Paul at Athens: Observations for Apologetics

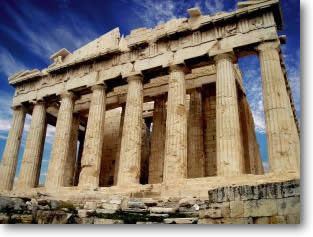

Within the Book of Acts is an anthology of apostolic preaching. Among those sermons is Paul’s address to the pagans and philosophers of Athens, what has been called his Areopagitica. [1] Here Paul proclaimed the gospel, not to  biblically informed, monotheistic Jews, but to pagans and philosophers of thoroughly unbiblical presuppositions. Here if anywhere we would expect to find insights on how to do apologetics today among secularists with their various isms or among modern pagans. Should apologetics be presuppositional, classical, evidential, cumulative case? Where is the point of contact between belief and unbelief? How should the argument be structured?

biblically informed, monotheistic Jews, but to pagans and philosophers of thoroughly unbiblical presuppositions. Here if anywhere we would expect to find insights on how to do apologetics today among secularists with their various isms or among modern pagans. Should apologetics be presuppositional, classical, evidential, cumulative case? Where is the point of contact between belief and unbelief? How should the argument be structured?

Before we attempt a full textbook on apologetics from this single passage, a few preliminary observations are in order. First, the passage obviously summarizes Paul’s message; it does not elaborate on his outline. Second, this preaching like all preaching suits a particular occasion, and some of Paul’s statements may be rhetoric based on details that the passage does not disclose (e.g., audience reactions during the sermon). Third, the message is not so much an argument or back-and-forth debate as a proclamation, Paul answering their question, “What’s this Jesus and resurrection deal all about?” For these reasons and for the basic hermeneutical caution not to make any narrative absolutely normative for today, we should be careful not to decide in favor of any one apologetic methodology based on this one passage alone.

Nevertheless, having been convinced of presuppositional apologetics based on the study of the rest of Scripture, I find Paul’s preaching here entirely consistent with what Scripture says elsewhere; that is, in my estimation, entirely consistent with presuppositionalism.

Paul’s Basic Message Remains the Same

Throughout Acts, the apostles consistently emphasized Jesus’ resurrection. Paul’s preaching in Athens was no different. We are told that in the synagogue with the Jews and proselytes and in the marketplace with whoever would hear, he preached Jesus and the resurrection. This distinct message earned him an invitation to preach it to the Areopagus (Acts 17:18).

And while Paul incorporated quotations from pagan poets for his own purposes, the warp and woof of his speech is still Old Testament language. Let’s reconstruct his speech using only Old Testament quotations: “In six days the Lord made heaven and earth, the sea, and all that in them is” (Ex. 20:11, KJV). “But will God indeed dwell on the earth? behold, the heaven and heaven of heavens cannot contain [God]; how much less this house that I [Solomon] have builded?” (1 Kings 8:27). “If [God] were hungry, [God] would not tell thee: for the world is [God’s], and the fulness thereof” (Ps. 50:12). “He that created the heavens” also “giveth breath unto the people upon it, and spirit to them that walk therein” (Isa. 42:5). “When the most High divided to the nations their inheritance, when he separated the sons of Adam, he set the bounds of the people according to the number of the children of Israel” (Deut. 32:8).

Paul may not have cited chapter and verse, yet this is Bible.

Paul Claims Authority

Paul violated every secular sensibility by claiming authority to speak for God. While the pagans, whose polytheistic shenanigans so vexed Paul, constructed an extra altar to the Unknown God (because, after all, no one could know), Paul stated flatly that he did know. The Stoics have blind fate that moves us all like so many springs and gears in a watch; the Epicureans have their swerving atoms and the remote possibility of gods somewhere out there, made of the same stuff we are but certainly not concerned with our affairs. Stoics trusted their reason, Epicureans their senses. And now Paul showed up and said, “So you say God can’t be known? Actually, I speak for Him. Here’s what He has said and what He’s going to do.” He said, “What therefore you worship as unknown, this I proclaim to you” (Acts 17:23, ESV). And Paul concluded his message with God’s command to repent and a doomsday prophecy (17:30–31).

Instead of laying out the gospel as something to be evaluated based on some other authorities (e.g., reason, experience, first principles), he laid out the gospel as the authoritative message to be obeyed. This is not to say that he rejected reason and experience. Rather, he pulled general revelation into the discussion as something authoritative, sufficient, and clear enough to warrant an imperative. The same God who speaks in Scripture and through Paul also speaks voicelessly through the data of creation and history.

Paul Finds an Imperative in General Revelation

General revelation is not ambiguous data open to interpretations that could go either way. Paul told us this in Romans 1. In general revelation, invisible things are clearly seen with the mind’s eye, that is, understood. God’s general revelation is so authoritative, sufficient, and clear that it renders unbelievers defenseless (“without excuse” is more literally “without an apologetic” [Rom. 1:20]). What we know of our Maker (His transcendence, self-sufficiency, sovereignty), what even the pagan poets write about, makes idolatrous practice positively ludicrous. Therefore, Paul found an imperative: “Forasmuch then as we are the offspring of God, we ought not to think that the Godhead is like unto gold, or silver, or stone, graven by art and man’s device” (Acts 17:29, KJV, emphasis added). God’s sustaining presence is inescapable; we ought not to worship the finite gods of myth.

That God overlooked their ignorance is no excuse. God has left much unpunished since the world began. There will be an accounting. God’s overlooking is “forbearance,” not forgiveness or letting them off due to extenuating circumstances (Rom. 3:25; see also Peter’s discussion of willful ignorance, divine longsuffering, and final judgment in 2 Peter 3).

Paul Preaches Jehovah, Not Monotheism in General

Jehovah God who “inhabits eternity” also dwells “with him who is of a contrite and lowly spirit” (Isa. 57:15, ESV). This is biblical transcendence and immanence. Take away God’s immanence—His personal involvement with the world—and you have not Jehovah minus immanence but something different: deism, Stoicism’s blind fate, possibly the remote gods of Epicureanism. Take away God’s transcendence—His infinity, eternality, immutability, uniqueness—and you have not Jehovah minus transcendence but something different: pantheism, Open Theism, possibly the polytheism of the Pantheon and the Iliad.

To argue for the Unmoved Mover or the Big Major Premise in the Sky is not to argue for the biblical God. But Paul does not talk about a bare First Cause, or an Unmoved Mover, or any other sub-Christian view of God that could be mistaken for Aristotle’s “thought thinking itself.” He offends Athenian sensibilities left and right, preaching God’s transcendence, immanence, and the unique prerogative of Jesus Christ whom God raised from the dead to validate said prerogative. This is not an incremental progression from bare monotheism into Christianity but Christianity start to finish.

God is transcendent in that He made everything, is Lord of everything, needs nothing, but sustains everything and governs civilizations (Acts 17:24–26). He is the very matrix in which we live (17:28). He is immanent in that He is involved in a personal, purposeful way in sustaining and governing mankind and that He wants to be found. And He isn’t far away. (17:26–27). Furthermore, He expects to be listened to and obeyed; He both makes the law and judges lawbreakers (17:30–31). He has done a very particular work in a particular Person, Jesus, by miraculously raising Him from the dead, demonstrating divine approval of Jesus’ appointment to be Judge of all the world. This is very different from myth, from impersonal absolutes, from personal but finite deities. This is biblical religion with an absolute personal God and an essential historical component that could be verified by eyewitnesses.

Paul’s Point of Contact Underscores an Antithesis

Finally, the point that is possibly most under contention among different schools of apologetics. How did Paul go about establishing a connection with the Athenians? Did he compliment their religiosity to curry favor? Did he compliment their religiosity because at least it’s a step in the right direction for them? Or did he do something else?

The Greek word that the Authorized Version translates “too superstitious” and the English Standard Version “very religious” is ambiguous enough to yield both translations. Perhaps, then, we are watching Paul’s calculated ambiguity. He paid the Athenians a “compliment” but not really. However, he did nothing to commend their altar to the Unknown God. If anything, he pounced on their self-admitted ignorance.

Some would see the natural man as wanting basically all the right things, except he’s looking in all the wrong places. Or there are those like Chesterton who view pagan religion and mythology as the groping of men without special revelation, or the best the natural man can do. However, idolatry vexed Paul, and he hardly gave the Athenians a pat on the back for being conscientious and not omitting any god. Paul basically told the Athenians the opposite of everything they thought: their god was unknown, but His God spoke through him and is inescapable in general revelation; their gods were either uninvolved or involved in the world in ways more akin to a soap opera than to a religion; their gods had dubious morality, but Jesus Christ judges righteously; the Athenians thought they had done their part by worshiping an unknown God, but the true God blamed them for not worshiping Himself, the God they could have known if only they’d really felt around a little.

Some may present Paul as building on common ground, that is, the religious impulse. But Paul singled out the acknowledged defect in their religious system and, as with a piece of cloth already snipped, began his tear from there.

Conclusion

From this passage, I infer that Paul and his argument are both fully submitted to the lordship of Jesus Christ. His reasoning is governed by Scripture, and any data he used got pulled into this overall biblical framework of thought. He did not seek to establish his message on some other grounds. And his point of contact, instead of being some common epistemology, is a mockery of their self-professed ignorance that leads to ridiculous superstition. To attack worldly religion and philosophy and to offer Christianity as the clear alternative, indeed the only possibility, is presuppositional apologetics. It seems that this is more or less what Paul did.

___________

1. From Areopagus, also known as Hill of Ares or Mars’ Hill, the word Areopagus here more likely applies to the assembly that met there or elsewhere. The precise location of Paul’s sermon is immaterial; the passage makes the audience demographic, which has far more bearing on the discussion, clear enough.

Mike Osborne received a B.A. in Bible and an M.A. in Church History from Bob Jones University. He co-authored the teacher’s editions of two BJU Press high school Bible comparative religions textbooks What Is Truth? and Who Is This Jesus?; and contributed essays to the appendix of The Dark Side of the Internet. He lives with his wife, Becky, and his infant daughter, Felicity, in Omaha, Nebraska, where they are active members at Good Shepherd Baptist Church. Mike plans to pursue a further degree in apologetics. Mike Osborne received a B.A. in Bible and an M.A. in Church History from Bob Jones University. He co-authored the teacher’s editions of two BJU Press high school Bible comparative religions textbooks What Is Truth? and Who Is This Jesus?; and contributed essays to the appendix of The Dark Side of the Internet. He lives with his wife, Becky, and his infant daughter, Felicity, in Omaha, Nebraska, where they are active members at Good Shepherd Baptist Church. Mike plans to pursue a further degree in apologetics. |

- 78 views

Discussion