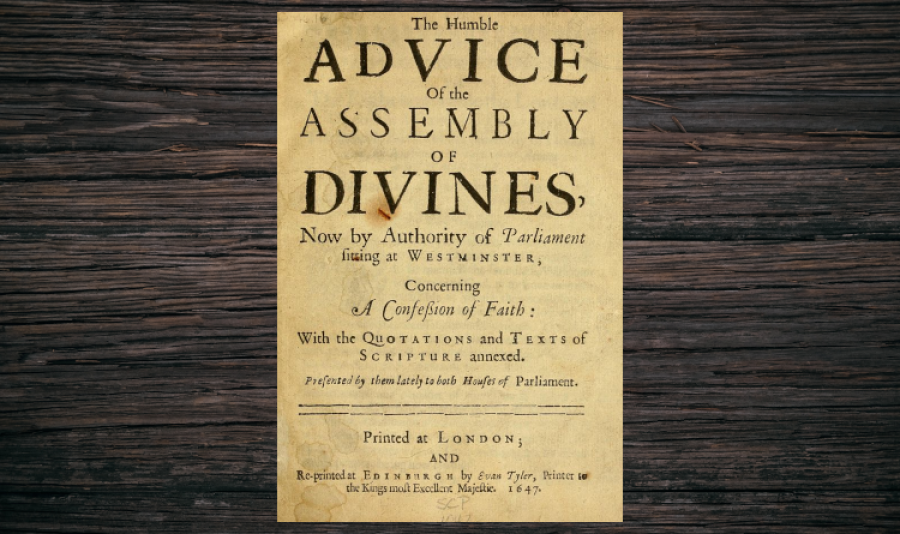

How Shall We Confess the Faith? Strict vs Substantial Subscription (Part 2)

Image

Read Part 1.

Some Problems with Strict Subscription

While I respect the good intentions behind those who advocate this mode of subscription, I believe this mode of subscription is unwise and potentially unhealthy. In particular, I see at least three problems.

Inconsistent

If the church believes the Confession to “assert nothing more or less than the very doctrines of the Word of God,” on what basis can the church allow for exceptions? To change the meaning of even one word or phrase is to alter the doctrine to which that one word or phrase contributes. For example, how can I say, “I affirm the entire Confession to teach nothing more or nothing less than the very doctrines of Scripture” but simultaneously take exception to the Confession’s teaching that the pope (or papacy) is “that [final, eschatological] antichrist”? It seems to me that for strict subscription to be perfectly consistent, it could not allow for any exceptions.20 After all, if the doctrines of the Confession are nothing more or less than the very teaching of Scripture, what warrant could there be for taking exception to said teaching? Furthermore, the only allowable exceptions to the wording of the Confession would entail one’s preference for a certain synonymous word or phrase over another. The moment one substitutes a word or phrase that differs in meaning from the original he has altered the doctrine (be it ever so slightly!). This seems to be a departure from what one professes when he subscribes to the Confession in the language demanded by strict or full subscription.

Unrealistic

Those who advocate strict subscription are careful to affirm the primacy of Scripture and subordinate role of the church’s doctrinal standards. The Bible is infallible and ultimately authoritative. The human creeds (including their own confession) are not infallible, and their teaching is derivatively authoritative, insofar as it agrees with the Bible. Yet at times the advocates of strict subscription speak as if there is or could be a one-to-one correspondence between the teaching and authority of Scripture and the teaching and authority of the church’s doctrinal standards. R. Scott Clark’s solution of “If a confession is not biblical, it should be revised so that it is biblical, or it should be discarded in favor of a confession that is biblical” may sound sensible to some. In my opinion, I think it betrays a lack of realism.

The Westminster Standards and the 1689 Confession, unlike some creeds and doctrinal statements, are fairly lengthy and comprehensive documents. Is it really reasonable to advocate a position that requires one to affirm such an extensive doctrinal statement as fully biblical in its entirety? The fact that we deny the Confession is infallible does not necessitate that all the doctrines of the 1689 Confession are erroneous. Nonetheless, given the length and breadth of the Confession, it is highly probable that there is some part of the Confession—be it ever so small and limited—that is not quite in accord with Scripture.21 Accordingly, I find strict subscription, especially when tied to lengthy and comprehensive doctrinal standards, to be an unrealistic expectation to place upon the subscriber.22

Unhealthy

I do not question the sincerity and conviction of those who advocate an unqualified full subscription yet simultaneously insist that they are not elevating the Confession to the level of Scripture. However, I fear that the practice of an unqualified full subscription may have the very practical consequences that these sincere brothers wish to avoid. It will bind men’s conscience to the Confession in a way that only Scripture itself warrants. Moreover, it will make the Confession practically unamendable and irreformable, which undermines the Reformation principles of sola Scriptura and semper reformanda.

An unqualified full subscription can promote an inordinate and unhealthy view of the Confession relative to the Scripture. The late Dr. John Murray wrote, “It seems to the present writer that to demand acceptance of every proposition in so extensive a series of documents … comes dangerously close to the error of placing human documents on par with Holy Scripture.”23 In other words, our first and primary calling and commitment is to teach the whole counsel of God as taught in Scripture, not necessarily to teach and defend the Confession.24 Murray’s reservations about a strict form of subscription also surface in the reflections of Benjamin B. Warfield. “The most we can expect,” writes Warfield, “and the most we have the right to ask is, that each one may be able to recognize [the Confession] as an expression of the system of truth which he believes.” He continues,

To go beyond this and seek to make each of a large body of signers accept the Confession in all its propositions as the profession of his personal belief, cannot fail to result in serious evils–not least among which are the twin evils that, on the one hand, too strict a subscription overreaches itself and becomes little better than no subscription; and, on the other hand, that it begets a spirit of petty, carping criticism which raises objections to forms of a statement that in other circumstances would not appear objectionable.25

Furthermore, an unqualified full subscription can quench the Spirit’s ongoing work of illumination and, as a result, the church’s ongoing reformation. John Fesko, a professor at Westminster Seminary California, remarks,

If we posses [sic] the very doctrines of Scripture in the Standards, then how is one supposed to disagree or revise ‘the very doctrines of Scripture’?26

That is, one would have to renounce his vow before he could ever entertain the thought that perhaps something he is reading in the Bible does not quite mesh with something taught in his Confession.27

In order to protect the supremacy of Scripture and to keep the church’s doctrinal standards in a position where they are subject to the scrutiny of God’s Word, I suggest some other form of subscription than the version of strict or full subscription described above.

Notes

20 Or as Smith suggests, at least bar men from teaching such exceptions.

21 Scripture is God speaking to man. Theology is human reflection on God’s revelation. Thus, the distinction between Scripture and theology reflects the Creator/creature distinction. Failure to distinguish between the authority of Scripture and the authority of human creeds results in a blurring of the Creator/creature distinction. Of course, we must also affirm the possibility of correspondence between divine revelation and human theology. God’s knowledge is archetypal and our knowledge is echtypal. D. A. Carson illustrates the analogical but not univocal relation of objective truth and subjective interpretation of the truth with the asymptote: “A curved line may approach a straight line asymptotically, never quite touching it but always getting closer…. In precisely the same way, we may not aspire to absolute knowledge of the sort only Omniscience may possess, but the ‘approximation’ may be so good that it is adequate for placing human beings on the moon.” The Gagging of God: Christianity Confronts Pluralism (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1996), 121.

22 The so-called Apostles’ Creed is not nearly as comprehensive as the WCF or 1689. While most Reformed believers can affirm the Apostles’ Creed, a good number would take exception to the phrase that depicts Jesus as descending into hell. At the very least, they’d feel the need to qualify that language.

23 “Creed Subscription in the Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A.” in The Subscription Debate (Greenville, SC: Greenville Presbyterian Theological Seminary, n.d.), 79.

24 Certainly, the Confession may and should serve as a help and a guide in our proclamation and defense of Scripture. As Spurgeon expressed it to his congregation, “This little volume is not issued as an authoritative rule, or code of faith, whereby you are to be fettered, but as an assistance to you in controversy, a confirmation in faith, and a means of edification in righteousness.” Cited in the preface to the Baptist Confession of Faith of 1689 (Carlisle, PA: Grace Baptist Church, n.d.), 8.

25 From his “Presbyterian Churches and the Westminster Confession,” as cited by George W. Knight III in “Subscription to the Westminster Confession of Faith and Catechisms,” 135.

26 “The Legacy of Old School Confession Subscription in the OPC,” Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 46:4 (Dec 2003): 695.

27 John Frame agrees and writes, “[Confessions] could never be amended; anyone who advocated change would automatically be a vow-breaker and subject to discipline.” Doctrine of the Knowledge of God (Phillipsburg: Presbyterian and Reformed, 1987), 308. Similarly, James E. Urish remarks, “Of course, if one took the ‘strict’ full subscriptionist position, one could not teach anything contrary to any articles in the Confession or Catechism. One wonders how the Church could ever perfect these standards with this kind of constraint. It does seem that from the full subscriptionist position there is an implicit assumption that the Westminster Standards fully or satisfactorily summarize the teaching of the Bible and ought not to be amended.” “A Peaceable Plea About Subscription: Toward Avoiding Future Divisions,” in The Practice of Subscription, 223.

Bob Gonzales Bio

Dr. Robert Gonzales (BA, MA, PhD, Bob Jones Univ.) has served as a pastor of four Reformed Baptist congregations and has been the Academic Dean and a professor of Reformed Baptist Seminary (Sacramento, CA) since 2005. He is the author of Where Sin Abounds: the Spread of Sin and the Curse in Genesis with Special Focus on the Patriarchal Narratives (Wipf & Stock, 2010) and has contributed to the Reformed Baptist Theological Review, The Founders Journal, and Westminster Theological Journal.

- 89 views

I believe Robert Gonzales is spot on in his reservations about strict subscription to any confession of faith. I attended a pastors conference about thirty years ago where the organizers proposed amending the London Baptist Confession of Faith to eliminate the statement about the Pope being the Anti-Christ, as well as one or two other minor items. From the reaction of some, one would have thought that the proposal was to eliminate faith in the deity of Christ. Absolutely No alteration of this venerable document must be allowed! The proposal was abandoned.

On the other hand, I have a friend who taught at Southern Baptist Seminary in Louisville, KY, in the late seventies. Faculty were required to sign the school’s statement of faith annually. He told me that his response was something like, “I’ll be glad to sign it, but I think I’m the only one here who actually believes it.” In other words, the entire faculty signed , each with his own personal reservations about the parts which he didn’t “strictly” believe. That’s how liberal faculty were able to teach contrary to their school’s doctrinal statement. That begs the question, “Who decides which statements must be affirmed strictly, and which may be disregarded?”

G. N. Barkman

Speaking as a church, rather than a school, we attempt to deal with the different facets of what is described here in our membership agreement. Members sign that they agree to:

- Submit to the teaching of scripture as expressed in the Statement of Faith

- Be bound by the church covenant

- Be governed by the church constitution

The language “submit to” in the first statement is a recognition that not everyone will agree with every single little point in the Statement of Faith, but they will understand that that is what is taught at our church, and that causing division in the church over points in the SoF will not be tolerated. Prospective members also agree to be bound by the covenant, and governed by the constitution. In all these cases, members might not have 100% “mental assent” to what is written, but we have made it clear that the church operates according to these, whether everyone agrees to every point in them or not, and members are clear what is expected of them. All of this is gone over in more detail in our new members class.

For those who become teachers of any kind, they must further agree to not teach anything contrary to what is in the SoF, again, whether that is their personal position or not.

It may sound like we’ve gone a little overboard with this, but we wanted to make things as clear as we could, and it’s not been an issue in practice. We have members from many different backgrounds, and we understand that everyone is not going to see every little point of the Christian faith in exactly the same way our church sees it. We just make it clear how we are going to operate and what will be taught without forcing someone to personally agree to something they can’t.

Dave Barnhart

That approach seems entirely reasonable to me. I preach at my church every once in a while and the pastor knows that I disagree with certain doctrinal positions of the church. I simply don’t preach those areas. Admittedly, this can be difficult if the disagreement is widespread. I am dispensational and the church is covenantal for example. This certainly limits available passages and I don’t think it would be wise for me to teach something like a Sunday school that has a time for questions. To me, if someone “subscribes” to the essentials of the faith they should be considered believers. That doesn’t mean they should be teaching at the church though. I’ve always thought a two layer doctrinal statement would be a good idea; one for membership and one for elders or even those that are teaching.

[josh p]To me, if someone “subscribes” to the essentials of the faith they should be considered believers.

I certainly don’t disagree with that. We kind of think of levels of belief as concentric circles, each getting smaller. Inside the large circle of believers, there are other circles that represent churches. These would be entirely contained within the big circle, but may only intersect other church circles at less than 100%. Not all true believers in the Gospel would be in sync with every belief of our church, and we often fellowship with believers that are not 100% like we are. However, because our SoF, not to mention the pastor, go into much more detail in sermons, teaching, etc., than the cardinal doctrines required to be a believer, we draw the circle closer for those in our church than simply those who are true Christians. We don’t define those outside our church circle as unbelievers if they still believe the true Gospel, but there may be certain areas in which we would not be able to worship together or coordinate in ministry.

That certainly applies even to the church that owns our building. We rent the facilities and use them for our own services, but for a number of reasons, we could not partner with them in every aspect of ministry, even though they are close enough that both pastors and both churches have no issue with our church using the building and paying the other church.

I’ve always thought a two layer doctrinal statement would be a good idea; one for membership and one for elders or even those that are teaching.

That might actually work in the right circumstance. We’ve just found it easier to have one doctrinal statement (Statement of Faith) that all agree is the position of the church. Elders and teachers have to be careful to follow it when teaching, but with any detailed doctrinal statement, I doubt that there are any two people in the church who would agree exactly on every point 100%.

Similar to you, my background is different from that of many in my church. We are a Bible church, largely baptistic in doctrine, whereas I come from a fundamental Methodist background. Needless to say, I don’t agree in every single point with the SoF, and I was one of those who wrote it! However, the SoF was not simply an expression of my faith, but that of the whole church. It went through a number of revisions before being voted on as part of the constitution. It passed nearly unanimously as the position of the church, and that is what new members agree is the doctrinal statement. We fully expect each new member to have small disagreements, but if there were really large ones, we would most likely tell them that they would be happier in another church.

Dave Barnhart

…with our doctrinal statement, but when a couple applied for membership, with the husband agreeing completely, but the wife having reservations about the doctrine of election, we modified our requirement. Everyone has to complete a detailed study of the Doctrine of Grace as part of the membership process. If they do so successfully, affirm that they understand what we believe and teach, and agree that they will do nothing to oppose or undermine our teaching, we are willing to receive them as members. We have received two or three individuals in this category over the last twenty years without any problems. There are some lovely and godly believers who have “hang-ups” regarding election. If they are willing to be identified with us, we are happy to receive them with the clear understanding stated above.

G. N. Barkman

[G. N. Barkman]Everyone has to complete a detailed study of the Doctrine of Grace as part of the membership process. If they do so successfully, affirm that they understand what we believe and teach, and agree that they will do nothing to oppose or undermine our teaching, we are willing to receive them as members.

That is not all that different from what we do (though we are not a church that makes a Calvinistic position central). Part of our new members class is going over our documents, particularly the Statement of Faith and Covenant, and we make sure that new members understand what we believe and teach, agree to submit to it (which is explained as not opposing or causing division over the official church position), and agree to the other requirements as I posted above. If they meet those requirements (and sign that they do) we are also happy to receive members in that way. We have yet to have anyone try to cause division over the church’s SoF.

Dave Barnhart

Thanks, brothers, for reading and interacting with the posts. Interestingly enough, the Confession itself supports a kind of two-level standard of commitment: one for church officers and one for church members. Officers, we may assume, are expected to know and subscribe to the Confession. Members, however, are required to have a credible profession of faith with no accompanying beliefts or conduct that clearly undermine that profession. Here’s how the Confession puts it:

All persons throughout the world, professing the faith of the gospel and obedience unto God by Christ according unto it, not destroying their own profession by any errors everting the foundation, or unholiness of conversation, are any may be called visible saints; and of such ought all particular congregations to be constituted (2LC 26.2).

Thus, the prerequisite for church membership is, simply, a credible profession of faith that is not contradicted by serious doctrinal error or ungodly behavior. Mastery of the Confession as a requirement for membership is conspicuously absent from the Confession itself.

There are biblical reasons for the two-tiered commitment as well. But I thought I’d simply highlight the language of the Confession itself since there are a few today who seem to believe the church member must offer the same commitment to the church’s doctrinal statement as the church officer.

Discussion