Who is the Word?

Image

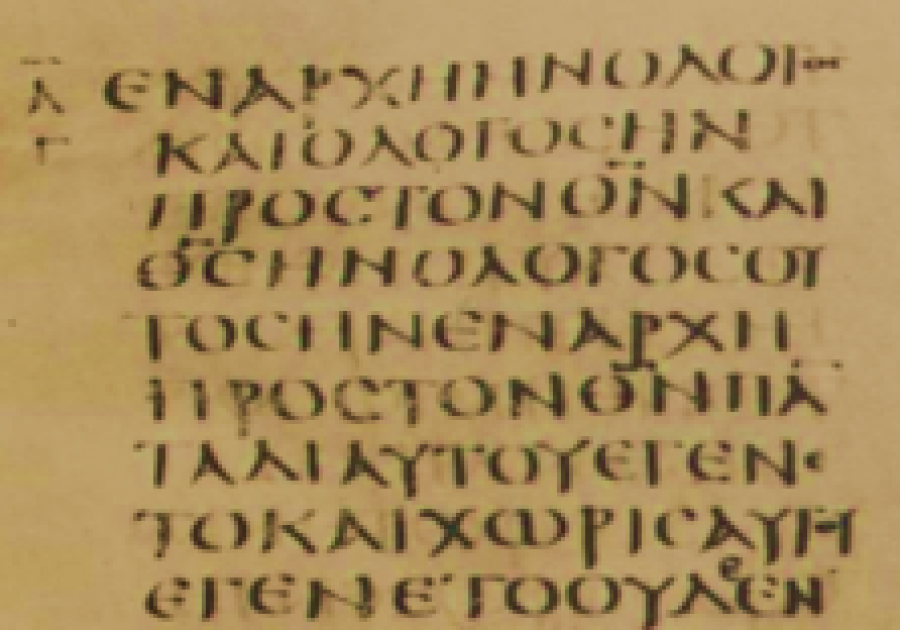

Excerpt from John 1 from manuscript GA 01 (courtesy of CSNTM.org)

The Gospel of John is important. And, in a piece of writing noted for its Christology, the prologue (John 1:1-18) is rightly considered to be a masterpiece. Because it’s so important, it’s attracted any number of critics and false teachers who desperately try to explain why it doesn’t actually say … what it actually says.

An ordinary Christian can go batty pondering all the controversies inherent in this passage. Was John 1:1 (“and the Word was God”) translated correctly? Have Christians been influenced by pagan, Greek philosophy to interpret “the Word” as the co-equal, co-eternal Son of God? These are good questions, and lots of good theologians and bible teachers have lots of good answers for them. But, setting these issues aside for a time, if you take a step back and just consider the content as a literary unit the message is very clear.

Who is the Word?

At1 the very beginning, when the creation happened, the Word was there (Jn 1:1a). So, whoever this Word is, He’s eternal. He’s prior to creation. More than that, the Word is with God (Jn 1:1b). God is before creation, and so is the Word. They’re together. They share the same space; they’re with one another. Even better yet, the Word actually is God (Jn 1:1c).

But, how can this be? How can the Word actually be God? John is saying the Word is somehow distinct from God and there at the beginning with God. Yet, the Word is God, too. What does this mean? It shows us that God and the Word are both eternal, they both stand outside of creation, and they both share the same nature. They’re one, and yet they’re distinct, too.

And, God made everything through the Word (Jn 1:3). The language conveys personal agency, and the Word is the living, active and personal agent who made creation on God’s behalf. “Without Him was not anything made that was made,” (Jn 1:3). Why is that? It’s because “in him was life” (Jn 1:4); that is, the Word contains life and is the source of life and creation. This life is the light which shines the way for men to come to faith; to escape from the figurative darkness of sin and wickedness (Jn 1:4b-5).

The Apostle John then briefly explained the Baptist’s ministry. God sent him to tell people about the Word (note the distinction again). John proclaimed the Word was the light for all men “that all might believe through him,” (Jn 1:7). John himself wasn’t the light, “but came to bear witness about the light,” (Jn 1:8).

The irony, of course, is that the very Creator of creation came into the world, “yet the world did not know him,” (Jn 1:10). He came to His own people, and they rejected Him (Jn 1:11). Notice that it isn’t God who came to His people; it was the Word. Of course, the Word shares the same nature as God so He can properly be said to be God. But, in this prologue, the Word and God are distinguished from one another. John will go on to speak of the Father in contrast to the Son later in the book. For now, however, it’s enough to know John is painting a deliberate contrast between God and the Word.

It’s true people rejected the Word. But, that’s not the end of the story. It all doesn’t end in tragedy and darkness. After all, “[t]he light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it,” (Jn 1:5). In fact, the Apostle hastens to add, to everyone who did receive the Word (that is, who believed in His name; in effect, who He was as the incarnate God-Man), the Word did something very special. He gave these people the right or privilege to become God’s children (Jn 1:12). The Word didn’t give people the power to become His children; He made them God’s children.

People aren’t born into God’s family; they have to be adopted by God. John explains God’s children don’t come to Him by blood relation, or by the sexual desires of a man or woman who produce a child, or even the desires of the husband himself. People don’t become God’s children by physical descent, or by the will of any of his parents. How, then? They’re born from God’s will.

Again, notice the delineation of roles:

- God wills people to become His children

- This will is actuated when they receive the Word by believing on His name; that is, in who He is as the incarnate GodMan.

This is beautiful, and the Apostle tells us how it all came about. The Word “became flesh and dwelt among us,” (Jn 1:14). This is the incarnation, where the Word added a human nature to His divine nature.2 God (i.e. the Father) didn’t become flesh and come here; the Word did. John and the other apostles are eyewitnesses who saw the Word’s glory! What kind of glory was it? It was the glory of the unique, one and only Son who comes from the Father, full of grace and truth (Jn 1:14). In other words, it was the same as the Father’s glory.

Notice that John more precisely defines “God” here as “the Father.” It was His glory that descended on Sinai (Ex 19:16-19), that filled the tabernacle (Ex 40:34-38) and Solomon’s temple (1 Kgs 8:1-11). It was also His glory that left that same temple during the exile (Ezek 8-10), and hasn’t returned since. The Word’s glory is just like that.

This Word is the one who John the Baptist preached about. He told everyone the Word would come on the scene after him, but outranks him. Why does the Word outrank John, a true prophet from God? Because the Word came before John (Jn 1:15). This makes sense, because the Word created Creation according to the Father’s will and only walks the earth because He “became flesh and dwelt among us,” (Jn 1:14).

The Word’s glory, which John and the others saw and marveled at, is full of grace and truth. Why does John say this? Because from His grace all believers continue to receive grace upon grace; that is, an unending flow of graces which pile atop one another (Jn 1:16). What’s so marvelous about this cascade of grace upon grace? Well, the Apostle says, the law came from Moses, but grace and truth came from Jesus Christ (Jn 1:17). Here John stops being coy and explicitly identifies Jesus as the Word.

This is the New Covenant; the new and better way that Jesus inaugurated with His life, death, burial and resurrection. The law of Moses did bring grace and forgiveness to the believer but that atonement wasn’t final and permanent; it was on layaway. The law of Moses did point to the truth of Christ but it didn’t contain that truth; it was a marker along the way. John was obliquely referring to the new and better covenant, which all believers show and tell the world about as they celebrate the Lord’s Supper in local churches.

Nobody has ever seen God. But, the only God who is at the Father’s side has made Him known (Jn 1:18). Once again, John draws a distinction between Father and Son, and identifies Jesus as God once more. Moses is the penultimate Israelite (along with Abraham), but he couldn’t see God. Jesus sits at the Father’s side, and He’s come here to make Him known to us. Moses served his purpose, and even he knew someone else would come from God (Deut 18:15f). That someone is Jesus, the Word who was there before the beginning, who can fully reveal God to sinful men.

The Word is God the Son Incarnate

John’s prologue isn’t hard to understand. But, too many people make it hard (which isn’t at all the same thing) when they refuse to read it as a literary unit, or have a theological agenda, or waste sermons explaining the joys of Colwell’s Rule in John 1:1. The prologue is about Christ, and it tells us He is distinct from the Father, and co-equal and co-eternal with Him. It’s a synopsis of Christ’s identity and ministry. It’s the Apostle’s dustjacket summary of the incarnation:

The Word existed before Creation. The Word made Creation. The Word was with God before Creation, and He’s also God, too. God made everything through the Word, who contains and embodies life itself and acts as a light for all men. That light shined in the darkness, and Satan still hasn’t overcome it.

God sent John the Baptist to tell everyone about the Word, but the world rejected the Word anyway. But, for those few who did receive the Word, who believed in His name, He gave the right to become God’s children. To do all this, the Word took on flesh, dwelt among us, and eyewitnesses saw His glory. His glory was like that of the only Son’s, identical to the Father’s, full of grace and truth. And, the Word pours out grace upon grace to His people; to those who received Him. Moses brought the law, but Jesus brought the new and better covenant characterized by grace and truth.

Nobody has ever seen God, but Jesus (the only God) who sits at the Father’s side has made Him known to all who have ears to hear. He’s better than Moses. He’s Moses’ successor. And, to all who receive Him He gives the privilege to become a child of God, according to God’s will.

All glory to God … and to Jesus, too!

Notes

1 The preposition here (Ἐν ἀρχῇ) is temporal, and the sense is “at the beginning;” that is, at the point in time at which creation began.

2 “Accordingly, while the distinctness of both natures and substances was preserved, and both met in one Person, lowliness was assumed by majesty, weakness by power, mortality by eternity; and, in order to pay the debt of our condition, the inviolable nature was united to the passible, so that as the appropriate remedy for our ills, one and the same ‘Mediator between God and man, the Man Christ Jesus,’ might from one element be capable of dying and also from the other be incapable. Therefore in the entire and perfect nature of very man was born very God, whole in what was his, whole in what was ours,” (Leo the Great, “The Tome of St. Leo,” in Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Second Series, 14 vols., ed. Philip Schaff and Henry Wace, trans. Henry R. Percival (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1900), 14:255.

Tyler Robbins 2016 v2

Tyler Robbins is a bi-vocational pastor at Sleater Kinney Road Baptist Church, in Olympia WA. He also works in State government. He blogs as the Eccentric Fundamentalist.

- 1 view

Discussion