O Zion Haste

Image

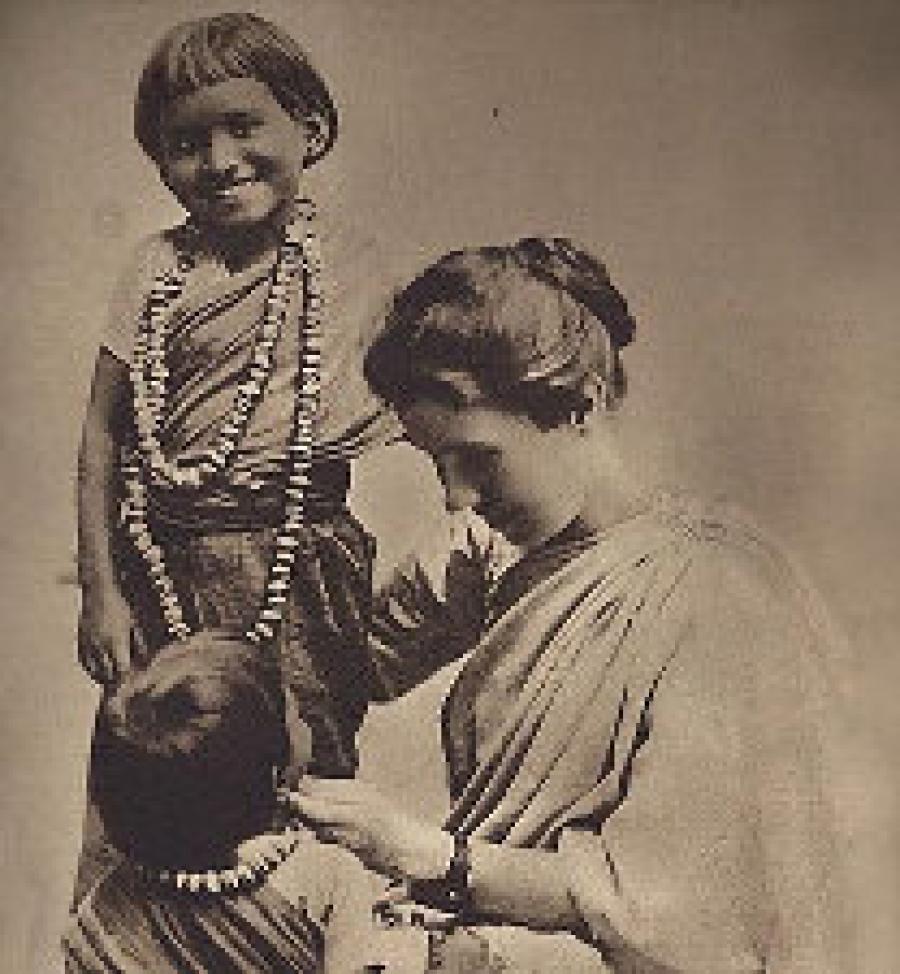

Amy Carmichael with children in India

One Sunday, when I was five, I walked into the sanctuary of our small, conservative church, and there, stretched across the back of the last pew, was the skin of an African python. Our speaker for the morning was a missionary from the Central African Republic, and by the end of the service, I was certain that my future included living in a hut, facing down autocratic tribal chiefs, establishing medical clinics and schools, and rescuing orphans from dark, pagan traditions.

I grew up in the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains in a region dotted by dilapidated family farms and former coal towns. We are the second poorest county in the state and the most exotic animal we ever saw was the occasional bear or mountain lion. But within the church I discovered the world.

I met women like Amy Carmichael and Mary Slessor and learned that the measure of womanhood was not your relationship status or professional accomplishments, but whether you lived your life in service of God and others. In elementary school, I knew the flags of over thirty nations—not because of the Olympics but because we hung them from the ceiling every year during our missions conference week. I became versed in Cold War politics when for two summers we sent our VBS nickels and dimes to the underground church in the Soviet Union.

The story of Christian missions is a complicated one. When I was young, it was all about adventure and holy passion and converting cannibals. As I grew older, I discovered that mission efforts often ran parallel to and sometimes intersected the darker story of western colonization. I read Achebe and Paton and Forster and had to face the reality that when David Livingston was taking the gospel to free souls in the interior of Africa, the United States was embroiled in a civil war to keep their cousins enslaved.

Until recently, sorting through the complicated picture of Christian missions has been more a question of presuppositions and sanitized history. And to some degree, it always will be; but thanks to sociologist Robert Woodberry, it might be getting a bit clearer. In the latest edition of Christianity Today, Andrea Palpant Dilley writes about Woodberry’s work to find a “significant statistical link” between democracy and Protestantism. And after years of detailed research, extensive travel, and with the help of some elaborate computer models, he has.

Woodberry’s research can be summed up by this claim:

Areas where Protestant missionaries had a significant presence in the past are on average more economically developed today, with comparatively better health, lower infant mortality, lower corruption, greater literacy, higher educational attainment (especially for women), and more robust membership in nongovernmental associations.

In a word, when I was learning about Amy Carmichael and Mary Slessor, I was learning about the greatest promoters of sustainable democracy.

If my childhood was shaped by the stories of missionaries and conversion, my adult life has been shaped by the stories of soldiers and violence. I was a newly-married 22-year-old on September 11, 2001, still naïve enough to believe that our response would be limited to fighting the Taliban in Afghanistan. But over the subsequent decade, our attempts to “bring democracy” to the Middle East have failed; and if this has taught us anything, it’s that we cannot win “hearts and minds” with guns and tanks. In fact, if Woodberry’s claims are correct, this is best accomplished through the gospel of peace.

But it’s even more startling than that.

According to Woodberry, the missionaries who had the most profound influence on developing democracies were “conversionary Protestants.” They were missionaries whose social work—the work of building schools and hospitals and advocating for the rights of the oppressed—was motivated directly by their evangelistic impulses. In other words, these missionaries did not go to the far-flung corners of the world in the name of social activism; they went to convert souls in the name of Jesus Christ and in the process, changed the world.

So my question is why? Why must conversion be a vital part of missiology in order to affect real and lasting social change?

I think the answer is wrapped up in what conversion is. True, gospel conversion is fundamentally about change. It changes how we understand God, ourselves, and each other. For people like David Livingstone and Amy Carmichael, the gospel so profoundly changed them that they ended up changing the world. Perhaps without even realizing it.

At the same time, Woodberry’s research also reminds us that the gospel is not simply about future flourishing. The gospel changes life here and now by reconciling us to God and each other. When the gospel teaches us to fight greed, violence, and apathy in our own hearts—when it teaches us that we are truly our brother’s keeper because God is ours—the gospel sets the foundation for societies that can flourish.

And if it isn’t doing this, you can be pretty sure it’s not the gospel.

More than anything Woodberry’s research confirms what the Scripture already teaches us. It confirms that where the Prince of Peace (Isa. 9:6) reigns, there is peace; where the Bread of Life (John 6:35) grows, hunger will not; where the Great Physician (John 5) is at work, disease and death flee. And ultimately, it confirms that when the Author of Life is allowed to write the story of our lives, we will finally be free to live in the abundant life (John 10:10) that He has promised.

handerson Bio

Hannah R. Anderson lives in Roanoke, VA where she spends her days mothering three small children, loving her husband, and scratching out odd moments to write. She blogs at Sometimes a Light and has recently published Made For More.

- 5 views

Hannah always makes me think and this essay is no exception.

It has me a bit conflicted though. On one hand it makes perfect sense to me that in any society where large numbers of people experience genuine conversion to Christ (and even larger numbers absorb Christian assumptions about all sorts of things) there would also be way-above-baseline level of the virtues of good citizenship. So, other things being equal, democracy would thrive there… along with lifestyles that are far less self-destructive than you would see in the general population.

And I’m all for that. Good is good, and more of it is always better than less. That’s almost what “good” means.

On the other hand, better earthly societies is not what the gospel is for or what we should necessarily expect it to do. As a non-postmillennialist, I see a sharp distinction between what the gospel does to human society and what Christ Himself does directly. It’s not the gospel that brings in the society we all long for. Rather, the gospel brings us to Christ and He Himself (without much help from us, judging from Rev.19) brings in the society we all long for, while we apparently just watch in awe.

I’m not in the “we’re brining in the kingdom” crowd, but also not in the “the gospel is of no temporal, practical use” crowd or the “there’s no point in improving people’s lives” crowd.

Views expressed are always my own and not my employer's, my church's, my family's, my neighbors', or my pets'. The house plants have authorized me to speak for them, however, and they always agree with me.

Eschatological paradigms are really significant to missiology—I don’t think people always recognize how their view of the future affects their work in the present. One thing the original piece didn’t investigate was the the influence of post-mil. theology on 19th and early 20th c. missions. There is a definite resurgence of a “social gospel” among millennial Christians. I don’t think they realize that it’s “same song, different verse” kind of stuff. Personally, I think a touch of social reform is unaviodable—the gospel changes who we are and how we act toward each other. Insert illustration about city-wide revivals and saloons closing. On the other hand, I do think there is a real danger (especially among progressives ) to minimize Christ’s eventual return as the only source of true and lasting societal peace.

Discussion