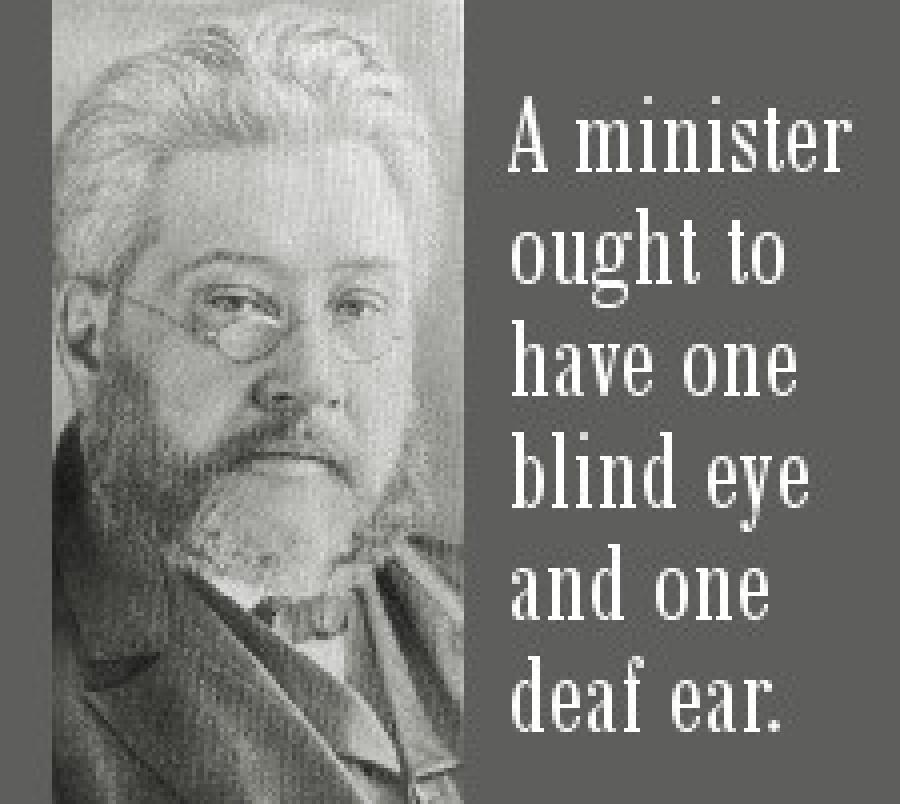

The Blind Eye and the Deaf Ear (Part 2)

Image

This post continues a lecture from C.H. Spurgeon’s Lectures to My Students (read the series so far).

I should recommend the use of the same faculty, or want of faculty, with regard to finance in the matter of your own salary.

There are some occasions, especially in raising a new church, when you may have no deacon who is qualified to manage that department, and, therefore, you may feel called upon to undertake it yourselves. In such a case you are not to be censured, you ought even to be commended. Many a time also the work would come to an end altogether if the preacher did not act as his own deacon, and find supplies both temporal and spiritual by his own exertions. To these exceptional cases I have nothing to say but that I admire the struggling worker and deeply sympathize with him, for he is overweighted, and is apt to be a less successful soldier for his Lord because he is entangled with the affairs of this life.

In churches which are well established, and afford a decent maintenance, the minister will do well to supervise all things, but interfere with nothing. If deacons cannot be trusted they ought not to be deacons at all, but if they are worthy of their office they are worthy of our confidence. I know that instances occur in which they are sadly incompetent and yet must be borne with, and in such a state of things the pastor must open the eye which otherwise would have remained blind.

Rather than the management of church funds should become a scandal we must resolutely interfere, but if there is no urgent call for us to do so we had better believe in the division of labor, and let deacons do their own work. We have the same right as other officers to deal with financial matters if we please, but it will be our wisdom as much as possible to let them alone, if others will manage them for us.

When the purse is bare, the wife sickly, and the children numerous, the preacher must speak if the church does not properly provide for him; but to be constantly bringing before the people requests for an increase of income is not wise. When a minister is poorly remunerated, and he feels that he is worth more, and that the church could give him more, he ought kindly, boldly, and firmly to communicate with the deacons first, and if they do not take it up he should then mention it to the brethren in a sensible, business-like way, not as craving a charity, but as putting it to their sense of honor, that “the laborer is worthy of his hire.”

Let him say outright what he thinks, for there is nothing to be ashamed of, but there would be much more cause for shame if he dishonored himself and the cause of God by plunging into debt: let him therefore speak to the point in a proper spirit to the proper persons, and there end the matter, and not resort to secret complaining. Faith in God should tone down our concern about temporalities, and enable us to practice what we preach, namely:

Take no thought, saying, What shall we eat? or, What shall we drink; or, Wherewithal shall we be clothed? for your heavenly Father knoweth that ye have need of all these things.

Some who have pretended to live by faith have had a very shrewd way of drawing out donations by turns of the indirect corkscrew, but you will either ask plainly, like men, or you will leave it to the Christian feeling of your people, and turn to the items and modes of church finance a blind eye and a deaf ear.

The blind eye and the deaf ear will come in exceedingly well in connection with the gossips of the place.

Every church, and, for the matter of that, every village and family, is plagued with certain Mrs. Grundys, who drink tea and talk vitriol. They are never quiet, but buzz around to the great annoyance of those who are devout and practical. No one needs to look far for perpetual motion, he has only to watch their tongues. At tea-meetings, Dorcas meetings, and other gatherings, they practice vivisection upon the characters of their neighbors, and of course they are eager to try their knives upon the minister, the minister’s wife, the minister’s children, the minister’s wife’s bonnet, the dress of the minister’s daughter, and how many new ribbons she has worn for the last six months, and so on ad infinitum.

There are also certain persons who are never so happy as when they are “grieved to the heart” to have to tell the minister that Mr. A. is a snake in the grass, that he is quite mistaken in thinking so well of Messrs. B and C., and that they have heard quite “promiscuously” that Mr. D. and his wife are badly matched. Then follows a long string about Mrs. E., who says that she and Mrs. F. overheard Mrs. G. say to Mrs. H. that Mrs. J. should say that Mr. K. and Miss L. were going to move from the chapel and hear Mr. M., and all because of what old N. said to young O. about that Miss P.

Never listen to such people. Do as Nelson did when he put his blind eye to the telescope and declared that he did not see the signal, and therefore would go on with the battle. Let the creatures buzz, and do not even hear them, unless indeed they buzz so much concerning one person that the matter threatens to be serious; then it will be well to bring them to book and talk in sober earnestness to them. Assure them that you are obliged to have facts definitely before you, that your memory is not very tenacious, that you have many things to think of, that you are always afraid of making any mistake in such matters, and that if they would be good enough to write down what they have to say the case would be more fully before you, and you could give more time to its consideration. Mrs. Grundy will not do that; she has a great objection to making clear and definite statements; she prefers talking at random.

I heartily wish that by any process we could put down gossip, but I suppose that it will never be done so long as the human race continues what it is, for James tells us that “every kind of beasts, and of birds, and of serpents, and of things in the sea, is tamed, and hath been tamed of mankind: but the tongue can no man tame; it is an unruly evil, full of deadly poison.”

What can’t be cured must be endured, and the best way of enduring it is not to listen to it. Over one of our old castles a former owner has inscribed these lines:

They say.

What do they say?

Let them say.

Thin-skinned persons should learn this motto by heart. The talk of the village is never worthy of notice, and you should never take any interest in it except to mourn over the malice and heartlessness of which it is too often the indicator. Mayow in his “Plain Preaching” very forcibly says,

If you were to see a woman killing a farmer’s ducks and geese, for the sake of having one of the feathers, you would see a person acting as we do when we speak evil of anyone, for the sake of the pleasure we feel in evil speaking. For the pleasure we feel is not worth a single feather, and the pain we give is often greater than a man feels at the loss of his property.

Insert a remark of this kind now and then in a sermon, when there is no special gossip abroad, and it may be of some benefit to the more sensible; I quite despair of the rest.

Above all, never join in tale-bearing yourself, and beg your wife to abstain from it also. Some men are too talkative by half, and remind me of the young man who was sent to Socrates to learn oratory. On being introduced to the philosopher he talked so incessantly that Socrates asked for double fees.

“Why charge me double,” said the young fellow.

“Because,” said the orator, “I must teach you two sciences: the one how to hold your tongue and the other how to speak.”

The first science is the more difficult, but aim at proficiency in it, or you will suffer greatly, and create trouble without end.

- 19 views

Spurgeon certainly addresses some things, the likes of which I’ve seen as well, but I’m not sure that the blind eye and the deaf ear are always the proper response today. Maybe it was in Victorian times—people would catch on that they were being ignored and change their ways—but I think today, gossip really ought to be confronted. So I understand his motivations, but disagree somewhat with his application.

Aspiring to be a stick in the mud.

Discussion